Cole Estep and the Mallows Bay Fleet

The Construction of the Ship-Shaped Islands on the Potomac

The Construction of the Ship-Shaped Islands on the Potomac

In a famous book titled How Wooden Ships are Built – A Practical Treatise on Modern American Wooden Ship Construction (PDF), published in 1918, author Cole Estep takes on the challenge of enticing and educating a new workforce of boat builders, aiming for nothing less than a “revival of the art of wooden shipbuilding.” His book is manual for constructing the largest fleet of wooden ships ever built. At the end of this piece, we will show you a marvelous and unexpected maritime heritage preserve in Maryland where these same ships can be seen and explored by boat today.

“Ships, ships—and more ships!”

By 1917, the scourge of the German U-boat had decimated about one fifth of the world’s merchant fleet, according to “The Last Boom,” Bill Durham's article in WoodenBoat #40 (presented below). President Wilson wanted new cargo ships to be built as quickly as possible, invoking the Urgent Deficiencies Act of 1917. The Emergency Fleet Corporation, which was the shipbuilding arm of the War Shipping Board, placed contracts for 1,218,000 tons of wooden ships, and about half that amount of tonnage, 642,000 tons, of new steel ships. The popular belief was that new wooden ships could be delivered faster than steel ships, and that the raw materials, the large stands of Douglas-fir and yellow pine, were close at hand in the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest and of Georgia. Estep writes in his preface, the universal cry was “ships, ships—and yet more ships!”

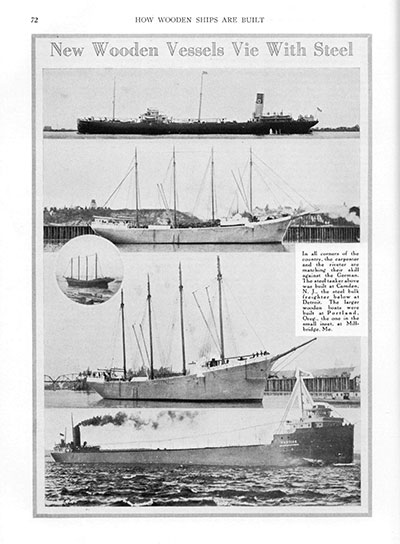

“New Wooden Vessels Vie with Steel”

How Wooden Ships are Built — A Practical Treatise on Modern American Wooden Ship Construction (PDF), with 200 Photographs and Drawings, by H.Cole Estep. The Penton Publishing Company, 1918.

In dramatic photographs and drawings, Cole Estep's book gives basic instructions on how to build a fleet of large wooden auxiliary ships, using “the boundless supply of timbers of the largest sizes” from Washington and Oregon, along with southern yellow pine from Georgia. He makes a point of using “a permanent source of supply of the highest class of lumber for shipbuilding.”

Lumberjacks, farm hands, and clerks were brought in to the shipyards to work for fifty cents an hour, because a lot of unskilled labor was required to start construction of these ships as quickly as possible. Estep’s intention was to write an introduction to ship construction for these novice shipbuilders. These men would have to learn to bend planks as large as 6″ by 10,″ drive drifts 6′ long and an inch in diameter, and move timbers up to 100′ long.

Hand tools were used—adzes and axes, hand planes, bits and chisels—along with a few large air-driven tools such as band saws, circular saws, and boring augers. Over one million tons of wooden shipbuilding were contracted in a few months time, and 202 ships were completed. These ships used huge amounts of old growth wood from the Northwest and elsewhere. For a single 281′ wooden steamer, the Framing Schedule called for 440,000 board feet of Douglas fir, and of those, 80 timbers had to be 30′ long, 12″ by 26″ trimmed for framing.

Among other things, Estep wanted to answer the question “How large may wooden vessels be built?” His book makes the case that wooden vessels of 3000 to 4000 tons deadweight capacity were possible. These ships were up to about 300 feet long, 40 to 50 feet in beam, with steam power plants of 1,400 horsepower. Estep describes the newest designs for modern wooden ship construction, slab-sided like a Great Lakes freighter, with steel strapping reinforcements inside the planking, and sometimes double-diagonal planking, and thick internal ceiling planks. He includes several beautifully detailed construction drawings showing the differences between these and older cargo sailing hull designs built in earlier centuries.

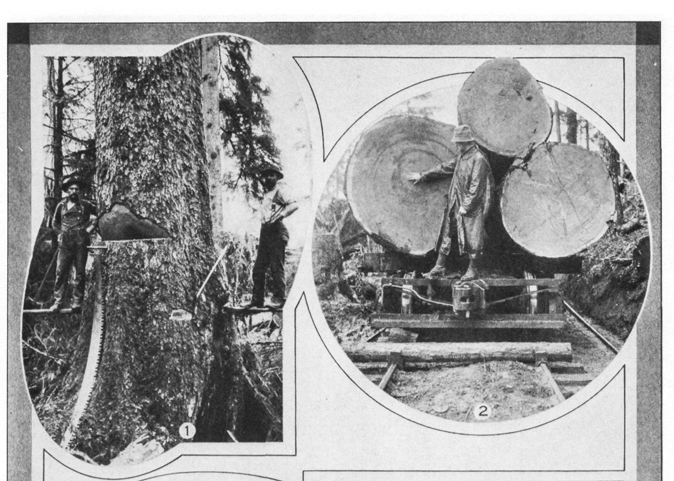

Old growth timber from the Northwest forests, Cole Estep, page 11.

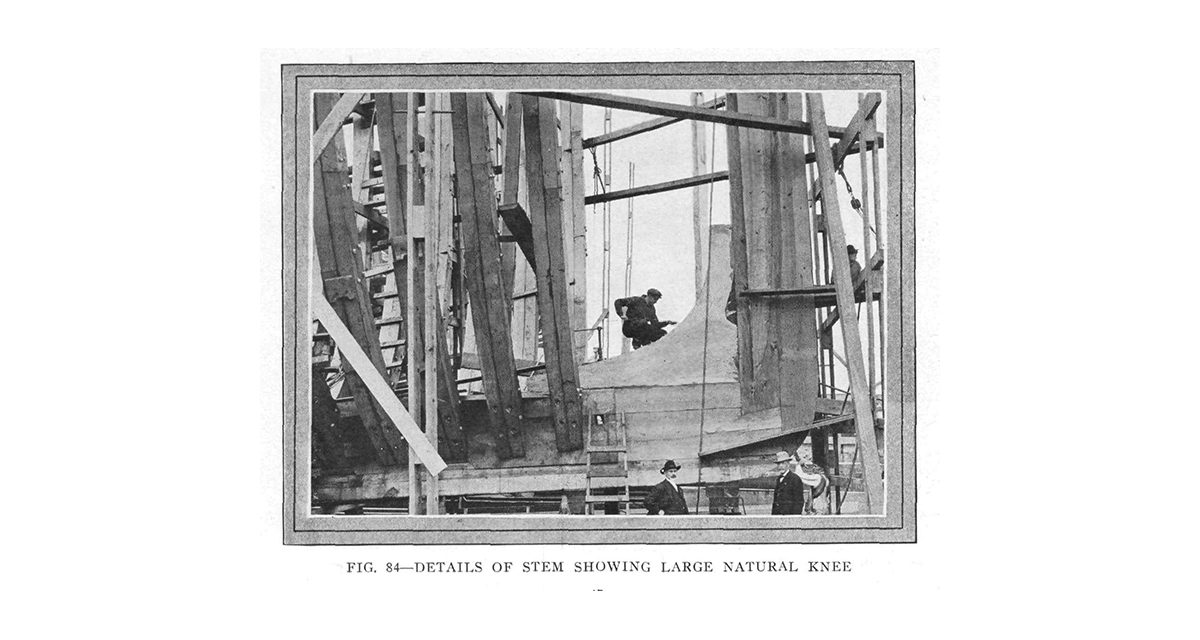

These timbers, and the monster saw shown on the far left, show the scale of the work involved. Estep’s photographs usually show a human figure somewhere among the huge frames, or perhaps a wooden ladder nailed on a vertical timber, showing the human scale of the frames, and of the ships themselves.

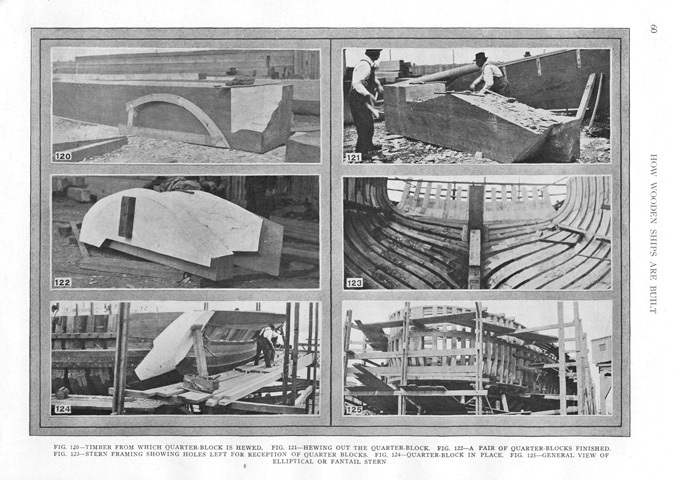

Here on page 60 in Estep’s book, a huge section of timber is ready for shaping. The upper right Figure 121 shows the two men starting to the hew the rough piece. The middle figure shows two finished blocks shaped to the new quarter pieces, and on the right, the gaps in the transom where the pieces will be fitted. In Figure 124, the pieces are set in place in the transom stern.

Durham Explains the “Emergency Fleet”

Bill Durham gives the long view of the construction of the “Wilson Wood-row Fleet” and subsequent collapse of this huge wooden ship building experiment in WoodenBoat No. 40, page 94. He briefly explains the coming-of-age of the American maritime heritage to 1915, and the boatbuilding boom of the great wooden Emergency Fleet—a fleet of large ships that was larger and more effective than the whole fleet of 19th century clippers, he says.

The article makes good use of the Estep book, and of another reference book for boatbuilders of that time written by Charles Desmond, Wooden Ship-Building. The pages of Desmond’s book present tables from Lloyd’s rules for building ships and other data about wood, fasteners, and fittings that the shipwright would need to know. He includes ship plans and photographs of ships under construction, and many detailed sketches of interior joinery, scarf joints, molding, hinges and frames. We will cover Desmond’s interesting reference book in a later entry on this site.

But what had been a shortage of ships before the Great War turned into a shipping surplus by late 1919. This fleet of “wooden ships of 1918 were sturdy, well designed, and for the most part, well built,” writes Bill Durham, but within a year or so wooden ships were no longer needed; steel was the thing and wooden freighters were set aside, before many of them were even completed. Some were never “engined”, were made into barges, others became firewood, or made their way to Mallows Bay, Maryland, for “final reduction.” All that hard labor, all that old growth timber. By December, 1920, 285 wooden ships, each costing almost $1,000,000 to build in 1918, were discarded.

What is the story of these ship-shaped islands?

These green and growing islands are clearly visible on Google Maps. They have been moldering away on the Potomac River, 30 miles south of Washington, D.C., and evolving from wooden ship to green island since the 1920s.

These vessels are the remains of the Emergency Fleet of wooden steamships and schooners described above and in Cole Estep’s book. Of those nearly 300 wooden Emergency Fleet steamships that were discarded, at least 152 ended up in Mallows Bay within nine years. Today the remains of about 30 percent of the entire wooden steamship fleet lie in this embayment. They are dramatic wooden artifacts of a herculean construction project nearly 100 years old. Bill Durham noted in his article that the men who built these ships during the Great War, who may have been farmers or clerks in 1916, sometimes counted those years in the shipyard as a peak experience of a lifetime. They remembered the name of each ship they worked on, long after the ships themselves were discarded.

The remains of these large wooden hulls have taken on a load of sediment over the years, evolving into ship-shaped islands, with rich ecosystems blossoming in biodiversity. The timbers rising up out of the Potomoc may be some of the same timbers rising in build in the photographs in Estep’s book. The Maryland Department of Natural Resources carries an informative article called the Ghost Fleets of Mallows Bay by Donald G. Shomette.

Kayaking in Mallows Bay

Mallows Bay has been nominated as a National Marine Sanctuary, and has become popular place to kayak as long as you watch out for the spikes of the old ships rising up to the surface. A launching ramp was built in the area in 2010.

National Trust for Historic Preservation: https://savingplaces.org/places/ghost-fleet

Maryland Department of Natural Resources: https://news.maryland.gov/dnr/2016/12/21/ghost-fleet-of-mallows-bay/

Q.Foster, Research Associate, WoodenBoat