The Parallel Passions of Oliver Berking

A visit to Germany’s premier classic wooden boat yard

A visit to Germany’s premier classic wooden boat yard

ROBBE & BERKING CLASSICS

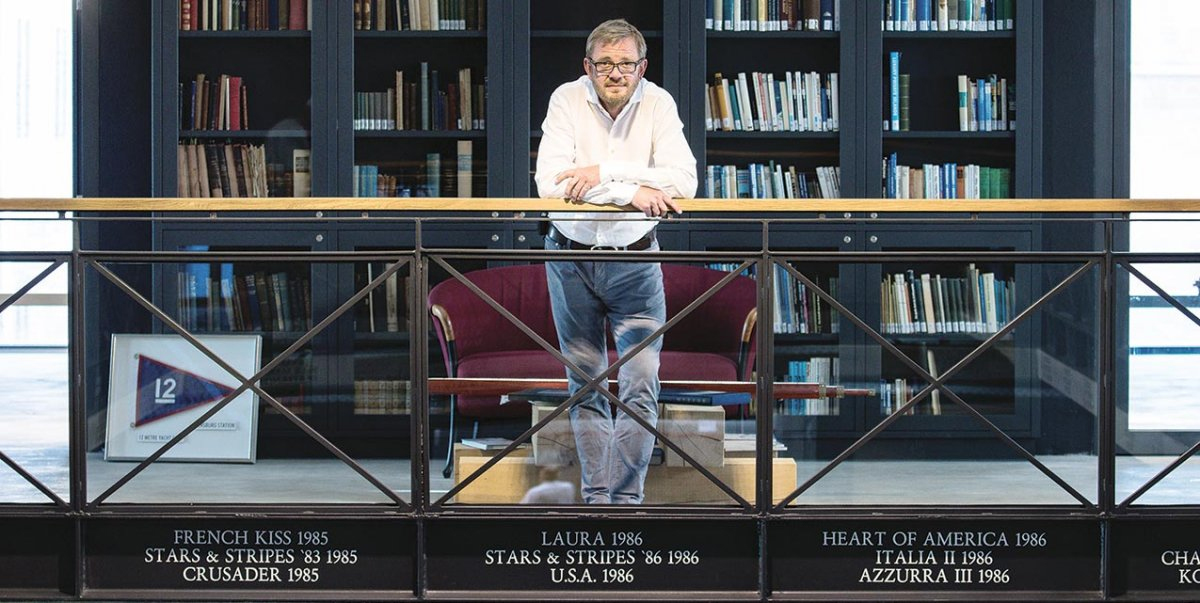

Above—Oliver Berking, who represents the fifth generation to operate the family-owned fine silver business Robbe & Berking Silver of Flensburg, Germany, has a parallel passion for classic wooden yachts. He has turned this passion into another business, Robbe & Berking Classics, through which he operates a yacht yard, an exhibition hall, and a magazine. Behind him in this photograph is Robbe & Berking’s 9,600-volume library of yachting literature.

“…[I]t is an interesting biological fact that all of us have in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and, therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea—whether it is to sail or to watch it—we are going back from whence we came.”

at the dinner for the 1962 AMERICA’s Cup Crews

On September 18, 1962, GRETEL, the first-ever Australian 12-Meter-class sloop, beat the AMERICA’s Cup defender WEATHERLY by a margin of 47 seconds. It was the second race of the Cup’s final series, and the victory sent a shock wave through the sailing world and touched off gleeful pandemonium Down Under. Could this be the first year that the Cup would be wrested away from its American grip since its inception in 1851?

Alas for Australia, it was not to be. The Philip Rhodes–designed 12-Meter WEATHERLY went on to win the next three races, and the prize, in front of a dense spectator fleet off Newport, Rhode Island. Those 1962 AMERICA’s Cup races were significant for many reasons. Among them was the fact that President John F. Kennedy was there, observing the first race from the deck of the Navy destroyer named for his older brother, USS JOSEPH P. KENNEDY, JR. Also noteworthy was the fact that GRETEL’s sole victory signaled an ascendant Australian sailing program that would flower two decades later, in 1983, when the United States finally lost the auld mug to the winged-keel phenom AUSTRALIA II. Another important event that coincided with that contest went virtually unnoticed at the time, but eventually it was vital to the legacy of the 12-Meter fleet: on the day of GRETEL’s lone victory, 3,600 miles away from Newport, a baby named Oliver Berking was born into the fifth generation of a family of silver artisans in Flensburg, Germany.

ROBBE & BERKING CLASSICS

The 12-Meter-class sloop SPHINX rolls out of a Robbe & Berking storage shed in the spring of 2009. She was relaunched in 2008 after a meticulous two-year restoration that assembled the talent, tools, and space that would become Robbe & Berking Classics.

Today, 55-year-old Oliver runs the 143-year-old family silver business, called Robbe & Berking, a time-consuming endeavor that requires extreme focus on detail, raw material, and market conditions. But despite this demand on his attention, Oliver has an unquenchable parallel passion for classic yachts, and particularly classic 12-Meter yachts. Tapping this passion, he has founded another business that builds, restores, and maintains some of the finest yachts in northern Europe. The newer company bears much of the same branding as the fine silver company, including the name: it is called Robbe & Berking Classics, and it projects an image of luxury and exclusivity while also being open to whomever walks through its doors. It has built and restored 6-, 8-, and 12-Meter-class yachts, among other boats, and its complex of buildings occupies a portion of a commercial wharf opposite Flensburg’s revered historic harbor (see sidebar). The yacht business is more than a boatyard: It includes a hall that maintains a rotating series of three to four temporary yachting-themed exhibitions per year. It houses a classic-yacht brokerage called Baum & Konig and a 9,600-volume library of yachting books. It publishes a highly produced magazine called Goose. And it rents space to several marine businesses and a popular fine Italian restaurant, both of which guarantee a steady flow of well-heeled visitors.

Oliver carries the significance of his birthday like a calling card. “I was born on the day GRETEL won over WEATHERLY,” he told me as we toured the Robbe & Berking Classics grounds upon my arrival in Flensburg in late April this year. A Riva Aquarama, that most rarefied model of classic Italian wooden speedboat, stood nobly in the exhibition hall surrounded by a collection of vintage Mercedes-Benz automobiles displayed there by a local dealer. In the adjacent shop, the recently arrived 72′ Sparkman & Stephens yawl BARUNA was partially disassembled in mid-restoration for an American owner. In another room was a fleet of 6-Meters, many of which were built by Robbe & Berking Classics. Outside of the main building, at the edge of the parking area, stood, incongruously, a life-sized, multicolored fiberglass-over-foam statue of a rhinoceros, to which we shall return.

ROBBE & BERKING CLASSICS

A crowd gathers in the yard’s workshop for a party during the Robbe & Berking Sterling Cup in 2013. Robbe & Berking hosts an ongoing series of such events. On display here is the yard-built replica of the Sparkman & Stephens–designed 6-Meter-class sloop BUZZY III—the original of which is also under the care of Robbe & Berking, and now named GREAT DANE.

Opposite the rhinoceros, standing sentry over the entire operation, was the tired hulk of that pioneering Australian 12-Meter, GRETEL, an apparition from 1962 awaiting a savior to move her into the nearby shop and put her right.

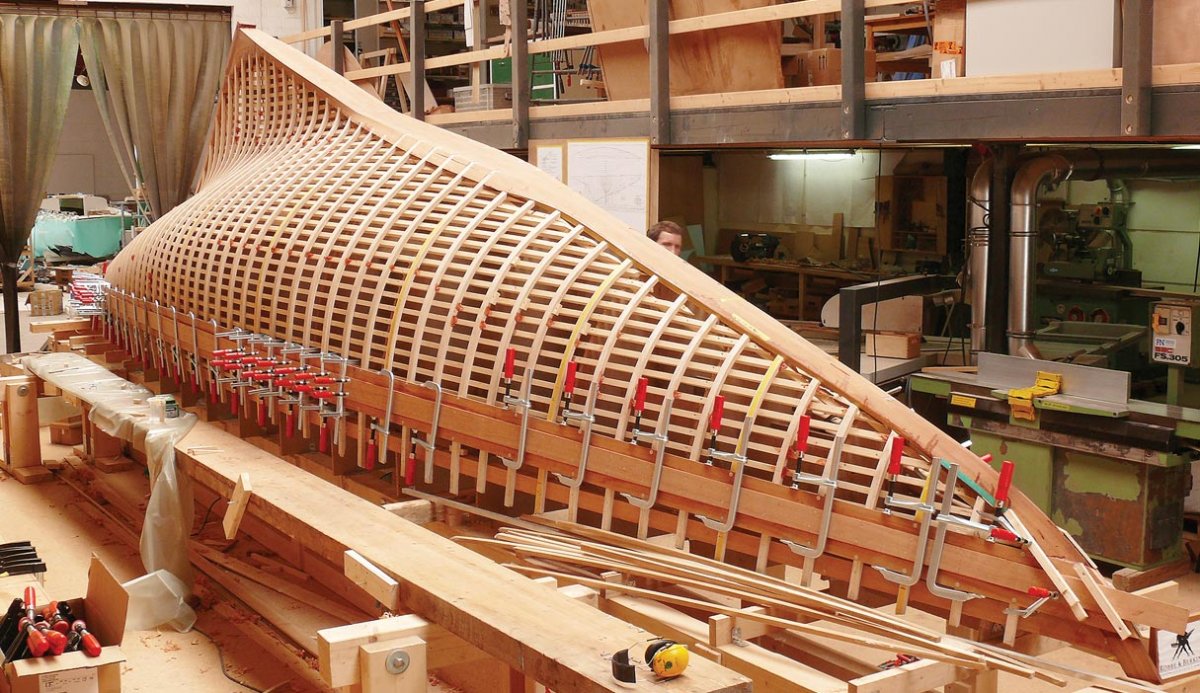

The seeds of Robbe & Berking Classics were sown in 2005 when the German Navy decided to sell a pair of classic 12-Meters, OSTWIND and WESTWIND, that it kept for training purposes for 50 years at a base near Flensburg. These boats, said Oliver, are “to me the most beautiful 12-Meters afloat. A lot of us in Flensburg cried” at the thought of them leaving the incomparable sailing waters of Flensburg Fjord. So Oliver led the formation of a syndicate—a “bidding group,” he called it—that bought OSTWIND, which was launched in 1939, and gave her back her original name, SPHINX. By 2006, the group decided to restore the boat to its original condition. “I didn’t have a yard,” he recalls. “I didn’t know boatbuilding.”

What Oliver did know, and what he has staked his yachting venture on, is that there is a small but exuberant market for rare, finely made objects. He knows this from his silver business, which hand-makes, among many other objects—including egg cups, cocktail shakers, and candelabras—spoons that go through a 50-step production process and cost $210 apiece. A functional knockoff might cost 30 cents, and yet these exquisite Robbe & Berking originals continue to sell, at a steady drip, to clients all over the globe. Five-star hotels and restaurants worldwide set their tables with Robbe & Berking flatware. The company equipped the Kremlin with a silver service 15 years ago. These sales are based on an emotional response to subtle, hand-crafted beauty. “You have to hit the hearts of the people,” Oliver said.

Still, he recalls that at the beginning of the OSTWIND project, “We were afraid. Articles in magazines and local rumors said that these crazy boys from Flensburg…if they start taking that boat apart, they will destroy it.” The syndicate, however, knew its limitations and potential, and hired six or seven competent shipwrights for the job. The sensitively restored SPHINX emerged from the shop in 2008, to critical acclaim. And then there was an empty shop, an idle crew, machinery and tools, and an ascending reputation. Oliver decided to keep the operation going, and to solicit more business for it.

ROBBE & BERKING CLASSICS

In 2011, Robbe & Berking launched this replica of the Sparkman & Stephens 6-Meter NIRVANA, the original of which was built by Abeking & Rasmussen in 1939 and destroyed by fire 20 years later.

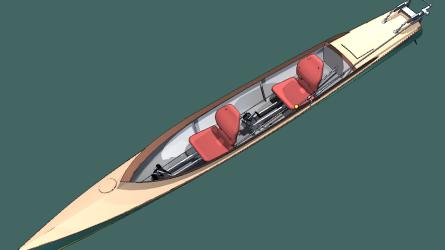

His father was seeking a new rowboat at about that time, and the yard built him a bright-finished custom 14′ mahogany one. That was Hull No. 1 of Robbe & Berking Classics—a humble project that primed the pump, so to speak. There followed a medley of historic reproductions, new designs, and restorations. One of them was a pair of 6-Meters built in anticipation of the class’s world championship in 2013, which Robbe & Berking would host in cooperation with the Flensburg Sailing Club. Then came a 50′ modern wooden cruising sloop, cold-molded and vacuum-bagged, to a design by the German naval architect Georg Nisen. Around the same time, the yard speculated on the construction of a 30′ powerboat of its own design inspired by the American commuter boats that ran wealthy financiers to work on Long Island Sound in the 1920s and ’30s. A reconstruction of the Sparkman & Stephens—designed 6-Meter NIRVANA followed that, and then came the yard’s pièce de résistance: a new 12-Meter.

ROBBE & BERKING CLASSICS

BARUNA, a legendary Sparkman & Stephens ocean racer from California, was recently shipped to Flensburg for a structural overhaul by Robbe & Berking. This is how she appeared in early spring this year. The temporary longitudinal bracing on her outer hull is meant to withstand the forces of reframing. She’s also receiving a backbone assembly, deck, and coach roof.

SIESTA, the new 12-Meter, was under construction during my first visit to Robbe & Berking, which was in February 2014. The yacht was launched and sailing when I returned there earlier this year. She is design No. 434 of the Norwegian master Johan Anker (see WB No. 239)—and one of his last, for Anker died a year after completing the plans for this yacht in 1939. But she was never built, because World War II halted the project, and the postwar 12-Meter Rule made her obsolete, in contemporary terms. But over the course of 75 years, she aged into the status of classic.

The SIESTA project came to Robbe & Berking because of the yard’s consistent and increasing service to the 12-Meter fleet, and to Meter-boats in general, since even before its founding. Oliver’s passion for these boats predates the SPHINX project. In 2001, Robbe & Berking Silver had hosted the 5.5-Meter World Championship. There followed, under the aegis of Robbe & Berking Classics, similar events for the 6- and 8-Meter classes, as well as for the 22-Square Meters. In 2011, Robbe & Berking Classics hosted the 12-Meter World Championship, drawing 10 boats, and in 2015 it hosted the European 12-Meter Championship, which drew a whopping 14 boats. “Never before have so many 12s been together in one harbor,” Oliver said.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

Robbe & Berking is committed to classic powerboats, too. The yard designed and built this 30’ diminutive commuter-style launch on speculation, but has kept it in its fleet as a regatta tender and company yacht.

His ambition has not been to simply create a shipyard. He clearly loves his native Flensburg region, and sees it as a world-class yachting destination. Flensburg Fjord is, indeed, blessed with a reliably steady breeze, light currents, minimal obstructions, and unfettered natural beauty. “My dream,” he said, “is that a sailor from Milan…who is not a poor man…says to his wife, ‘Honey, we have to go to Flensburg and enjoy its magnificent restaurant, view, and harbor.’ So they go, and then he returns home and tells his friends on Monday morning, ‘You have to go to Flensburg once in your life!’”

To this end, Oliver built the exhibition hall—a tastefully designed and rendered space that would befit any maritime museum or high-end art gallery. Its doors are open to the public, and a visitor is greeted at a reception desk that gives way to a central space with a soaring vaulted ceiling and a second story rimmed by a balcony hallway. In the edge of that balcony, etched in concrete, is the name of every 12-Meter built to date. The hallway itself is lined with books, approximately 9,600 volumes, which Oliver estimates to be the largest yachting library in the world. If a visitor takes a few steps beyond that central vaulted ceiling, he arrives at a massive sliding door which opens into the spacious, well lighted, and meticulously organized boatbuilding shop.

ROBBE & BERKING CLASSICS

The Yachting Heritage Center, shown here during a visit by a group of Mercedes-Benz aficionados, is the heart of Robbe & Berking Classics. The wing to the right is the workshop. The structure to the left was recently added to house the exhibition hall, office space, and a restaurant. Below—Oliver Berking sets up a photograph for the current exhibition: JFK, The Sailing President.

BARUNA, the 72′ yawl that’s currently taking up a portion of the shop, was launched by the Quincy Adams Yacht Yard in Massachusetts in 1938 and won the Bermuda Race that year, with her deisgner, Olin Stephens, navigating, before going to her longtime home waters of California. She had arrived in Flensburg while I was home in Maine planning my trip; Martin Schulz, who is the project manager for Robbe & Berking, texted me several photos of the yacht upon her arrival. She had come in from Denmark on her own bottom, tired and wet, and was immediately hauled and moved into the shop.

When I encountered her in person, her garboards, sheerstrakes, house, and deck had been removed, and the crew was milling stock for her new laminated-mahogany keel. New laminated frames were progressing at the same time. The shop aims to have the keel, stem, and frames replaced by autumn, when she’ll then go to another shop for a new Andre Hoek–designed interior. Overseeing the project is Sønke Stich, the shop foreman, a German boatbuilder who once ran his own shop in Norway.

Next to BARUNA lay neat stacks of long, wide mahogany boards awaiting milling and laminating to become the new keel. And nearby, a new mast for the 1918 12-Meter THEA was taking shape. That boat was too tender under her old, taller rig, and the new mast, of flawless Sitka spruce, is intended to cure this. BARUNA occupies only a fraction of this workshop, which is flooded with natural light coming in through a 25'-tall bank of windows.

INA STEINHUSEN

Johan Anker designed the 12-Meter SIESTA in 1939, but she was never built due to the exigencies of World War II. Robbe & Berking Classics resurrected the design several years ago, and launched the new yacht, seen here on trials, in 2015.

Opposite the building that houses the Yachting Heritage Center and workshop is a new, freestanding shed with humidity and temperature control, originally meant to be a showroom of sorts for the brokerage boats—“a humidor for yachts,” Oliver called it. But that vision has been modified to serve the growing storage business. The yard currently stores eleven 12-Meters, and had launched seven of them the week before I arrived. Most of them are wooden, but one is the fiberglass-hulled KIWI MAGIC, the first New Zealand 12-Meter, which attempted to win the AMERICA’s Cup from the Australians in 1987 after they had finally won it four years before. She is the first “modern” 12-Meter in the Robbe & Berking storage fleet, and Oliver anticipates that there will be more.

“I think you will always find some crazy boys or girls who want them,” Oliver said of the 12-Meters and other classic yachts he and his crew build, restore, and maintain, “but you have to search for the owners all over the world.” The Brokerage, Baum & Konig, has given him that reach. Its listings are a melting pot of classic European and American designers, and include names such as Mylne, Anker, Sparkman & Stephens, Herreshoff, Reimers, Camper & Nicholson, and Laurin. Oliver recalled that he wasn’t exactly seeking to enter the brokerage business when he acquired Baum & Konig, but its principal, Peter Konig, was moving on to other things, and he made Oliver an offer he couldn’t refuse. It has turned out to be a perfect complement to the existing business. “The yard and the brokerage have to know the same things,” Oliver said. “They must know what boat an owner has…and what he aspires to.”

As Oliver and I toured the buildings of Robbe & Berking Classics, three gentlemen walked in off the street and engaged him in friendly conversation. They were retired German navy officers. “Can you give me ten minutes?” Oliver asked, interrupting our conversation.

“Of course,” I said.

And he was off, with a spring in his step, to begin the tour all over again. I fixed myself an espresso in the on-site, self-serve café, which is furnished with high-top tables of rough-sawn elm, a retro green refrigerator behind the bar, and a vase of tree branches pushing early season leaves into the bright, cheery space. Oliver soon returned, aglow. “They fell in love, and I fell in love with them,” he said. The trio had sailed in the 12-Meters OSTWIND and WESTWIND in their cadet days.

ULF SOMMERWERCK

The fleet of 12-Meters charges down Flensburg Fjord during the Robbe & Berking Sterling Cup races, summer 2016.

We next ascended the stairs to the second-floor library. Upon reaching the top step, Oliver turned and faced me, and gestured toward the elevator opposite the stairwell, and then said, “It is all about little girls and boys like you and me staring at beautiful boats on the horizon.” He then pushed the button to open the door, and adorning the back wall of the elevator compartment was a life-sized vintage photograph of two little girls at the seashore, sitting on the gunwale of a lapstrake rowboat. One clutched a pair of teddy bears, while the other stared purposefully seaward through a brass telescope. It’s a powerful image that suggests the power of the place: in just a few short years, the Yachting Heritage Center has become a node where threads of yachting history intersect—where aging sailors reconnect with their former ships; where young sailors discover their ancestry.

Around the corner was the library. Oliver purchased it intact from a collector named Volker Christmann. He recalls, “There was a day when his wife said, ‘the books or me.’” One condition of the sale was that the books be shown to the public. They are under lock and key in purpose-built glass-fronted cases, but easily viewed and available for research. An iPad, encased in wood, sits at a study desk, and contains the card catalog.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

The rhinoceros, by the German artist Hans-Ruprecht Leiss, welcomes visitors to the Yachting Heritage Center.

On the same floor as the library is the Italian restaurant. It seats 200 diners twice per day, for a daily average of 400 guests walking through the Yachting Heritage Center. A precious few of these people are potential customers. “I want everyone who comes in to know that this is a place they can buy a boat,” says Oliver—“from the brokerage, or new.” While most of them are not yachtsmen, most are captivated by the Center’s ambience and rotating exhibitions.

The current exhibition is called JFK, The Sailing President. It is a collection of 40 photographs on loan from the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, summarizing the yachting endeavors of the president from his childhood through his final days. Nearby, a continuously looping film rotates through Kennedy’s viewing of the 1962 AMERICA’s Cup, his arrival in Berlin, and his famous “Eich bin ein Berliner” speech. It is a stirring display, and it would have been all the more so had Oliver been able to pull off the purchase, shipping from New England, and display of a Wianno Senior—a sistership to the Kennedy boat VICTURA, which is now at the Kennedy Library. Oliver has made such purchases in the past. He acquired GRETEL from Italy in hopes of attracting a new owner, and in 2009 he pulled the sodden hulk of the 12-Meter JENETTA out of a western Canadian Lake, in pieces, in hopes of restoring her. Neither of those projects has yet come to fruition. Perhaps having learned from these experiences, he decided, in the final analysis, that procuring an actual Wianno was too risky an investment for the Kennedy exhibit.

That seems to be the Oliver Berking modus operandi: to push the limits of the dream in his imagination, and then dial it back to the fantastically feasible.

MATTHEW P. MURPHY

Oliver Berking visits the final inspection point of the 50-step process of making a Robbe & Berking silver spoon. “The silver. The boats. It is the same story,” says Oliver.

Oliver’s dreamscape of possibility is perhaps best represented by the magazine, Goose. It’s a high-quality effort, as much a book as quarterly magazine. Upon viewing it for the first time, however, I did not understand the title. It now makes perfect sense to me.

“I was thinking a lot about 6-Meters,” Oliver said of the time of the founding of the magazine in September 2011. “And the best, the fastest one, was Olin Stephens’s GOOSE.” That, however, would be too obvious a reason for the title; the 6-Meter GOOSE was but a gateway to its more subtle symbolism. In a classic Swedish children’s tale by Selma Lagerlöf, a boy named Nils Holgersson rides atop a goose on an adventure that gives him a grand view of the wonders of the Swedish countryside. Goose magazine is Oliver Berking’s personal goose. From it, he said, and with the expert editing of Detlev Jens, he “observes the shores and the wonders of the world.”

Such metaphor and symbolism weave through the elegance of this place. GRETEL…the Kennedy mystique…the photograph in the elevator…the rhinoceros guarding the entrance. The rhinoceros is the work of a German artist named Hans Ruprecht Leiss, who is a friend of Oliver’s, and it touches upon the theme of the 1983 film And the Ship Sails On, by the Italian director Federico Fellini.

In the film, a group of people gather in 1914 aboard a cruise ship to mourn the death of an opera singer. During the social proceedings, a horrible smell emerges from the hold, which turns out to be a neglected rhinoceros who is subsequently fed, watered, and given a clean space. The cruise then continues until an encounter with a Serbian gunboat, which sinks the cruise ship. In the final scene, the protagonist, Orlando, is in a lifeboat with the rhinoceros, and the camera then pans to reveal the behind-the scenes workings of the film’s belle époque luxury—a giant hydraulic jack that moved the ship; the plastic ocean; the legions of technicians behind the scenes. It’s like a massive door in a luxurious yachting exhibition hall being rolled open to reveal a crew of craftsmen laboring to create exquisite luxury in a working boatshop.

The film’s German title is Schiff der Träume, which means “Ship of Dreams.” “That is what we do here,” said Oliver. “We build boats of dreams.”

“Everything I do,” he said, “is from times far away. You don’t need it anymore. You don’t need a wooden boat. You don’t need a silver spoon. You don’t need a magazine printed on paper.” These things are splendid luxuries, and at the Yachting Heritage Center you can glimpse the soul of the craft. You can distinguish the sterling from the silver-plated.

Oliver gave me a tour of the silver company the following day. It is now the largest silver manufacturer in the world, but like the business of wooden boats, the overall industry is a faded image of what it was. There were once three such companies in Hamburg employing 1,000 people each. Now there is only Robbe & Berking, in Flensburg, with 172 employees.

It is located in a distinguished-looking brick building on the outskirts of Flensburg. This was dairyland when the building was new in 1957; it is now populated by car dealerships. We walked through all 50 steps in the making of a spoon, which involved much handwork—cutting, grinding, polishing, detailing, more polishing—and two quality-control points to guard against expensive labor being expended on a piece that was flawed early on. At the end of the tour came a promotional film for Robbe & Berking—the silver company and the yacht company combined—showing beautiful, well-dressed people sailing and motoring in beautiful boats, picnicking ashore on an Island in Flensburg Fjord, eating eggs from silver cups. Children gamboled in pastel shirts and dresses while their parents sipped sparkling wine from silver goblets. After the film ended and the room was silent for a moment, Oliver said, with slightly ironic grin, “And that is how we live every day.” Which is not true.

What is true is that Oliver and his wife enjoyed their honeymoon cruise in the spartan accommodations of a 25′ Folkboat, and he gets up every morning to create a product. That product happens to be rare, handmade objects for a very small market. “It is manufacturing in the purest sense of the word,” he said. “The silver. The boats. It is the same story.”

Regarding the emotional impulse behind the creation of the Yachting Heritage Center and the shipyard, Martin Schulz observed, “I don’t think he would have done this if he had not grown up in Flensburg—if his family business had been in the big city. Here, he would have seen the ferries and the steamers going up and down Flensburg Fjord. It’s impossible to miss.”

After my visit to Flensburg, I made a short trip to Hamburg, the big city, to visit my old friend Taco Rison. He is a Dutch expat who has spent decades in the classic-yacht restoration business, and seems to know everybody in the northern European wooden boat scene. He’s been living in Germany for about 15 years. I told him a bit about my visit with Robbe & Berking.

“They do the best work in Germany,” he said succinctly.

“The best wooden boat work in all of Germany?” I asked him, hoping for an elaborate explanation.

“No doubt about it,” he said, nodding, and without a hint of hesitation.

Matthew P. Murphy is editor of WoodenBoat.

TAFF/BENJAMIN

Flensburg’s Historic Harbor Flensburg’s Historic Harbor Flensburg is a small, compact city of 89,000 located on the German border with Denmark in the state of Schleswig-Holstein. It was left largely unscathed by the widespread Allied bombing campaign of World War II, and so its historic edifices are unusually intact for a German city. While it is known for its beer, rum, and trading history, its crown jewel is its beautifully protected historic harbor, the Museumshafen Flensburg, which provides year-round berth space for classic working boats and vessels of regional significance.

The Museumswerft Flensburg, an interpretive center, is located across the harbor from the Robbe & Berking Yachting Heritage Center. It operates a working shipyard, conducts seminars, publishes a newsletter, and hosts events.

The most popular annual gathering is the Flensburg Rum Regatta, which each May attracts a fleet of historic working vessels from northern Europe for spirited racing.

As Oliver Berking suggests in the main text, the city is a compelling destination for the wooden-boat minded, whether they lean toward yachts or working vessels. —MPM

For more information, visit https://museumshafen-flensburg.de