WANDERER III

A half-century on longitude 96° W

A half-century on longitude 96° W

WANDERER III charges along in the notorious “Furious Fifties” region of the South Atlantic in 2011 en route from South Georgia to Tristan de Cunha. The rugged 30′ Laurent Giles-designed sloop has sailed more than 300,000 miles in her 65 years and is still going strong..

I can still see myself standing dumbfounded in Papeete’s tiny harbormaster’s office in 1991, where in the pre-Internet days one used to pick up postal mail. A copy of WoodenBoat No. 101, with a cover shot of WANDERER III’s interior, had just arrived.

In Tahiti’s numbing heat, I barely recalled even having written an article two years earlier while anchored near the magazine’s offices. The cover image, however, was a complete mystery: it was credited to me, but I had never seen it before. Eventually it dawned on me that I had sent off a roll of undeveloped film from the Caribbean.

WANDERER III, a Laurent Giles–designed 30′ sloop, had been commissioned by Eric and Susan Hiscock, who made their first circumnavigation in her in 1952–55. Their subsequent writing and photography had inspired a whole generation of sailors to get out there and sail far. The boat, Eric, and Susan had planted the seed for all of us who followed. Now, a decade into owning and sailing this legendary boat, my first article in English saw WANDERER III not only revitalized on the oceans, but also on the seascape of written words.

That early article focused mainly on repairs I had done in Denmark in the early 1980s to address problems created by the once-common English practice of connecting wrought-iron floors, via copper rivets, to a copper-sheathed hull. With this mix of metals immersed in warm, salty, tropical waters, WANDERER III had been a virtual battery.

Twelve years later, in another WoodenBoat article (WB No. 182), I dwelt upon the same legacy. During a more extensive second restoration, this time in New Zealand, I had reframed and refastened her, and replaced all remaining iron with bronze.

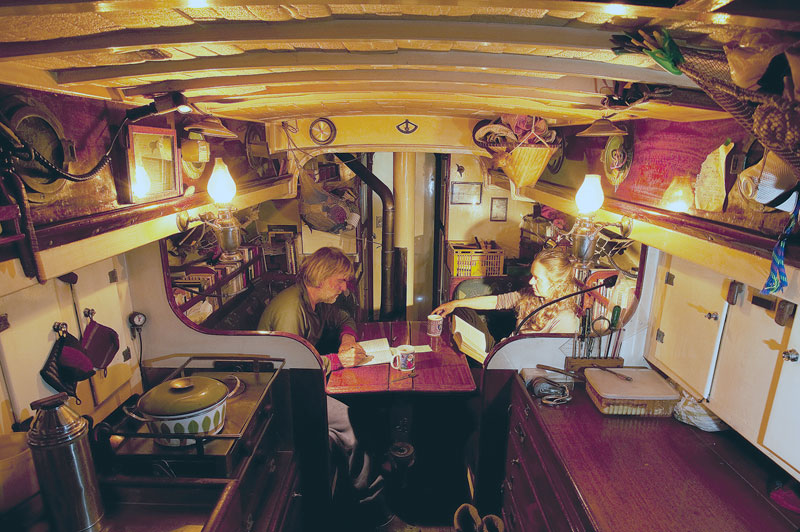

Thies Matzen and Kicki Ericson enjoy time below deck on a winter’s day in South Georgia. This wide-angle view gives the impression of space, but the cabin is, in fact, small yet cozy. It’s very much as it was in the days of the Hiscocks, but is now kept warm by a wood-burning stove rather than tropical airs.

But this won’t be another piece on the subject of repairs. Instead, this will be about what she was built for, what she does best: sailing, being pelagic, remaining out there. She is now 65 years old and few yachts, if any, have made more distant or varied voyages than she has. On two separate occasions she received the prestigious Blue Water Medal—the only yacht twice recognized for voyaging. Her first such commendation came in 1955, with Eric and Susan; the later one was with us, in 2011.

She is not the best, the fastest, the most comfortable, or even that ever-elusive “ideal” boat. Yet there is something that has captivated all of her three blue-water owners—Eric and Susan; Gisel Ahlers and his partner, Chantal Jourdan; and my wife Kicki Ericson and me—to take care of her and sail her around the world.

In 2006, shortly before Kicki and I headed into the frosty latitudes of the South Atlantic in which we still sail, WANDERER III crossed an ocean she’s been in and out of since she was new: the Eastern Pacific. We were eastbound for Chile, but we hardly felt any wind on the stern. Instead, we had a succession of calms and fronts, for a pattern of stop-and-go sailing. I found myself bent over our paper chart, still aboard from Chantal and Gisel’s time. The chart had character: Dried coffee stains created fictional islands. On a previous voyage I had taped blank paper to it, to enlarge the ocean it represented. A sextant sight represented by a small cross placed us at 39° 24′ S/95° 58′ W. I eventually became aware of many other penciled crosses spreading across the huge two-dimensional paper surface. My eyes ran up and down our longitude. We were 2′ away from 96° W.

That line—96°—stretched, unhindered by any landmass, northward toward Mexico, where it disappeared into continental obscurity. Southward it ran into the Pacific, and went unobstructed into one of the world’s loneliest patches of ocean, toward Antarctica. It’s a landless loner, 96° W, and once you cross it you are definitely on a long voyage.

WANDERER III lies becalmed in 2000 in the tropical Eastern Pacific, west of Chile. There is a noticeable swell, generated by the deep pressure systems in the higher southern latitudes.

I had just marked the chart’s sixth cross on that line—one of them Gisel’s, five ours—and I realized two more should be added, from Eric and Susan’s two circumnavigations in the 1950s and ’60s. That’s when it really struck home: this was WANDERER III’s eighth meeting with this remote longitude.

These fixes were nothing less than eight unique pelagic moments spaced over 50 years. What has allowed WANDERER to create them again and again and again? What, during 300,000 ocean miles, has allowed her to shake off two severe reef strandings, a full capsize, several knockdowns, and countless storms? Clearly, there is much that has worked.

And some that hasn’t.

Only 14 days into WANDERER III’s first voyage into the Pacific in 1953—from Panama westward to the Marquesas on the ’round-the-world tradewind route—the bananas in the forepeak were pretty well done. “Falling like autumn leaves,” Eric wrote almost poetically on February 8, 1953. He kept his log in a surprisingly non-technical style, written up in words rather than numbers, their position noted at noon each day. But on 4° 41′ S/96° 08′ W, his poetry ended. “The motion is awful. At breakfast the galley stove with its kettle and pot of boiling water was thrown off its gimbals. Ditched the last of the bananas.” And a little later: “…the motion is altogether too much.”

At 1,482 miles into the 4,000-mile passage, they had bypassed the Galápagos Islands. The wind had increased all through the previous night, and they tore along at 6 knots. “I tried to make her steer herself by easing the mainsheet and backing the staysail…. She is proving to be most unbalanced and with this beam wind will hold her course only for a few seconds. Giles should study the metacentric shelf!”

“Back to the drawing board, Giles!” he seems to be saying, nearly one year after WANDERER III’s launching. That’s almost heresy, and very unlike Eric. For a moment he doesn’t seem very pleased. “The sky is mostly overcast. This is not at all what I imagined the SE trades to be. A gloomy day. Before supper we rolled down the second reef. Susan is very tired and she had the first night watch, but failed to get much sleep, while I on deck could not keep awake.”

In hurricane-force winds, WANDERER III lies moored alongside the old whaling station of Grytviken during her first visit to the island of South Georgia in 1998–99. She is being held 10’ away from the jetty by long lines that at times stretched so much that the diminutive yacht touched the wooden jetty. Despite such weather, South Georgia has become WANDERER III’s favorite island.

WANDERER’s quick and jerky motion, and the strain of constant steering coupled with the lack of sleep, are the dominant features of the log. Remember: it’s all hand steering. There was no wind-vane steering yet. Sleep was a rare commodity in the short-handed ocean cruising of the 1950s.

WANDERER III’s long keel helps her to hold course while on the wind, and identical twin foresails set on poles keep her steady off the wind. I have never needed to hand-steer her for a lengthy period; I’ve always had her original self-steering wind vane in service. This unit is one of the two prototypes its inventor, Blondie Hasler, installed simultaneously on his famous Folkboat, JESTER, and on WANDERER III in the mid-1960s. It has logged 230,000 miles and still has many of its original parts; it has never given any problems, and it tricks me into thinking of WANDERER III as being almost perfectly balanced. During their first encounter with 96° W, Eric and Susan clearly thought otherwise. Not until far beyond the halfway point to Nuku Hiva could they finally celebrate that perfect day of glorious sailing, on a Friday the 13th, with rum punch and a tin of peanuts.

After their first circumnavigation, Eric reflected, “WANDERER III was probably as small a boat as any sober-minded individual with a proper respect for the sea would care to take across an ocean.” The 1950s mindset had guided her construction. The uncertainty at the time as to how small a boat could make it safely around, and how strong it would have to be, was addressed by slightly beefed-up dimensions in critical areas—the bilge, around the mast, and through a plethora of stiffening bulkheads locked in by stringers. Generally the Brits liked their yachts compartmented anyway, and not sweepingly open.

The fact is that WANDERER III had never once let the Hiscocks down. So they left England again, in 1959, for their second circumnavigation in this diminutive yacht, this time crossing 96° W slightly farther south of their first time with their course set on Mangareva, not the Marquesas. That longitude proved a handful once more:

On Susan’s suggestion we hove to for six hours, so that we could both get a bit of sleep. Let down staysail at 0600, terrific leeward lurches at times, she even threw a saucer from its rack. On this tack everything is the wrong side: Galley to windward instead of leeward makes cooking awkward, chart table to leeward sends the blood to my head—and as we both prefer sleeping on our right sides we are pinned hard on our faces and our poor old elbows, which have given us trouble before, get paralyzed. … Susan’s tummy is better, mine still troublesome.

This entry on March 6, 1960, really makes me wonder: why do I hardly register these rolls and lurches? Am I so oblivious, so insensitive to motion? Or is it because, never having had to hand-steer on an ocean passage except among ice floes, I’ve never experienced exhaustion like theirs?

At South Georgia, WANDERER III’s crew examines the remains of the stranded three-masted bark BAYARD, which once circled the globe in the name of commerce. WANDERER III still circles the globe in the name of curiosity.

Laurent Giles’s answer to the apparent shortcomings of WANDERER III was the 30' Wanderer class, a slightly wider version with more freeboard, a continuous coach roof, and a roomier interior. I’ve never sailed one, but, to me, aesthetically it is no match to the “Three.”

Eric’s laments may have denied WANDERER III from becoming the popular, frequently built design one might have expected it to be. Her voyages, after all, generated so many devotees. But after 110,000 miles, WANDERER III became the Hiscocks’ favorite yacht.

Gisel and Chantal sailed WANDERER III a third time around the world from 1974 to 1979. Unlike Eric and me, Gisel never wrote a word about her, and he hardly photographed.

But he is the real storyteller among us. His gift is to observe and take time for the small details, and to relate them across a table of steaming tea and dark German bread; he tells wonderfully winding stories that you can only listen to, not read. That’s how I got to know him in 1982 in Kiel.

Shortly before I first met him, he had crossed the Indian Ocean alone in WANDERER III while Chantal was delivering another yacht. During that trip, she was tragically lost at sea. Gisel told me after that he wouldn’t be sailing for a while. I left him my phone number, and he later called saying he wanted me to keep WANDERER III pelagic. That single conversation set the course of my life.

In 1994, the raw and fresh nature of New Zealand’s Fiordland was a welcome change after four years spent in the tropical South Sea.

Now in his early 70s, Gisel lives on Mallorca. Other than in an outrageous dream in which he told me, “Thies, I totally forgot to tell you: WANDERER has a basement,” I hadn’t seen him for eight years. Big parts of his WANDERER III story had eluded me. In fact, only one detail of their rendezvous with 96° W was revealed to me by a tiny clue: the sketched outline of a freighter near the equator on my inherited chart.

So, there he stood in Mallorca in the summer of 2015, tall and slim, a warm smile, with his upper body bent forward as ever. He’s carried this adaptation to WANDERER III’s dimensions into his later life. He and Chantal were both tall, and just didn’t fit into a boat specifically designed for the much shorter Hiscocks. They couldn’t properly stand upright in the cabin, nor properly stretch in their bunks. Where today our solid-fuel Sardine stove is placed beside the mast, their feet dangled in the air.

Luckily for WANDERER III, and for us, Gisel wasn’t the man for sweeping change and big repairs. Instead, he was into details. He could become completely absorbed with the shaping of small things such as our handmade lignum vitae winch handles, the boat’s carved cleats, and a Laurent Giles logo famously mounted to the bulwarks not by seven, but by 27 screws. All of these items are still there, and only his top-notch varnish work hasn’t endured. Sitting with him in a Mallorcan orange grove, I myself became keen on details. German dark bread gave way to olives, and tea to wine, while Kicki and I listened to his tales. During August 1975 at the Goudy and Stevens Shipyard in East Boothbay, Maine, he’d changed WANDERER III’s galvanized-steel push- and pull-pits to stainless-steel. And the spliced 1 × 19 wire forestay I had marveled at for many years? He’d only had it done because it could be done. And that freighter drawing on the chart? He had no idea. “But the trip,” he mused, “was all magic in motion.” Just like ours.

Our own first voyage into the Pacific was WANDERER III’s fourth, and her third between the Galápagos Islands and the Marquesas. WANDERER III self-steered, with hardly the need to adjust the sheets, for a 25-day nonstop repeat of the Hiscocks’ 1953 perfect Friday-the-13th weather. On my chart—Gisel’s old one—two straight lines of regularly spaced crosses ran almost parallel from the Galápagos Islands westward along the equator, marking Gisel and Chantal’s passage, and ours. Each of our new fixes clung on to Gisel’s as we moved westward. Adding Eric and Susan’s daily positions, it became a race of single performances, in the same boat, each sailed decades apart—by the Hiscocks in 1953, Gisel and Chantal in 1976, and by us in 1991. Sometimes we were a bit ahead, sometimes one of the other crews was—until 300 miles before our arrival in Nuku Hiva we hopelessly lost ground to a calm. Even when the wind returned, we would soon fall further behind by slowing down in a very different way.

WANDERER III has helped to shape the framework of a classic circumnavigation. You leave home, circle the world in constant progress along the tradewind route, touch places while on the move to somewhere else, and arrive back at the same spot within a set time. Typically this takes three years. Both the Hiscocks and Gisel and Chantal had made such voyages. And, until this point, so had we.

About with hepatitis B changed everything. I fell sick on an uninhabited Tuamotu atoll called Motutunga. We were alone, with no radio, nobody knowing our whereabouts. With me so weak, it was too tricky a place to leave, but also a beautiful one. It held me physically captive and captivated my mind’s eye, both at the same time. Looking back at Motutunga, I realize that it is very much there, ten years into living with WANDERER III, that her third story really began—the one with us and ours with her.

My hepatitis set something in motion that would let us break with the Hiscock continuum—from Panama to New Zealand in one season. In the early 1990s, foreign yachts needed a serious excuse to wait out cyclone season in French Polynesia. Arriving in Tahiti still weak, we qualified. But six months in Tahiti, and even some time on Moorea, didn’t lure me. As soon as I was halfway back in shape, we sailed north to Kiribati’s Line Group during cyclone season. Once there, we stayed, and our plans vanished. The restrictive cruising corset of the Hiscock Highway, the remains of a scheduled restiveness within us: it all dissolved. We had sailed into the slow beating heart of the Pacific. Without my illness we would possibly have continued to Samoa, then onward to New Zealand. Instead, we began to embrace the slowness of the Pacific, of its people, of an ocean filled by time. This set the tone for all our future voyages in the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and eventually in the Southern Ocean.

Similarly, my perception of WANDERER III gradually changed. Small yachting narcissisms were transcended. From merely being a yacht on a world trip she morphed into a fantastic platform in which to be in the world.

WANDERER III on a daysail along the South Georgia coast. She is in coastal-sailing mode: the dinghy is secured upright on the coach roof, and the firewood chopping block in the cockpit is not part of her seagoing equipment. The small sheet winches are original.

Before I left Europe in WANDERER III in 1987, I had toyed with the idea of eventually building myself a bigger wooden boat on my return—something along the lines of Laurent Giles’s DYARCHY, traditionally planked. The idea was to then sail it hard en route to Chile, recaulk the hull, sheathe it with copper where copper would be cheap—an idea exposing my deficiencies in macroeconomics.

In 2000, in Chile, nine years after that decelerating detour to the Lines, it had long been clear to us that the only copper-sheathed hull for us was WANDERER III’s. In her character, her simplicity, her smallness, her looks, in what she allowed us to do, in being perfect with all her small imperfections. Grow, yes, but not in size. If the challenge was to stay small, simple, and content, there couldn’t be a better boat.

At the start of the millennium, we had just tacked north through the Patagonian Channels following two years of burning peat and coal in the Falkland Islands and South Georgia. Despite a few broken frames and severe batterings in the Southern Ocean, she’d never leaked. We wanted to keep it that way and intended some preventive maintenance work in New Zealand.

With this in mind, we entered the Pacific for WANDERER III’s fifth encounter with 96° W, this time from Puerto Montt, Chile. The four previous occasions, all via Panama, had either been idyllic (Gisel’s and ours) or rough (the Hiscocks’). We were becalmed on this one. Under an endless gray sky, far off the South American coast, we had a modest breeze until we reached 17° 30′ S on the 22nd day at sea. Then, it suddenly felt as if we had slipped onto a magnet; everything abruptly stopped: the wind, our motion, even the sky’s grayness. We had entered into a seemingly permanent dreamscape.

“Sudden overwhelming clarity, with sharply outlined mountain ranges being nothing other than unexplored landscapes of clouds, islands floating in the far distance…,” I scribbled in the log on August 7, 2000. All we could do was patiently drift, not quite in control. If the sole purpose of 96° W had become to promote days completely unattached to human ambition and have WANDERER III make us watch them, it definitely succeeded.

The calm lasted only a few days, but it gave gooseneck barnacles a chance to take hold of WANDERER’s hull, extending our passage to Penrhyn, in the Cook Islands, to 54 days. From there we sailed to New Zealand, where we put her ashore for repairs. Calm days were in short supply after that: every single day, for one year, was devoted to her refit.

COURTESY OF JANICE ASLIN

Eric and Susan Hiscock specified WANDERER III’s construction and made their first circumnavigation in her between 1952 and 1955. Their example lit the way for a generation of world-roaming sailors in modest-sized yachts.

It was in New Zealand, in 1974, after the Hiscocks had sold up in the U.K. to become houseless sea nomads on their new ketch, WANDERER IV, that they received a letter from Bill Tilman, another sailing great of the time, whose various pilot cutters—most famously MISCHIEF—had taken him either to the far north or far south. “I am not surprised,” Tilman wrote, “that you are at a loss what to do next as you must have exhausted all the possibilities of that part of the world or indeed of all parts. Apart from where you are now the only peaceful places nowadays are those that are uninhabited.”

If this sentiment rang true 45 years ago, it does even more so today. Tilman’s wild places drew us. We had set our sights on spending long periods in the Thules of the world, where haulout facilities weren’t readily available. So I wanted WANDERER III not to be in any need of structural attention, or a slipway, for years. I was convinced, based on her high construction standards, that she could stand up to these regions well into old age. Her built-in longevity is the backbone of each of her eight crossings of 96° W. It is what gives her a dry bilge today.

There’s a triptych of factors that have contributed to WANDERER III’s longevity. First, the combination of owner, designer, and builder gave her a promising start. In 1952, Eric Hiscock knew what he wanted; designer Laurent Giles knew his trade; and the workmanship of the boatbuilders at King’s yard in England’s Burnham-on-Crouch was top-notch. All three understood the forces on a boat and the required structural elements. The builders chose their seasoned timbers wisely. The joints were perfect.

The second element of the triptych is the manner in which the builders put her together: the narrow-seamed, caulked hull was built with no glue at all, with an elm keel; spruce stringers; and white-oak stem, deadwood, and beams all of well-seasoned full-grown timber. The dimensions of all stressed parts of the hull, especially her iroko hardwood planking, were slightly oversized. And then there were her fastenings, almost all of which are now copper. Copper really is a wooden boat’s fountain of youth, and I’ve thus eliminated all iron from the structure. And where copper is too soft for service, as in ballast-keel bolts or floor timbers, there is aluminum nickel-bronze.

COURTESY OF JANICE ASLIN

Susan Hiscock.

But even the advantage of such a great start and exceptional construction wouldn’t necessarily have seen her sail 300,000 miles were it not for her three owners: Eric and Susan, Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and me. We all filled her with voyages, we all lived on her, we all adore her. She isn’t too big; she is small and pretty. She invites care. For her longevity, this counts as much as structural details. So does luck.

In 2003, on the first trip after WANDERER III’s restoration, we sailed her onto a reef in New Caledonia. The new frames I had just put in, combined with luck, her copper sheathing, and further repairs, helped us get over this and return to cruising. A shakedown cruise to Tasmania and New Zealand’s Subantarctic proved her tight and fit, so in late April 2005 we departed on a 71-day Southern Ocean passage from Dunedin, New Zealand, back to Chile, in the southern winter. On the 59th day, we reached a spot where God clearly played chess with highs and lows. Without any indication of change, it blew force 9–10 from the east. At 39° S, we were hove-to on the second of five stormy days. Imagine: five full days spent gliding backward over 96° W. Our minds were eased by two traits that modern yachts rarely deliver: the ability to heave-to and the comforting way she transmits sound.

WANDERER III heaves-to exceptionally well under trysail alone. The weight of her 10-ton hull and the long lateral plane allow her to hold her ground or, if necessary, even to climb upwind under sail against 40 knots or more—an essential quality for a small, low-powered boat such as she, especially along the coasts of the higher latitudes. It’s the one reason why we can consider taking her there at all.

Once hove-to, it felt as if we had opened a relief valve, released pressure, and stepped into a state of alert hibernation. As we closed the hatch and slipped down below, the high-pitched shrieking of the outside virtually fell away. It is below deck, especially in storms, that the tone a boat carries either encourages trust or causes it to crumble. On this sixth meeting with 96° W, WANDERER III’s comforting timbre kept any nervousness at bay. The boat looked after us for the duration of that five-day storm.

Something else did make us nervous, however. Our small Sony receiver picked up an outrageous warning. “Danger of falling spacecraft elements on June 16, 2005, between 0100 and 2300 UTC within the coordinates of….” Just where we were. “What more do they want to throw at us?” Kicki bleated. But eventually our chess-playing God made a move and allowed WANDERER III to complete her sixth crossing of the lonely longitude.

On New Year’s Day 2006, at 25° 30′ S, the seventh rendezvous was the inverse of the sixth: it was just as tedious, but this time absolutely without sound or wind, courtesy of an expanding Easter Island high. Our two-day-long calm when crossing this line in 2000, a little farther north, was like a hasty pit-stop by comparison. Whenever she’d come upon this longitude in the past 54 years, she’d left all signs of human industry behind. It was not so on this crossing. What I observed from WANDERER III’s decks this time was more worrying than any storm.

As I stared straight into the ocean, where the sun’s rays concentrically gathered in the blue, what I believed to be diatoms, dinoflagellates, or other plankton were in fact tiny particles of plastic. The deep blue upper layer was strewn with a loosely woven carpet of civilization’s rubbish. Wherever I looked were discarded shreds linked to the achievements of a much more buzzing world elsewhere. This wasn’t the North Pacific; this was a place remote from human concentrations. This was where Thor Heyerdahl, in KON TIKI, had crossed a pristine ocean in 1947. And it’s where WANDERER III pioneered small-boat circumnavigations only a few years later.

In 2004, WANDERER III makes a pleasure sail on a windy afternoon, one day before setting off from Tasmania to New Zealand’s South Island. The dinghy is inverted on the coachroof and the decks are tidy and clean for the ocean crossing.

In the early 1950s, the oceans were largely unspoiled. This is when WANDERER III’s story begins, along with human society’s environmentally troublesome acceleration. Since then our human activities have increasingly dissolved into the oceans, which store our excesses. As we sit in her cabin, surrounded by her almost unchanged interior devoid of modern conveniences, WANDERER III may be a time machine. Sitting on her decks, surrounded by the ocean, I think of her as a time witness. For us, she is the ideal vehicle to unpeel the layers of life. Staring into the ocean, I realized that I could only see this carpet in a calm. Once it blew again, the carpet rips apart and the ocean sparkles. Motion hides so much.

I wouldn’t have understood this had we rushed on and not drifted. WANDERER III will never have a large double bunk, a big engine, or much fuel capacity. Like Eric and Susan and Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and I have come to accept her spatial and temporal limitations. We just have to take our time. But with this comes a gift: We see different things and we see things differently along the blue side of our planet.

Thies Matzen has owned WANDERER III for more than three decades, and sailed her with his wife, Kicki Ericson, for more than 25 years. The couple were married at Grytviken, the abandoned whaling station on the doorstep of Antarctica, in 1999. They have spent a total of 29 months on South Georgia, and their book about those experiences, Antarktische Wildnis, was reviewed in WB No. 248. The book is available with an English translation at www.amazon.co.uk.