November / December 2024

ILLUSION

NEIL RABINOWITZ

Brothers John and Rob (at the helm) Wilkinson grew up sailing a Blanchard Senior knockabout in the mid-1950s. Now in their mid-70s, they recently acquired a derelict Senior, thoroughly restored it, and named it ILLUSION.

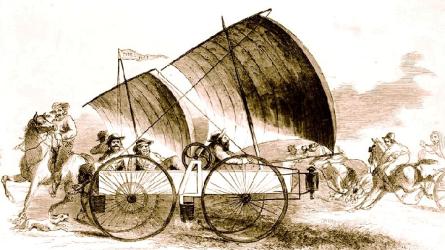

Classic boats do not necessarily spring from auspicious beginnings. As the boatbuilder Norman C. Blanchard of Seattle stated in his memoir, Knee-Deep in Shavings, one day in 1933 a group of Sunday strollers stopped into his Lake Union boatworks to ponder the 23' Star-class sailboats the shop had been building. Nice little boats, the browsers sniffed, but for that lofty price—$750—they would expect a cabin. This was in the doldrums of the Great Depression, and for comparison, a new Ford V8 coupe could be bought for as little $500. The strollers drifted off. Blanchard’s father and business partner, Norman J. Blanchard, thought for a few moments and said, “Dammit, let’s build a cheap sailboat with a cabin on it.”

And that’s what they did—though the modifier “cheap” needs to be taken apart and inspected from several angles.

Throughout the first six decades of the 20th century, Seattle’s vigorous boatbuilding industry, clustered in a ring around Lake Union in the heart of the city, cranked out several wooden production boats that have become treasured for both their practicality and surprising beauty—and durability (see “The Dream Boats of Seattle,” WB No. 277). It was an era when “cheap” had a different resonance than it does today: boats such as these wouldn’t be around nearly a century later if they had been built expediently and flimsily.

Norm J., a ninth-grade dropout who began learning boatbuilding as a teenaged apprentice, had opened his own shop in 1919 and was immediately successful. His first commission was a 62' schooner. Impressively large motoryachts followed, some over 100' long. His son, who’d turned professional as a teenager—with a $10 commission for a model boat—became a partner in the company full-time after his high-school graduation in 1931. Times were hard, though. Most of the largeboat commissions had evaporated. The Blanchards lost their family home to foreclosure. The small boats they built helped keep the shop doors open, but they didn’t contribute much to the bottom line. In 1974, Norm C. told an interviewer that the company had built 80 percent of their Senior Knockabouts to order; the rest was built as filler to keep employees busy between larger orders. The shop whisked them through production as deftly as possible for a carvel-planked boat. They had a standard mold to bend frames around, and they are believed to have had templates to mark planks for bandsawing. “We would start framing a Knockabout on Monday and it would be off the mold by Friday,” Norm C. told another journalist in 2000. Yet, he claimed, they never managed more than 3 percent profit on the Seniors.

To read the rest of this article:

Click the button below to log into your Digital Issue Access account.

No digital access? Subscribe or upgrade to a WoodenBoat Digital Subscription and finish reading this article as well as every article we have published for the past 50-years.

ACCESS TO EXPERIENCE

Subscribe Today

1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION (6 ISSUES)

PLUS ACCESS TO MORE THAN 300 DIGITAL BACK ISSUES

DIGITAL $29.00

PRINT+DIGITAL $42.95

Subscribe

To read articles from previous issues, you can purchase the issue at The WoodenBoat Store link below.

Purchase this issue from

Purchase this issue from