Thicker Than a Coat of Paint

Tom Townsend’s principles of design

Tom Townsend’s principles of design

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

The 43′ Penbo trawler-yacht ACADIA, launched as ADAGIO in 1969, was refurbished and reconfigured by Thomas Townsend Custom Woodworking and relaunched in 2008. She evokes Townsend’s signature aesthetic: spare and clean deck and interior arrangements, with an emphasis on functionality and keeping dry.

At Thomas Townsend Custom Woodworking in Mystic, Connecticut, the walls are painted a warm buff color and covered with poster-sized black-and-white photographs of family boats, old advertisements for classic trawlers and lobsterboats, paintings, and more photographs of past and ongoing projects. Townsend is an inveterate host, quick to laugh, and his shop is as comfortable and welcoming as his boats. There is a worn oriental carpet at the entrance, a waist-high stack of boat magazines next to the door, and a pair of unusually comfortable Adirondack chairs in front of the woodstove.

The shop has built and restored many boats, including two 1960s-era Penbo trawler-yachts built by Penobscot Boat Works (see WB No. 161)—and a handful of lobsterboats by several well-known Maine builders. Townsend recast the Penbos as simply as possible, replacing much of the original deck furniture and hatches with versions of his own and swapping out the hinged doors to the deckhouse for sliders to eliminate visual breaks in the house sides. As he often does, he also made good use of carefully rigged custom canvas awnings to lengthen the lines of the cabintops aft while keeping light the overall structure and visual effect.

The business, which has been active since 1995, skews slightly toward restoration and maintenance over new construction. Some of the new boats are built to designs by Townsend, but nearly all of the boats under his care—whether his own designs or those of others—bear a resemblance to one another. What unites this fleet? Part of it is the shop’s preference for workboat-inspired yachts, from sleek converted lobsterboats to full-bodied trawlers such as the Penbos. Part of it is the carefully considered and unusual paint schemes, which certainly stand out against white and dark blue at boat shows.

Townsend’s colors include earth tones and traditional greens, buffs, and grays, and occasional highlights of clay reds. Inspiration for these palettes often comes from the natural world: the greens, browns, and golds of a whole pineapple; a patch of eelgrass; and autumnal colors have all inspired his paint schemes. “So many of these colors are classic colors,” he insists, “it’s not like I invented them all....” And while it is true that many of the colors he uses are popular classics, his very particular combinations are a signature element of his style. Any boat that comes through his shop leaves not just with a paint job, but with a whole color program that is precise and carefully considered, all the way down to the canvas.

But there’s a lot more to Townsend’s approach to design and restoration than dressing up former workboats in surprising color combinations. It extends to a level of detail many builders would leave up to owners: an emphasis on simplicity and comfort, obsessively thought-out interiors, carefully designed dodgers and cushions, even hand-picked dishes and rugs. The result is a remarkable cohesion among a fleet of boats that wouldn’t ordinarily be seen as a family. And this gets one to wondering: What are the signature elements of the Townsend style?

LAURIE BELISLE

Thomas Townsend celebrates the relaunching of the Jonesport lobsterboat ALICE W (see photo below) in June 2014. He sold the boat to an owner in Maine, but has recently repurchased her.

Light and Color

Townsend’s sense for color and its impact on space and scale is deeply intuitive. In fact, painting theater backdrops and murals in high school was one of the only things that kept him in school. His mother is a talented, and still practicing, interior designer and illustrator trained in traditional drafting. Trompe l’oeil, the process of creating visual illusion with paint, figures into the boats occasionally, such as when diamond cutouts get a coat of black inside to make the outside edges appear perfectly crisp and bottomless. Such theatrical conventions are in evidence in Townsend’s lighting, too. Inset deck prisms can be found in the same cabin as old-fashioned gimbaled oil lamps and electric fixtures, but all the lightbulbs are placed on the forward sides of bulkheads so they throw their light ahead without being visible from the companionway. Sometimes stained-glass panels appear in bulkheads to bring a bit more color and light below.

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

Townsend restored the 35’ lobsterboat ALICE W, which was built by Vinal Beal in 1969. Townsend spent his youth admiring such boats, and was connected to this one by his former boatbuilding instructor, Jamie Houtz, of The Landing School in Arundel, Maine.

Most of the colors are custom-mixed, and the shop keeps recipes on file with several paint companies. Townsend and crew give the colors their own names in-house, most of which are amusing and unfit to print.

“Decks,” says Townsend, “are very important” when it comes to the overall visual effect, but they have to be practical. Using dark colors on low areas and light colors in high areas keeps boats “from looking like they’re going to roll over,” says Townsend, and reversing that pattern can make a boat look top-heavy. Interiors and overheads receive lighter colors to better reflect light and create a feeling of spaciousness. Color blocks are broken up in logical places to make maintenance as straightforward and unfussy as possible. “I try to make things easy to take care of, have easy breaks in the paint, and have a schedule of maintenance so you don’t have to do the whole bloody boat every year.” He also uses “good, tough paint.”

Varnish is typically absent from Townsend’s boats; rather, teak trim is left to turn silver with weathering, and countertops below are oiled. He does, however, occasionally use satin varnish belowdecks on small items such as poles, doors, drawers, and trim.

While he will spend hours trying to find just the right combination of colors, Townsend is quick to say, “It’s just paint.” As such it’s easy to change, cheaper than structural refits, and allows relatively low-risk unconventional choices.

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

Townsend’s 2017 display at The WoodenBoat Show included the PENBO trawler SCARLET (left), the 38’ Newbert & Wallace-built power cruiser CARIBOU, and an outboard launch of his own design. Lying outboard is the former sardine carrier GRAYLING, restored by Doug Hylan, which is now in Townsend’s care.

Unconventional Hardware and Machinery

Townsend is not interested in gadgets for their own sake, but he relishes a design puzzle. When a prospective owner requested a boat that would look and handle like a traditional lobsterboat but could ground out on the mud in front of his house at low tide, Townsend built a jet-ski engine into the boat (see WB No. 198). And although the shop crew is adept at traditional plank-on-frame construction, they are also very comfortable with strip planking and fiberglass-sheathed plywood if affordability is a concern.

THOMAS TOWNSEND

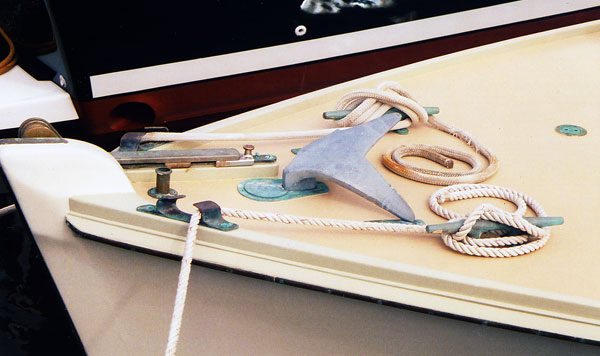

Townsend sources most of his hardware from consignment shops specializing in rare and discontinued items. The anchor-stowage system shown here, which is of his own design, neatly conceals the bulk of the stock below the deck.

Flexibility for singlehanding and ease of getting ashore are also important factors. Windshields swing open for good visibility and ventilation forward, and sliding side doors allow quick foredeck access from the pilothouse. The boats often have swim platforms and removable chocks and davits for dinghies. Townsend always prefers to carry a dinghy aboard rather than tow one on long passages, but he finds that chocks and davits can get in the way when the boat is at anchor. Wing nuts make them easy to remove for stowage.

Hardware is always bronze and usually sourced from marine consignment stores. When Townsend can’t find exactly what he’s looking for, he’ll work up patterns to be cast locally at the Mystic Foundry. He often will seek out replacement hardware that is heavier than the original pieces. For one restoration, he couldn’t find a set of bronze cleats he was happy with but found a huge galvanized-steel dock cleat with a shape he liked. He cleaned it up, filled its surface pits with Bondo, then took it to the foundry to use as a pattern for a bronze casting. The setup for an anchor roller is another construction detail Townsend has revisited many times over multiple restorations: “Aesthetically, it’s the death of a boat to hang all that nonsense off the bow, but if you’re singlehanding, the anchor needs a home and the home needs to be as nice as it can possibly be. And it needs to work.”

Original Designs

Townsend was raised in a family that spent time on the water in and around Oyster Bay, Long Island. As a kid, the boats he most admired were two old working Jonesport lobsterboats with diamond windows: “I would just sit in the cockpit with my chin on the rail and stare at those boats for hours.” He eventually watched one of them slowly sink at her mooring. Ever since, he’s been trying to get back to those Jonesport boats, with their curvy sheers, boxy cabins, squared-off windows, and clean trim.

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

Townsend began designing workboat-inspired outboard launches in 2005. NIFTY, shown here, is a raised-deck version of his Janet Dear 20.

Townsend’s original designs are mostly for small powerboats. While the lobsterboat style is his favorite—“it’s impossible to improve on a Jonesport boat,” he says—his own work evokes the pioneering powerboat designer William Hand, Penbo founder Carl Lane, and the sensible working skiff and yard boats of Long Island. He will frequently take a classic shape and modify it to suit a specific purpose—most often to make it more functional.

He had, for example, a Lawley tender that he loved, but it was too heavy and long to use as a dinghy on his own boat. So, he built a modified strip-planked version that was lighter, easier to handle, and shorter so that it would fit safely on davits on his own trawler without overhanging. He designed the center thwart to double as the daggerboard, which solved the problem of finding a place to stow it when it was not in use—and provided extra passenger-carrying capacity. This kind of two-for-one problem-solving and attention to detail are hallmarks of his approach.

EVELYN ANSEL

The helm area of the lobsterboat-yacht SALAR is a study in Townsend details. The paint colors are inspired by the natural world. There is virtually no modern plastic in sight, save for on the fire extinguisher. A handy pass-through in the bulkhead allows communication with the galley—and easy transfer of food and drinks.

Interiors

EVELYN ANSEL

SALAR’s spacious galley is connected to both the helm area and the saloon. Note the diamond-shaped cutouts—a distinctive Townsend touch—in the locker doors.

Townsend believes that one should “make the boat more like a house, and the house more like a boat.” This idea also explains a few things around the shop, such as the brass rubbing strip fastened to a section of floor next to the tablesaw: “We’re always hauling sheets of plywood through here; it’s to keep the threshold from getting too beaten up.”

Interiors, he says, should be comfortable, beautiful, and easy to live with and get around in. There should be plenty of light and ventilation, and the space must be warm and dry. The boats are carefully appointed, and every element aboard has a purpose whether fastened down or not. For example, “every boat needs a stool with a handle in the middle. You can use it for about twelve different things. Getting on and off the boat, reaching things, to put your feet up.”

His large boats all have woodstoves. They are also filled with little human touches such as bud vases in the corners of the pilothouses, “which look great! Makes it feel like a limousine”, he says, “until in the winter you forget to empty the water and they all freeze and crack.” Other important details include oversized cushions and generous bunks intended to maximize comfort rather than berth space. “I don’t need to be able to sleep 10 people,” he says, “but on a 36′ boat you should have 22 great places to read.” For years, Townsend has been adorning his boats with oriental-style rugs. They look nice, but they are also there for practical purposes: they provide some measure of protection to the cockpit and cabin soles and, more important, protect bare feet on the way to making a cup of coffee on a cool morning.

EVELYN ANSEL

Lanterns, removable chairs, area rugs, judicious use of unfinished teak, and color choices all combine to create the Townsend "look"; these items are as critical as the built-in items.

Townsend likes to take out or open up bulkheads whenever possible for improved socializing and to make interiors feel more spacious. He might, for example, open up the aft end of a galley to the pilothouse, providing a pass-through for sandwiches and a sightline for the helmsman; he might similarly open up the forward end of the galley to the saloon to encourage companionship. “You don’t want to cook in a closet,” he says. On one of his Penbos, he even fitted a little folding telephone-booth seat in the galley. Countertops have no fiddles, because Townsend likes to sit on them. All the teak and mahogany gets an oil finish—or nothing. He has been known to paint previously varnished paneled bulkheads, too, sometimes to the dismay of former owners. “But,” he says, “you just can’t hang art on a varnished butternut bulkhead.”

Townsend often finds that the most elegant way to accomplish something is also the simplest and most comfortable way. Hooks latch into tiny carved sockets on the tops of doors and folding panels; turn-buttons keep plexiglass windows in place. Still, Townsend admits that his greatest weakness is probably his tendency to agonize over small decisions. For him, the structural problem-solving of restoration feels straightforward, but he will go back and forth over an arrangement detail or wrestle endlessly with a color choice. His crew (see sidebar)—Mike Coyle, Mike Lamb, and Rynn McTeague—are indispensable and patient sounding boards when it comes to his decision-making.

The Boats Speak for Themselves

THOMAS TOWNSEND

Townsend prefers to carry, rather than tow, a dinghy. Removable chocks allow the onboard hardware to virtually disappear when the dinghy is in the water.

When his father gave Townsend the option of paying for his college education or buying him a boat, Townsend took the boat. He bought and restored a 31′ Jorgensen Sea Skiff and then sold it to pay for boatbuilding-school tuition four years later. This would turn out to be the first of many projects to follow this pattern. Indeed, most of Townsend’s large restorations have been boats he acquired for himself. He almost always has a serious personal project going on alongside his work for regular customers. After restoring and then using a boat for a few years, he eventually sells it to make room for the next one. This has had a profound effect on the evolution of the business; these non-commissioned restorations let him build out a hull completely on his own terms. The prospect of several years of use gives plenty of incentive to work overtime and weekends, and the result informs design choices for the next restoration. By then offering these boats for sale, Townsend has created demand for exactly the kind of boat he wants to restore and build for himself. It also sets the bar for what customers can expect if they allow him to exercise full artistic license with their projects, whether they are new-builds, refits, or restorations.

Townsend has purposefully kept his business small and community-oriented. He never has more than four people working with him in the shop, he doesn’t own a laptop computer, and he still hand-writes invoices. He doesn’t sell plans for his own designs, and his website is currently just a landing page that he has yet to fully construct.

None of this is out of stubbornness or a lack of desire to learn or grow the brand. In fact, he’s been meaning to expand the website for some time, and would like it to include more photographs and videos. But he’d simply rather be building boats than marketing. His distinctive approach has created enough demand that he has never had to advertise. His shop’s relatively low administrative demands and seasoned crew allow him to be personally involved with every project.

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

Partial bulkheads and generous use of light—but not white—paint create a warm, cozy, but spacious-feeling interior.

He’s not sure what his next project will be, but the result will no doubt look perfect in its surroundings—as if it’s always been there—when it lands at the fuel dock at the local lobster pound.

Evelyn Ansel splits her time between the Hart Nautical Collections at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the Herreshoff Marine Museum of Bristol, Rhode Island. She currently lives in Providence, Rhode Island, with her boatbuilding partner and their sardine-loving cat.

The Townsend Crew

THOMAS TOWNSEND

The Townsend crew, from left: Mike Coyle, Rynn McTeague, and Mike Lamb.

Townsend has great admiration for his three-person crew, Mike Coyle, Mike Lamb, and Rynn McTeague. Coyle has been with Townsend for more than a decade and is responsible for a lot of the heavy lifting—systems, engine and metalwork, big timbers and planking, and generally “anything below the rail.” Lamb, formerly a mate on the schooner BRILLIANT, is great with fine details and finishwork, leather, and rigging. Both Mikes have an impressive amount of sea time, and between the two of them “they can put any boat anywhere it needs to be,” says Townsend. McTeague joined the shop in 2018 and does a little of everything. All three have input when it comes to construction elements, design, and finish work. Townsend says that these three are the backbone of the business. —EA