Thrill and Tradition

In the mid-to-late 1980s, I was passionate about windsurfing. I kept a board in the back of my pickup truck and, when the conditions were ideal, I would drop everything to go sailing. What, you might ask, was the attraction of it?

Someone once said to me that windsurfing is the purest form of sailing. Upon decades of reflection, I couldn’t agree more. There’s no rudder; rather, there’s just the mast articulating on a universal joint to steer the board. A sailor is literally holding the center of effort in their hands when windsurfing, and the center of lateral resistance is right there below the feet. These two terms move solidly from the theoretical to the practical when windsurfing: rake the mast aft, and the board heads up; rake it forward, and the board bears away. It’s rig-balance personified; weather helm has consequences beyond a heavy tiller. The sport certainly made me a better sailor.

I don’t know why I drifted away from windsurfing, but the sport’s popularity certainly crashed after a while. I think it had something to do with gear intensity: To really remain engaged in windsurfing and keep up with fellow sailors, one eventually needed—or at least craved—a “quiver” of sails and boards for various conditions. I recall cars stuffed with sails, wetsuits, and other gear. The purity of the learning days—of one sail, one board, and one sailor—bled out of it.

Somehow, through genetic predisposition or osmosis, my son Linus recently developed a passion for windsurfing, and resolved to spend a portion of his summer earnings on a board. It turns out there are some real bargains out there due to leftovers from the days of gear-stuffed cars. Together we found a board, for which Linus paid a hundred bucks cash, and he let me take my first ride in 35 years. My balance and strength were rusty, but the muscle memory remained. And I was reminded of a realization I’d had many years ago when dabbling in Laser-class dinghies: board-style boats such as the Laser offer much of the acceleration-induced thrill of a windsurfer, but a person of modest abilities doesn’t fall overboard every few minutes or get exhausted from uphauling the sail and making wobbly tacks. Maybe a Laser was where it was at.

For years, I’ve nursed along a dream of collaborating with a designer to develop a home-buildable, wooden Laser-type boat driven by an off-the-shelf rig. I even called Bruce Kirby, the Laser’s designer, to discuss the idea. It would be called the Lignum Laser, I told him. Bruce was cordial in entertaining the concept but, understandably, didn’t want to dilute the success of the Laser given that, with nearly a quarter million of them sailing in 140 countries, it is the most popular one-design in the world. The idea has nagged at me and evolved over the years. Maybe it could be a two-person boat, or for a single adult who’s outgrown a Laser or needs a little more boom clearance or room to sprawl.

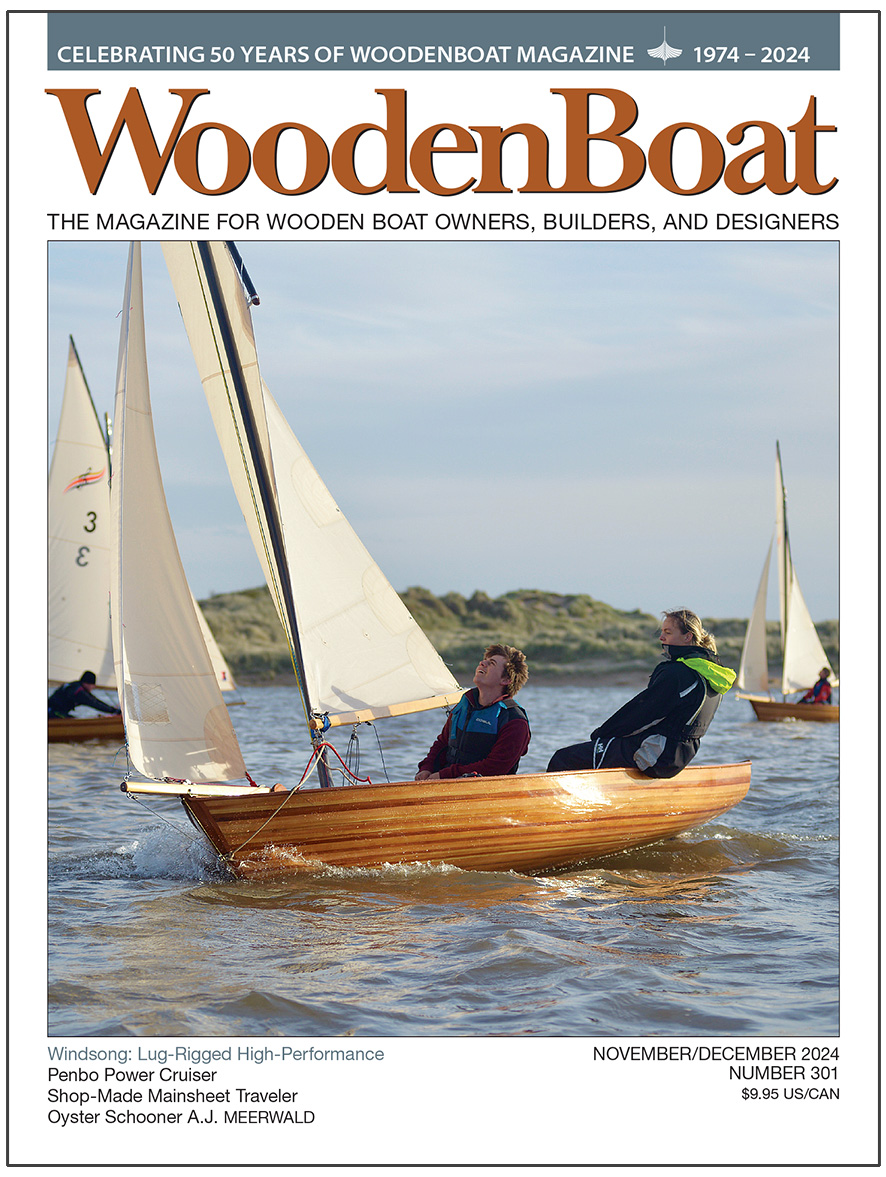

I finally had an “aha” moment recently when Nic Compton pitched his article on the Windsong-class dinghy that appears on the cover of this issue. For me, it checks all of the boxes: It’s strip-planked and sheathed in fiberglass—a tough, stiff, lightweight, and straightforward construction method ideal for such a boat. As its designer, John Owles, says in Nic’s article beginning on page 38, “I just whittled and whittled and whittled until I reduced the hull resistance to as low as possible.” It planes at 12 knots in 20 knots of breeze. It appears to be thrilling yet forgiving, not requiring the acrobatics of a trapeze or the instability of a 16-Foot skiff. It’s beautiful. It’s lug-rigged. And it’s wooden.

Needless to say, I’m captivated by the Windsong. It rekindles, for me, something from those thrilling days of windsurfing and Laser sailing while adhering to my enduring draw to good wooden boats grounded in tradition.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine