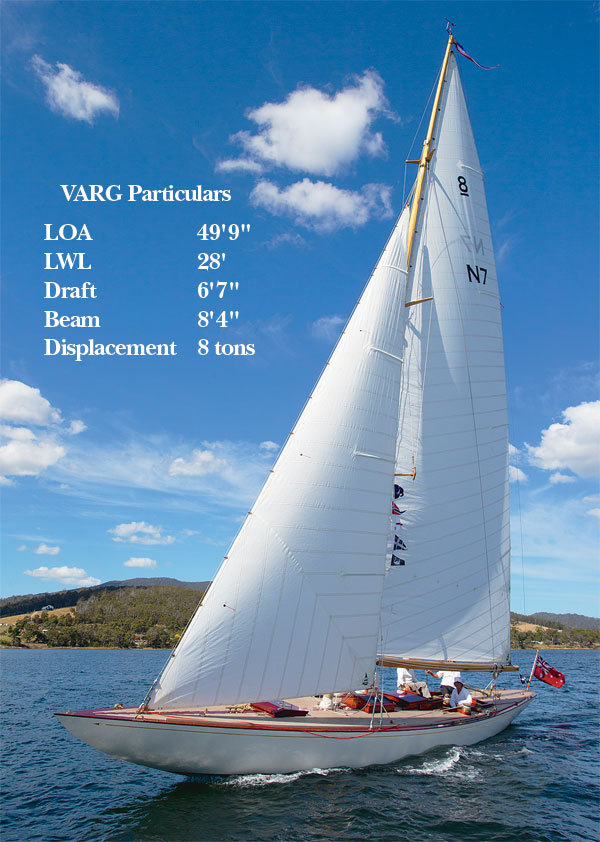

VARG

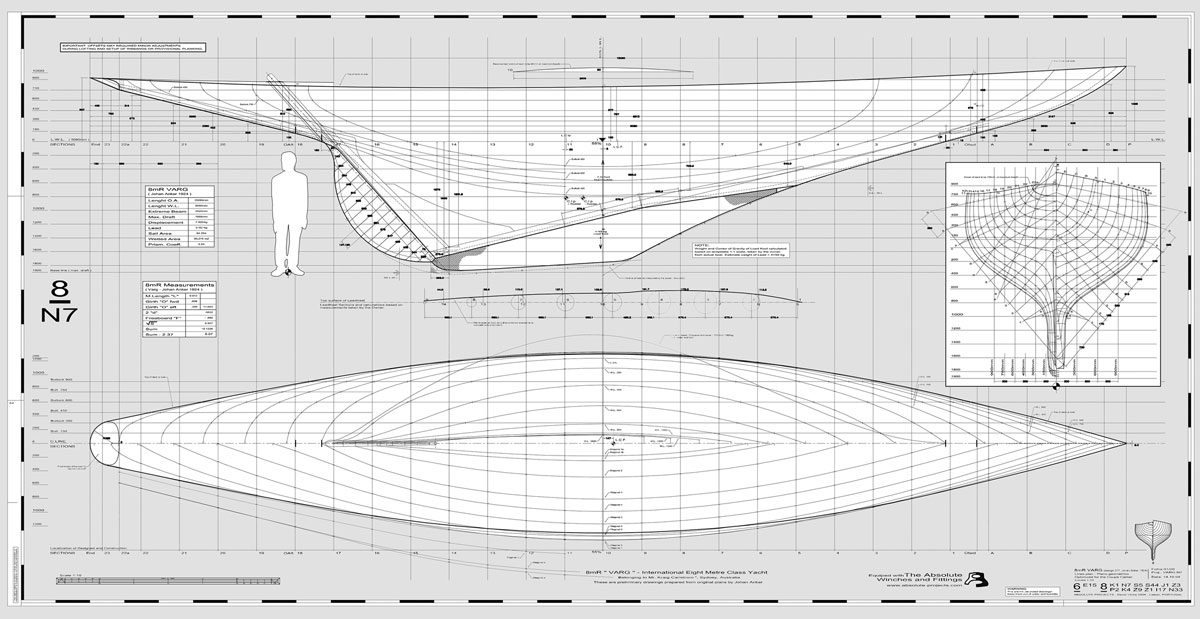

Re-creating a 1924 Johan Anker 8-Meter

Re-creating a 1924 Johan Anker 8-Meter

Kraig Carlström

Johan Anker designed the 8-Meter-class sloop VARG in 1924 for a British yachtsman. In 1927, she was sold to an Australian owner, who had her shipped to Sydney.

In 1924, the Norwegian wine merchant and yachtsman Alfred W.G. Larsen commissioned Johan Anker to design and build an 8-Meter-class yacht that he hoped would be fast enough to beat the best of the British boats racing on the Solent. Anker responded by drawing a beautifully proportioned long and slender sloop to be named VARG, the Norwegian word for wolf. Built in just six months at the Anker & Jensen yard, she was planked with mahogany over rock elm frames and strengthened amidships with galvanized steel frames. Her keel, stem, and sternpost were of oak and her deck and spars of Norway spruce.

Kraig Carlström

Photographer Kraig Carlström was smitten with the boat despite her condition, and committed to a multi-year restoration. Rebuilt from the keel up, she’s seen here soon after her relaunching.

VARG was successful in English waters, and this success continued under the ownership of Lord Henry Forster, a former Governor General of Australia who raced her for two seasons with the Royal Yacht Squadron and in 1927 sold her to the Australian music publisher Frank Albert. Albert had VARG shipped out to Sydney as a gift for his 23-year-old son, Alexis. Frank Albert’s wife, Minna, who was Swedish, didn’t much care for the somewhat daunting name VARG, so she chose to call the boat NORN—a softer reference to the all-powerful maidens of Norse mythology who are said to rule the destinies of gods and men. NORN was to become one of Australia’s most celebrated racing yachts. Meticulously maintained by her professional sailing master, Andrew Lundquist, she reigned supreme at Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron for over 30 years.

When the Albert family sold her in 1958, NORN (ex-VARG) was still in A-1 condition, but in the hands of a succession of owners who lacked the money and the sensitivity to maintain her, she slid into an inexorable decline. In time, her classic lines were vandalized by a series of ugly accretions, including a hideous cabin aft and the brutal truncation of her long and graceful counter stern. Her hull was sheathed in a crude skin of plywood and fiberglass and her rusted steel frames removed; she became a parody of a boat, a decrepit rotting hulk too weak to leave her mooring. As if to hide her shame, she sank to the bottom of Sydney Harbour, where she remained for weeks until salvaged and put up for sale. She was inspected by plenty of dreamers, but none of them had an imagination vivid enough to perceive anything other than an old boat in the terminal stages of decay.

Kraig Carlström

Impeccably kept for many years, VARG eventually fell into a long period of neglect and decline.

It would take a man of profound aesthetic sensibility to appreciate that beyond all the debris lay a rare and beautiful example of one of the world’s most famous and gifted yacht designers. That person was Kraig Carlström, a lifelong racing sailor who also is one of Australia’s leading photographers. Although he saw VARG as a once-in-a-lifetime restoration opportunity, he was in for a dreadful shock as soon as he stepped aboard. Over 6′ of putrid water sloshed about in the bilge, and her stripped-out interior was streaked with rust and redolent of the sour smell of rotting timber. Although most of us would have quickly leapt ashore and fled, Carlström found himself locked in the giddy grip of a romantic obsession in which his heart overruled his head. He had fallen in love with an 80-year-old boat.

Carström stumped up the AU$25,000 asked by VARG’s then-owner, but wisely made the deal subject to inspection by a qualified marine surveyor. He assigned the task to Doug Brooker, one of Australia’s best-known and most respected wooden boat builders. In the several hours they spent examining all of the boat’s defects, the no-nonsense Brooker produced a pocketknife and thrust it here and there into her timbers, deftly demonstrating that she was little more than a waterlogged sponge held together by the tens of thousands of staples in her plywood sheathing. Brooker gave Carlström a terse three-word report: “She is finished.”

Kraig Carlström

The Portuguese naval architect David Vieira of Lisbon drew many details for VARG’s restoration, as well as re-creating her lines drawing and sail plan.

Carlström’s money was returned and that should have been the end of the matter. But for months afterward he was haunted by the specter of the old boat that seemed to be crying out for help. After a holiday in Sardinia where he and his wife, Carolyn, were inspired by the classic yacht regattas they watched on the Costa Smeralda, Carlström came home to Sydney, ignored Brooker’s warning, and offered the owner AU$17,000—roughly half the original asking price. With no one else even remotely interested, the deal was seized upon with alacrity. Thus Kraig Carlström found himself the owner of one very shaky old boat.

Brooker had advised him that if he insisted on going ahead with a restoration, he should speak with the craftsmen at the Wilson Brothers yard at Port Cygnet in southeastern Tasmania where since 1863 four generations of the same family have been building beautiful wooden vessels. Carlström had the boat trucked by land and sea the more than 1,000 miles south to Tasmania, the lovely island state that is in many ways similar to Maine—a place of great natural beauty, steeped in maritime tradition and a stronghold of Australia’s small but dedicated community of wooden boat owners. At Cygnet, a sleepy little backwater at the head of the picturesque D’Entrecasteaux Channel, the wreck eventually rolled to a halt outside the Wilsons’ waterfront shed. Michael Wilson remembers the moment well. “As soon as I laid eyes on her,” he said, “I shook my head and told Kraig straight out: ‘This is a boatbuilder’s worst nightmare. There’s no way we can restore her. Don’t even think about it.’

“She was sad,” he said. “She was rotten. There wasn’t a skerrick of structural integrity in the hull. In the 1960s she had been sheathed with two or three layers of plywood fastened with thousands upon thousands of stainless-steel staples and covered by a thin fiberglass cloth. But that had simply accelerated the rotting of the mahogany planking underneath. Over the years the water had seeped in and turned her into a big, soft sponge. She was such a mess. There were supposed to be steel frames in the hull, but they had just rusted right away. The stern had had 3′ cut off, probably in a crude attempt to get at the rot.”

Wilson’s professional advice was to salvage the lead keel and start from scratch, building a new boat on identical lines. Carlström agreed. Thus his obsession with restoration gave way to an equally obsessive passion: the re-creation of VARG exactly as she was in 1924. The result is a breathtaking masterpiece in fine woodworking. Wilson and Warren Innes, the master craftsmen who worked on VARG for more than six and a half years, have not only built a boat, but have created a work of art.

Kraig Carlström

The plank seams were caulked with cotton, but instead of being payed with putty in the usual manner they were dressed off with a wedge-shaped Huon pine spline, which was driven in and glued to both of its mating planks.

The timber selection took years and involved the use of only the very best of Tasmania’s unique and beautiful endemic species. Much of the exquisitely figured honey-blond Huon pine used in the hull was milled from trees that were over 2,000 years old when they were felled in Tasmania’s remote mountain gorges back in the 19th century. The aromatic, resin-rich Huon pine (Lagarostrobus franklinii) is now a rare and protected species that cannot be logged. The timber that is currently available has been salvaged from dam construction sites and wild river systems where logs have lain submerged for well over a century. Obtaining the highest-quality Huon proved to be one of the boatbuilders’ biggest and most frustrating challenges.

With another boat in their Cygnet shed (the 65′ L. Francis Herreshoff ketch GLORIA OF HOBART), it would be four years before Wilson and Innes could start on VARG’s construction. Carlström used that time to search for timber. He was lucky to locate a stash of Burma teak and magnificent Brazilian mahogany in Queensland. The rich red mahogany was more than enough for the covering boards, the nibbed kingplank, hatches, skylight, and cockpit fitout. The teak went into the deck and the cockpit sole. Clear-grained celerytop pine for the keel, stem, sternpost, and deckbeams was easily sourced in Tasmania together with the exceptionally hard blue gum for the frames. But sourcing good-quality Huon pine threw up what turned out to be an almost insurmountable challenge that cost the project significant time and money.

At a mill at Lynchford in northwestern Tasmania, Carlström had purchased a large trailerload of what was purported to be good boatbuilding-grade Huon, only to find it far from the perfection that Wilson and Innes were looking for. “There were lots of knots in the timber,” Wilson said. “It was bony and not to the thickness we required. We wanted inch-and-an-eighth, but a lot of it was only inch. We couldn’t get the right-sized planks out of it. We would have been happy with 25′ planks, but 16′ seems to be the maximum these days. Kraig and I had to drive all the way back to Lynchford with the trailerload of rejected timber. The saw-miller admitted it wasn’t the best quality. We spent three or four hours pulling timber out of his sheds.

“We really should have spent three days there picking through all he had. We ended up having only just enough good timber. Twenty or thirty years ago we kept a big stack of beautiful Huon pine boards in our shed and every one of those could be cut into really lovely planks. Poor Warren had the difficult job of trying to make decent planks out of the stuff we had.”

Kraig Carlström

VARG’s original construction incorporated much steel—a good choice for the sake of strength but not for longevity. The re-created boat has artful and strong bronze floor timbers.

Innes remembers it well. “We just could not get the right timber,” he said. “We found something wrong with every piece of timber we wanted. That was the most frustrating thing of the lot. We spent more time trying to pick out a particular piece to do a particular job than we did in actually doing the job.” That frustration, he said, persisted through the entire project. “Tasmania is renowned as the home of magnificent timber, but I’m afraid it has now become very, very hard to get good-quality boatbuilding timbers. When you build a conventional planked boat the grain has to be perfect because you’re bending and twisting timbers, and if the grain is put under too much strain it can break. If the boat falls off a big sea, that plank can let go. That’s a big concern. I’d come home at night and worry whether or not I’d done the right thing. You shouldn’t have to do that.”

Kraig Carlström

The hull was made bottle-smooth and the bottom fiberglassed up to the waterline. Here, the deck framework awaits planking.

Kraig Carlström

The builders coated all of VARG’s timbers with 13 brushed-on coats of thin epoxy. The resulting surface was hand-sanded so as not to remove this coating from the corners. The interior hull surface received six coats of varnish.

But timber was not the only issue in re-creating VARG. The lead keel, the only significant piece of the old boat that could be saved and reused, also had major problems that took the builders several weeks to put right. Both Wilson and Innes came to wish that the keel had been discarded along with the tired old hull. Wilson believes that when the keel was originally cast in Norway, the mold must have collapsed during the pour. “The port side had a 7 or 8mm bulge in it,” he said, “while the starboard side had a corresponding hollow. I had to plane all the bulging lead off and epoxy-glue it back on the other side to bring the keel back to its true shape.”

The hollow and bulge turned out to be the least of the problems with the old keel. When Wilson and Innes poured new molten lead into the old boltholes, they discovered huge voids within the keel. “We were pouring lead for what seemed like ages,” Innes said, “but it was just disappearing. We saw steam coming out of a hole at the other end so we figured out there must have been a huge cavity hidden in the middle of it.” Innes believes the fault may have been with what he calls “the gunk” and inferior lead that went into the original pour back in 1924. “They may have used old lead pipes,” he said, “and perhaps some ingots went into the mold so that the molten lead never really flowed around them. It took about 150 kg (330 lbs) of lead to fill those voids. The keel had weighed 4,300 kg (9,480 lb) when it was taken off the old boat. It’s up around the 4,500-kg (9,920 lb) mark now.”

Kraig Carlström

VARG’s deck is made up of a layer of Huon pine, followed by marine plywood sheathed in Dynel, and finally the layer of Burma teak seen here. The covering boards and kingplank are of Honduras mahogany. The initial Huon pine layer is V-matched, giving the overhead the planked effect visible in the interior photo below.

Kraig Carlström

With only finishing touches to go, such as the gold-leaf covestripe, the epic six-and-half-year restoration of VARG nears completion.

Wilson and Innes mention these things in response to the carping few who express incredulity that it took two highly skilled tradesmen six-and-a-half years to build an 8-Meter yacht identical to one that was originally built in just six months back in 1924. “Quality work takes time,” Wilson says without apology. “We don’t waste time. We invest in time. We take the time required to do the best possible job. Perfection has no finish line. Johan Anker drew a set of really beautiful lines when he created VARG on paper. I think we’ve done the boat proud. We’ve given her the finish she deserves.” No one is disputing that. Wilson and Innes have done an absolutely superb job, and Carlström has no doubt that VARG is up there with the best of the world’s custom-built boats. “She is a work of art,” he says, “an absolute joy in every respect.”

Many creative talents were needed to make VARG’s re-creation a success. Chief among them has been the distinguished Portuguese naval architect David Vieira, who obtained Johan Anker’s original lines from the archives of the Norsk Sjøfartsmuseum, Norway’s national maritime museum in Oslo, and used them to produce scores of detailed drawings covering every aspect of construction. Vieira is one of the main figures in the International 8-Meter Association and has built up an impressive business in Lisbon catering to the restoration needs of many of the world’s finest classic yachts. One of Vieira’s specialties involves the custom designing and casting of bronze hardware, and he made many of VARG’s fittings.

Kraig Carlström

Launch day! VARG slides from the Wilson Brothers shed in Tasmania in November last year.

Kraig Carlström

VARG’s interior was given as much attention to detail as was her deck. Tufted leather covers her elegant settee cushions, while the plumbing in the head and elsewhere is meticulously done.

Kraig Carlström

VARG makes a late-season outing on Tasmania’s D’Entrecasteaux Channel earlier this year.

John Lammerts van Buren, a Dutch woodworker and sailor who runs his own Sitka-spruce mill in Alaska, supplied the 200-year-old clear-grained spruce used in the mast and spars which were beautifully made by Cygnet boatbuilder Andrew Denman. Colin Anderson of Melbourne built the sails, spending uncounted hours hand-stitching brass cringles on the narrow-paneled main, jib, and genoa. Meticulous hand-stitching of this caliber has not been seen in an Australian loft for more than half a century, the only exception being Anderson’s own classic gaff-rigged 8-Meter ACROSPIRE.

Sean Langman took on the task of making and installing all of VARG’s standing and running rigging. Langman, who is one of Australia’s most experienced yachtsmen, had the pleasure of taking VARG’s helm for her maiden sail from Cygnet to Dover in a 30-knot southerly. With no reef in the main, VARG sliced through the lumpy seas and remained steady and beautifully balanced. Both Langman and Carlström came ashore wearing grins that continue to animate their weather-beaten faces. One can understand why.

In the 50 years in which I’ve been writing about boats, I have had the privilege of seeing a great many very fine vessels all over the world. In all that time I have never seen a racing yacht more beautifully designed and built than the 8-Meter VARG. In every respect she is a breathtaking example of the boatbuilder’s art—a genuine classic.

Bruce Stannard is a regular contributor to WoodenBoat.