Lessons of the BOUNTY

Drawing experience from tragedy

Drawing experience from tragedy

WB No. 233: Lessons of the BOUNTY — We’ve received numerous requests for reprints of Capt. Andy Chase’s article “Lessons of the BOUNTY: Drawing experience from tragedy.” That article recounts the sinking of the replica vessel BOUNTY during Superstorm Sandy on October 29, 2012. Many readers have found Capt. Chase’s summary of the lessons of that catastrophe to be invaluable to their own vessel management, and so Chase and illustrator Jan Adkins have offered its republication here, in its entirety.

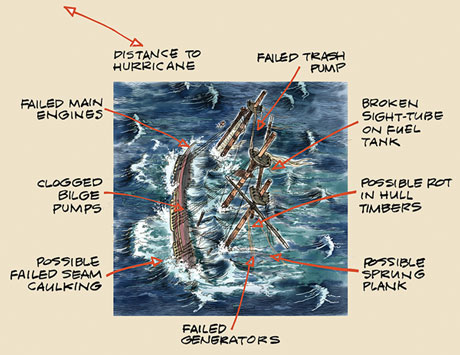

Picture this: The ship was old, very old. Although she was tired and undercapitalized, she had recently been through an extensive shipyard visit, and a number of issues had been addressed. Arguably, she was in better shape now than she had been in a long time. Still, there was the possibility of issues emerging—issues that can always show up after a shipyard visit. There could be pump-clogging sawdust and shavings in the bilges. There was the possibility that something didn’t get put back together correctly, or something didn’t get tightened properly. This is always the case after a shipyard stay.

She got underway in a bit of a hurry, and she was short-handed. The average experience level was low: The crew consisted of a few with some experience and a few with little or no experience.

The long-range weather forecast was poor, even terrible. But the immediate forecast was for the wind to be favorable, and it was hoped that she could make a lot of miles early on, and then stay ahead or out of reach of the worst of the storm. Even if she did encounter the severe weather, the captain was confident that he and the vessel had been in worse conditions, and felt comfortable that they both could take it.

The second mate was a recent maritime academy graduate with some experience under sail and some in commercial vessels. He was comfortable at sea, but had very little experience in square rig. He was fairly new to the ship, so didn’t feel inclined to question the decisions being made by the captain. He knew the weather was going to be bad, and somewhere inside he was questioning the decision to sail, but he wasn’t about to doubt the person in charge.

The ship sailed, and it wasn’t long before the weather deteriorated. A sail or two blew out and was wrestled in and secured. The bilgewater level began to rise as the ship began to work hard in the heavy seas, and the pumps were working equally hard to keep up. At some point the electric pumps failed, and it was uncertain whether or not the backup pump was keeping up. Things gradually were going downhill, and the crew was getting tired. They were also getting wet as the bilgewater began slopping up into their bunks from inside the ceiling planking. The decks leaked as they always did, and in spite of the crew having lined their bunks with plastic, most of the their gear was soaked, making meaningful rest even more difficult.

Then a crew member got injured, seemingly significantly. Now not only was one crew member down, but another had to attend to him. Resources were draining away fast.

The name of the ship was the REGINA MARIS. The year was 1981. And I was the second mate. We made it to Bermuda, but not a moment too soon.

I kept a journal on the trip I just described, and reading it now is just as eerie to me as my account above likely is to anyone who has followed the BOUNTY tragedy. While following the U.S. Coast Guard hearings on the sinking of the BOUNTY, I was haunted by déjà vu. During every hour of testimony I wondered, “Why didn’t they speak up?,” and “That sounds so familiar.” Right up to the moment that BOUNTY’s captain decided it was time to prepare to abandon ship, I can say, “I’ve been there.”

Yet we didn’t get to that point, and as a result I learned little. There was no traumatic stress, there was no press, there was no hearing, there was no public outcry, and there was no analysis. I always thought I had gained experience. Nietzsche said, “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” That may be so, but we have extrapolated that to mean that such experience also makes you smarter.

Not necessarily. My experience on REGINA didn’t make me much smarter, but it did make me bolder. The next time the forecast was bad I could say, “I’ve seen worse.”

I knew two of BOUNTY’s crew, and I knew her captain, Robin Walbridge. The two crew had been students of mine, and Robin was as kind and earnest a teacher as I have ever met. This tragedy hit me hard, and like a lot of people, I needed to find out what went wrong. I teach professional sailing at Maine Maritime Academy in Castine, Maine, and I needed to know what to tell my students about this accident. I wanted to extract the experience from it and pass it along.

——◊——

On October 25, 2012, with Hurricane Sandy northbound over the Bahamas and already being dubbed either the “Superstorm” or the “Frankenstorm” by the national media, the tall ship HMS BOUNTY put to sea from New London, Connecticut, and headed south. The 50-year-old wooden ship, built as a movie prop, sailed almost directly into the storm and sank with the loss of two lives: the captain, Robin Walbridge; and one deckhand, Claudene Christian.

BOUNTY was sailing not as a U.S. Coast Guard–inspected Sailing School Vessel, but as an uninspected Dockside Attractions Vessel. As such, paying visitors were allowed aboard at the dock, but none were allowed to go to sea in her. Her voyage crew had to be composed of paid professionals and volunteers. In this case there were some of each, but only a few had significant offshore experience in this type of vessel.

Experience

Experience in a vacuum doesn’t make us smarter. Experience has to be processed. It has to be considered with full disclosure. Perhaps writing in my journal accomplished some of that for me, because over the years I have gone back and reread that journal and appreciated how close we came. But that was nothing like what a serious debriefing might have accomplished. Whatever thoughts I may have had never got compared to and complemented by the thoughts that others onboard may have had. We all could have learned a lot from that trip, but I think we just got bolder.

Much of the evidence I heard in the BOUNTY hearings tells me that Capt. Walbridge had gotten bolder. On the last day of testimony, the chief mate described a previous trip south in November when they sailed into the convergence of two northeasters and encountered winds and seas that were worse than what they saw in Hurricane Sandy. They suffered enough mechanical and structural failures in that storm to put them in about the same position I was in aboard the RE-GINA MARIS.

The mate went on to say that when he did, in fact, question the captain’s plan to sail toward Sandy, the captain replied that he had seen worse than what was forecast, and it would be okay. I guess he had learned what I had learned from my “experience.” We can take it. We’re stronger now than we ever have been.

——◊——

Word of BOUNTY’s departure from New London spread quickly on the Internet, and observers tracking the ship’s progress on this magazine’s online Forum were shocked, even scared, by what was happening. Even before the distress call was made, 50 posts chastised Capt. Walbridge for his decision to put to sea and worried that there might be a tragic outcome; nearly 800 additional posts discussed the aftermath of the sinking.

Bridge Resource Management

In the old days the captain held all his cards close, and information about the coming voyage was given out on a need-to-know basis. The mates and the crew obeyed unquestioningly, and if necessary they would be expected to put their lives on the line for the safety of the ship.

But these aren’t the old days. Now there’s a new model called Bridge Resource Management (BRM, also known as Bridge Team Management). Today the captain is taught that his or her crew has useful information and experience of their own to contribute to the planning and decision-making process. Now, crews are expected to do what is required of them to the extent that it doesn’t put them at significant risk of injury.

BRM is required to be studied by all who wish to be internationally licensed seamen, because it has been recognized that several heads are much better than one. The crew (or typically the officers) are expected to have done a share of the work to prepare for the passage, including reading relevant Coast Pilots and Sailing Directions, laying out courses, calculating tides and currents, and checking both the short- and long-range weather forecasts. (The specific tasks are delegated by the captain.) When done properly, this Bridge Team can amass much more useful information than any captain ever did alone. The decisions are then made by the captain, but with a great deal more confidence.

So we train our new ships’ officers to be a contributing part of a team. But do we then hold them responsible for the decisions of the captain? Is the captain now just the president of a democracy? That can’t be. The officers must be allowed, and encouraged, to contribute, and they should be allowed and encouraged to express their views, but in the end it must still be the captain’s responsibility to make the decision, and he or she has the right to expect officers to support that decision…

…until those officers (and possibly the crew) feel that there is an inherently unsafe situation. It is a catch-22. You must contribute to the decision. You must expect the captain to make the decision. You must support the decision. But then, if you think that decision is dangerous, you must do something. And if doing something means refusing to sail, that could be defined as mutiny. It’s a difficult spot to be put in. How do we train people to walk that line?

It requires a culture of professionalism and mutual respect, and that is much harder to teach than Navigation and Rules of the Road. An officer providing advice to a captain must have some tools to work with. One of those tools is referred to in a BRM course as a “shared mental model.” You all should be thinking along the same lines, aware of the same plan, sharing the same goals and strategies for reaching those goals. Then, when reality is veering from the plan, you are empowered and expected to speak up.

On BOUNTY, the goal was a voyage to St. Petersburg, Florida. What was missing was a shared mental model of how best to achieve that goal. The second mate had laid out a voyage plan, but that plan had long since been abandoned. The chief mate’s strategy was to avoid the storm, apparently by staying put. The third mate seemed not to be part of the plan. The captain had a strategy that involved toughing it out and sailing near, or even through, the storm. As a team, there was no common vision of the coming voyage. With no shared model, no one could say for certain when the model was failing.

It’s easy to say that when the pumps are not keeping up with the leaks, your plan is failing. But the failure of a plan should be detected before that. The whole idea of BRM is that someone will spot an error chain before it reaches the point of sinking—not at that point.

——◊——

It was Capt. Walbridge’s habit to hold a crew meeting on deck around the capstan before a major evolution to explain what was about to happen and turn it into a teaching moment. He held such a “capstan meeting” just before BOUNTY’s departure from New London, but this time it was by request of the chief mate, who was concerned about the decision to sail, given the forecast. He felt that the crew deserved to hear about the upcoming weather and be offered the opportunity to stay ashore.

Risk Assessment

Every voyage carries a degree of uncertainty. In everything we do, and even when we do nothing, we assume a level of risk. So we manage risk every day. But when we are in a position where we are managing other people’s risk, especially when we are engaging in activities that carry significantly elevated levels of risk, it pays to get more organized about it.

The U.S. Coast Guard knows a thing or two about risk. Many of their tasks involve substantial risk, and as a result, they have produced a formalized Risk Assessment Model that is employed before any significant evolution, such as a voyage. I have adopted and simplified that process into a hypothetical re-enactment of the BOUNTY capstan meeting on the day of departure from New London. It could have gone something like this:

Captain to assembled mates, engineer, and bosun: “Okay gang, tell me what you know about the state of readiness of your department. We’re talking about a 10-point scale here.”

Bosun: “We’ve recently left the shipyard, so there is always a possibility of issues related to shipyard work. Detritus in the bilges, overlooked issues of tightening things, missed fastenings, that sort of thing. Since we have made a short voyage already, we are reasonably confident that all is well, and the vessel seems to be taking on less water than before. However, when we removed those planks for inspection we found a significant amount of rot, and we were unable to ascertain how widespread it was. It is possible that we have a significant structural problem, but we don’t know. We also did a substantial amount of recaulking and were uncomfortable with some of the seams we worked on. I would take a point off our preparedness scale for these conditions.”

Engineer: “We seem to have some problem in the bilge pumping system that we haven’t identified. We may be pumping at a slower rate than before, and we are having a more difficult time keeping a prime on the pumps, and we don’t know why. The two hydraulic backup pumps and the gas trash pump have not been tested in a long time. All of our generating and propulsion equipment is old, but seems to be working well. We have a problem with spare fuel filters due to having received the wrong ones. I would have to take a couple of points off for the pumping issues, unless we test those spare pumps, ascertain their effectiveness, and teach everyone to use them.”

Third Mate (Safety Officer): “We have several new crew who have not participated in a fire or abandon ship drill yet. We have a relatively small crew, and all are pretty tired after the busy schedule of the past several days and weeks. The net level of experience on the vessel is relatively low at this time. I would have to take a point off for tired crew and inex-perienced crew, since they complement each other negatively.”

Second Mate (Navigation Officer): “The voyage plan I laid out is no longer viable due to Hurricane Sandy. I have not laid out a new plan, but the captain has determined that a route out to sea to the east and south will give us the best options. I have not evaluated that plan, and I am unfamiliar with the forecast for Sandy. I would have to take a point off unless I have time to evaluate the forecast and the proposed route.”

Chief Mate: “I concur with all the reports above. Due to the forecast for Sandy, it is reasonable to expect that we will encounter rough weather (possibly very rough) on this passage. A best-case scenario would have us skirting wide of the storm’s reach but still feeling the effects that surround a hurricane, namely large swells and some wind. In the worst-case scenario we could expect gale, storm, or hurricane-force conditions. Given the potentially severe weather, the concern about rot and possible bad seams, the questionable state of the pumps, and the tired and inexperienced crew, I need to take another two points off for a convergence of issues.”

Captain: “This brings us to a score of 3 out of 10. This demonstrates a very low level of preparedness, or a high level of risk. We must weigh that against the need to sail. Our need to sail is based on our desire to keep to our schedule of having a port visit in St. Petersburg next week. That could be rescheduled without a great deal of difficulty or loss of revenue. How do you think we should proceed?”

The advantage of this kind of an assessment process is that everyone sees their own issues in the context of other issues they may not have been aware of. If each department head thought theirs were the only issues, they may well have been lulled into complacency. But seeing all the issues in one basket gives everyone an appreciation of the sum total of all the various risk factors. In that light, a captain would have needed a very compelling reason to sail, which seemingly did not exist on October 25.

This process also provides a basis for mitigating the risks going forward. What was just laid out in the hypothetical discussion above was a work list to get the vessel ready for sea. The ideal response to the captain’s final question would have been something like this:

“Let’s locate the best possible storm berth, batten down for a possible storm here, and give everyone some rest. Then let’s find the problems with the bilge system, exercise the backup pumps (using that opportunity to train people in their use), get those spare filters, and conduct some drills. While we’re at it, let’s do some hurricane avoidance plotting as a learning experience.”

It is important in this process to avoid getting fixated on numbers. This is not a precise mathematical model. Whether you take off one point or three, the idea is to talk about it and make everyone aware of your concerns, in the context of everyone else’s concerns.

——◊——

Earlier in the month of October 2012, BOUNTY had completed a substantial shipyard period in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. In the course of that yard period, the crew had removed a few planks from each side of the hull to investigate a suspect area. What they found was a surprising amount of rot, considering that that portion of the hull had been rebuilt only five years earlier. This raised questions that did not get answered. Due to time and financial constraints the decision was made to put her back together and take a closer look at the next yard period in a year or two. During the U.S. Coast Guard investigation of the sinking, there was a difference of opinion between the yard foreman, the yard owner, and the surveyor over whether that rot might have been structurally significant. The most that can be said at this time was that there might have been a problem.

Also, while underway from Boothbay to New London, several of the crew commented that the bilge pumping system was not pumping at full capacity, and it was difficult to maintain a prime. Similar to the rot issue, the cause of this problem, or even the existence of the problem, was not determined before departure from New London.

Margins of Safety

Margins of safety are built into almost everything. We buy a piece of line two or three times stronger than its assumed maximum loading requires, so it can chafe halfway through and still hold. We buy an engine with three times the horsepower needed to move the ship at speed, so that when we are caught in a foul current or strong wind and are losing control we have that extra power to push us to safety. We buy an anchor four or five times the size we need to prepare for that day when everything goes against us and a big anchor is all we have left. Then we avoid areas of danger by a wide margin, so if something goes wrong, we have time to come up with a solution before we’re in peril. Much as in risk assessment, you can’t appreciate how much of your margin of safety you have used up without evaluating all the contributing factors.

BOUNTY was massively built. She could be half rotten and still be strong. Her bilge pumping system was designed with no fewer than four separate pumps, any one of which was expected to be sufficient. Then, just in case, another was put onboard as a spare. Numerous spare fuel filters were purchased, even though one was all that was theoretically needed. She had two main propulsion engines, and two generators, each of which was sized larger than necessary. The voyage plan stipulated a first leg to the east to gain sea room and to allow a turn farther east, or a turn west, as the track of the storm became better established.

All of the above provided the kind of margin of safety that we take for granted. It not only keeps us from sinking, but it keeps us from getting near that point. That separation is the cushion between us and disaster.

The rot that was discovered in the shipyard may have been significant, or it may not have been, compared to the overall strength of that massively built hull. But its existence, and the suspect nature of some of the seams, whittled away a little at the margin of safety.

On the voyage to New London, the bilge pumping system seemed not to be pumping at capacity, and it was difficult to keep the pumps primed. Furthermore, many of the crew were unfamiliar with the operation of the hydraulic-driven pumps, and apparently no one was familiar with the operation of the trash pump. Combined, these took a large bite out of her margin of safety.

The spare fuel filters that arrived turned out to be the wrong ones. In the end they seemed to work, but required careful attention to keep them from clogging. Another slice gone from the margin of safety.

The two engines and two generators may have run fine, had not the day tank’s sight glass broken and drained away their fuel. Unfortunately, all that spare engine capacity had a common link, and it broke. The margin of safety at this point was whittled down to a hair.

Still, they likely could have made it if only they had stuck to their original margin of safety in terms of intended track. Had they not been so close to the storm by the time the engines and generators failed, they might have given the Coast Guard time to deliver some pumps, or to repair their own equipment.

Much like the risk-assessment process, you must be able to assess and evaluate all the things that make up your margin of safety, and acknowledge each failure of equipment or loss of function that chips away at it. It is critical that they be viewed in sum, not in isolation. If each person is aware of one issue, but nobody puts all the issues together, no one will appreciate the seriousness of the situation. It is a proactive process, not a reactive one. You must build in safety margins deliberately, and recognize them when they fall away.

——◊——

As the ship was sailing from New London, a message was posted to the BOUNTY’s Facebook page: “BOUNTY has departed New London CT...Next Port of Call...St. Petersburg, Florida. BOUNTY will be sailing due East out to sea before heading South to avoid the brunt of Hurricane Sandy. Rest assured that the BOUNTY is safe and in very capable hands. BOUNTY’s current voyage is a calculated decision...NOT AT ALL... irresponsible or foolhardy as some have suggested. The fact of the matter is...A SHIP IS SAFER AT SEA THAN IN PORT!”

To Sea or Not to Sea?

It used to be an accepted standard that a ship was safer at sea than in port in the event of a severe storm. That is, in fact, still true. However, it used to be that the ship was more important to the owners than its crew was. Nowadays, our priority is to protect the crew first, and the ship second. This may require staying put even though the ship herself is threatened.

Still, it is an oversimplification to say that no one should leave port when there is severe weather in the forecast. There will be times when a ship is in an untenable situation in a poorly sheltered port, with no good alternatives within reach. When that is the case, everyone in the Bridge Team should be made aware of it from the time of arrival, so all can keep a weather eye out. Then when a storm is forecast, the decision can be made in time to permit a safe departure that will allow the ship to gain sufficient sea room to weather the storm with an adequate margin of safety. In that case, the ship will in fact be safely out to sea.

We can’t distill these decisions down to a simple checklist. They need to be made based on a weighting of risk versus necessity, and they require experience, maturity, and judgment. If the principles of Bridge Team Management and Risk Assessment are employed, the captain should be able to make an informed decision that balances the risk of sailing against the risk of staying put.

——◊——

By Sunday afternoon, the situation onboard was getting out of control. Something caused a sight glass on the day (fuel) tank to break, which in turn drained the fuel from the tank so the engines and generators ran out of fuel and died. Because they were diesel engines, their fuel systems must be bled before restarting, a tedious process on a good day, never mind in a 100-degree engineroom that was rolling heavily enough to upset even a strong stomach.

Bilgewater levels were rising steadily, and even though the second mate, through heroic efforts, managed to get a generator re-started, the pumps were clearly not keeping up. It wasn’t long before the rising bilgewater overtook the last running engine, and they were left without power. The chief mate suggested to the captain that it was time to make preparations to abandon ship, and after briefly resisting that idea, the captain did come to terms with the inevitable and ordered all hands to start donning survival suits and assembling on deck. A lingering question remains: Should that decision have been reached 6, 12, or 24 hours earlier?

Denial and Acceptance

An automobile accident happens so fast it’s probably over before you know it’s happening. If you wake up to find your house on fire, you don’t take long to figure out what’s going on. But a ship sinking at sea can be a slow process, and unless there is a catastrophic failure such as a major collision, you may be gradually overcome by events and it may be difficult to identify the moment when things have gotten out of hand.

They certainly did on BOUNTY. It’s particularly telling that no one, in testimony, talked about feeling fear. The disaster slowly caught up to them, and suddenly they were awash. In a situation like that you must accept the possibility that things are getting out of hand as early as possible. At sea, help is a very long way away, and the earlier you can give notice the better the odds will be for help to reach you.

It is human nature to deny that things are that bad. The consequences of acceptance are awful to comprehend, and so we shy away from it. To pick up the radio and call the Coast Guard tells your crew that they may end up in the water soon, that their lives may truly be in jeopardy, and that the ship you have known, loved, and nurtured for so long may be about to vanish forever. It also tells people on shore that their loved ones are in a life-threatening situation with no guarantee of a safe outcome. Who wants to make that call prematurely?

In hindsight, and in the classroom, it’s easy to know exactly when to take that step. But in the moment it can be very hard. The good news is that there is a mechanism to make it easier: the PAN-PAN urgent message format. These words, spoken on the VHF radio or sent by any other method, tell the recipient that you are in a difficult position, but not desperate yet. It allows you to get the attention of the people who can help without your having to declare a MAYDAY, which means that you are in a life-threatening situation right now. Having the PAN-PAN message option encourages you to get past the denial stage as early as possible and accept that you have a potentially dangerous situation on your hands. So alerted, help can be ready before it’s too late.

Onboard BOUNTY, there may have been some disagreement about making the first call to alert the Coast Guard. As before, it would have been useful to take a Bridge Team Management approach, and a Risk Assessment approach, to evaluating the situation. It is much easier for a single person to remain in denial (as it appears the captain may have been) longer than a group. If the team were assembled and polled for the state of their respective departments, the picture may have been clearer, earlier.

——◊——

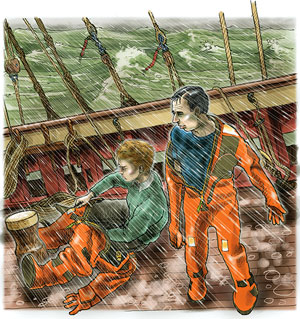

The crew was finally instructed to muster on deck, don their survival suits, and prepare to abandon ship. Unfortunately, before an orderly abandonment could occur, the ship rolled heavily onto her side, throwing the crew variously into the water or onto the rig, which was now lying in the water.

Transition

It has been said many times that “the time to abandon ship is when you have to step up into the lifeboat.” Like most clever catchphrases, this one has its limitations, although it also has some merit. The idea is that you should never leave your ship until she is really, truly sinking because no matter how well equipped your lifeboat is, it isn’t as well equipped as your ship. There are, indeed, many tales of ships found drifting whose crews abandoned them, only to vanish with their lifeboats.

Unfortunately, one good phrase can’t fit all situations. On BOUNTY it suddenly became very clear that they should have abandoned ship a little earlier. You do need time for an orderly transition into your lifeboats or rafts. The way BOUNTY went down demonstrated all the problems that can accompany a last-minute transition.

BOUNTY lost stability as she filled, and finally rolled onto her side, throwing many of the crew into the water. Some who were still onboard became tangled in gear, and some were either tangled in or clinging to the spars that were now in the water. Unfortunately for them, the ship rolled partially upright again, dragging them up into the air. They were then forced to jump into water that was now filled with debris that was being violently tossed around by the breaking seas.

Among those who were thrown into the water, many were beaten with floating debris, or by blocks and other gear falling from the rig. Two crew members clipped their harness tethers together to keep from being separat-ed—seemingly a good idea. However, a heavy piece of the rig fell into the water between them, trapping them and dragging them down by their tethers. They were well underwater before one of them miraculously managed to free himself from his harness. The buoyancy of their survival suits was so strong that they were unable to release the clips on the ends of their tethers. A quick-release clip on the near body-end of a tether should be universal standard equipment. Curiously, it is a requirement on offshore racing yachts, but that detail has not yet made it into the mainstream of survival and harness technology.

With the ship on her side, the nettings that had been set up to keep crew from falling overboard now kept them from getting away. Several of the crew talked about feeling the suction of the water pouring into the ship; they had great difficulty swimming away from the ship because of it. Combine that with the general difficulty of swimming in an immersion suit, getting washed by breaking waves (making breathing difficult at best), and you have a terrible situation.

All of the above tells us that, in your abandon-ship drills, you should at least talk through all of these issues and plan where the best assembly point is on deck. Many drills have people muster amidships where the crew is most “protected.” But the BOUNTY’s lesson tells us that the well deck amidships may have been the most vulnerable spot because it left crew trapped between nettings and under a towering rig about to start falling down. In the BOUNTY’s case, with hindsight, the best muster point would have been as far aft as possible.

The salient point is not that one place is always better, but that the abandonment process should be thought through considering the type of vessel, rig, and rescue platform available. It could be different under different conditions.

When you consider the amount of chaos surrounding a capsized or flooded ship, especially a sailing ship, you must think about the amount of line and other gear floating on the surface on and around the ship. Many crew found themselves becoming tangled again and again while trying to get away from the ship, and even while trying to climb into the life rafts. This begs for the installation of a knife on the outside of a survival suit as part of the standard equipment. It should be a blunt-tipped knife to avoid injuries, but it should be sharp, with a serrated edge capable of swiftly cutting a person free of entanglements. Bear in mind that the knife must be of a size and shape that a person can use while wearing the survival suit gloves or mittens.

With a knife available, one could also solve another problem that cropped up when the crew was trying to board the rafts. Their suits were partially filled with water, which of course ran down to their feet when they tried to climb up, or were pulled up, into the raft. With a knife, one could slash the foot of the suit to drain the water out. Better yet, the suit could be manufactured with a drainage zipper in each foot.

——◊——

Very fortunately, the Coast Guard had been notified in time for them to fly a C-130 Search and Rescue aircraft to the scene, through darkness and hurricane-force winds, to monitor the situation and maintain a communication link. Even though they could not rescue the crew themselves, through a prearranged signal they were able to learn when the crew was finally thrown from the vessel and call for the rescue helicopters. The helicopter crews later stated that these were the worst conditions they had ever flown in.

Through truly heroic efforts and no small amount of good luck, these extraordinary people were able to fly to the scene and drop a rescue swimmer into that maelstrom to find and then lift the crew one-by-one to safety aboard two helicopters. Tragically, two BOUNTY crew members were missing, and as fuel on the helicopters was running low, the Coast Guard crews were forced to make that most difficult decision of all and leave the area to fly back to shore.

But they didn’t stop there. They came back out again as soon as possible and continued the search. They did manage to find one missing crew member, Claudene Christian, but she was pronounced dead on arrival ashore. The other missing person was Capt. Walbridge. He was last seen either on deck or at the navigation station, in a survival suit, but after two days of searching he was not found.

After

Finally, the crew was rescued and walking on dry land. It was not the end of the story. In many ways, it was just the beginning. There would be media attention, a U.S. Coast Guard hearing, post-traumatic stress, complicated group dynamics, and the terrible grief surrounding the loss of their captain and shipmate. The depth of their agony can only be understood by talking to the crew and seeing it in their eyes. They had lost, variously, a shipmate, a friend, a lover, a mentor, a father figure, and their captain. That loss would creep up on them and affect them in different ways, but it was universal.

The extreme difficulty of these first several days is difficult to imagine. The crew was, to varying degrees, traumatized, stunned, cold, wet, injured, sick, or just plain confused, and there were a lot of details that needed to be taken care of immediately. They needed rest, food, new clothes, identification, medical attention, cash, a place to stay for the short term, and travel arrangements after that. They also needed advice on dealing with the media and the flood of attention, wanted or unwanted.

To provide all of the above on very short notice, a vessel’s home office needs to be prepared, and that preparedness can only be achieved by having a carefully thought-out Crisis Response Plan. Such a plan will also guide the principals of the organization. Imagine being woken from a sound sleep with the news of such a terrible tragedy, and immediately being asked to provide a long list of information, such as: crew list, contact information for next of kin, insurance information, and a media plan. You will face that terrible task of calling the families of the crew, including perhaps telling parents that a son or daughter is dead or missing. You might be asked for stability information, the ship’s plans, an inventory of survival equipment and communications equipment, and vessel tracking data. The list goes on and on, and it may still be the middle of the night.

If you haven’t ever planned for this kind of event, and actually practiced it by conducting an emergency drill, you may be instantly overwhelmed and project to the world an image of disorganization and incompetence. That could shift the media’s attitude from one of sympathy to hostility very quickly, especially if in your groggy, panicky state you start saying things that don’t come across as professional.

It is important to understand that once the rescue is concluded and all the lives that can be saved have been saved, the function of the U.S. Coast Guard shifts from rescuer to investigator. The purpose of the investigation is a positive one, but it will be very strenuous nonetheless.

The Coast Guard conducted interviews within a day or two of the rescue to try to get as much of the story as possible written down correctly before memories faded. And memories do fade. They also get muddled with other information that might not actually be a memory. This can lead to embarrassing testimony when the hearings finally get underway, since it may appear that you are contradicting your own testimony. One of the crew stated at the beginning of her testimony (at the hearing) that “whatever I told you in that first interview will be much more accurate than anything I can remember today.” That is an excellent point to remember, both for the interviewer and the interviewee.

There is another point to remember: Stick to the facts. This applies to your comments to the Coast Guard, to the media, and to the lawyers. Don’t editorialize. Don’t give your opinions. If a sentence begins with “I think,” it’s probably not a good one. If it starts with “I saw,” or “I heard,” it’s better. Remember this: Whatever you think today will quite likely change by tomorrow. There are always at least two sides to every story, and over time you may come to realize that what you thought was not how it happened.

After an accident, some people always blame someone else, and others always blame themselves; most of the time they will both be wrong. Very few accidents have a single cause. If an investigation takes place, it will take time, but it will ferret out the whole story, to the extent possible. Keep your mind open; be prepared to learn that it didn’t actually happen the way you thought it did.

As much as you should keep your opinions to yourself, there is an exception. Sharing all your thoughts with someone who can understand what you’re talking about, and will keep it private, will help you cope with the emotional burden you are carrying. That might be a professional counselor, or it might be a close friend who knows something about the subject. If you think you are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, or if someone else tells you they think you are, you should talk to a counselor who specializes in that. PTSD is a serious condition, and the worst thing you can do is deny it. There are strategies for learning to cope with it.

There will be people who will criticize and perhaps condemn you, or someone close to you, for the accident. People are quick to jump to conclusions, and they are often encouraged by the media to do so. Somehow you need to steel yourself for that, and shelter yourself from it as best you can. Avoid getting drawn into the conversation. Remember, you don’t know the whole story, and they know almost none of it. That combination cannot possibly be productive.

Experience, Revisited

To the extent possible, we all must learn from the BOUNTY’s sinking. That is the point of a Coast Guard hearing. The lead investigator of the BOUNTY hearing started each day with a statement that the purpose of the hearing was to learn from the accident, to see what steps might be taken to prevent something like it from happening again.

The process of dissecting the accident to identify the various root causes is a painful one. It requires reliving the entire event several times while everyone tells their version of the story. It involves uncovering faults and failures in people you know and care about, including perhaps yourself. It’s inescapable that for a bad accident to happen, someone probably failed at something. It’s very rare for an accident to truly come down to an act of God, so prepare yourself for the inevitable and tell the whole story, including the failures, as you saw them. Don’t try to hide them. Let the process work. It will, in the long run, be a healing process. From all of that will come experience.

Capt. Andy Chase is a professor of marine transportation at Maine Maritime Academy (MMA) in Castine, Maine. He began his professional seagoing career at the age of 16 as a deckboy aboard a Norwegian bulk carrier, and is a graduate of MMA. He holds an unlimited-tonnage master’s license for power vessels, and master of auxiliary sail for vessels of up to 1,600 tons. He has sailed aboard tankers, container ships, tugs, freighters, and large, traditional sailing vessels of gaff and square rig. Capt. Chase was the subject of John McPhee’s book about the U.S. Merchant Marine, Looking for a Ship (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1990), and is the author of the textbook Auxiliary Sail Vessel Operations (see below).

![]()

FURTHER READING

Auxiliary Sail Vessel Operations, by G. Anderson Chase (Cornell Maritime Press, 1997). Filling a longstanding void in nautical science literature, this book is an introduction to the fundamental principles and practices needed to work in today’s commercial-sailing industry.

Bridge Resource Management for Small Ships: The Watchkeeper’s Manual for Limited-Tonnage Vessels, by Daniel S. Parrott (McGraw-Hill, 2011). This is the first textbook to teach the concepts of Bridge Resource Management for limited tonnage vessels. Topics include resources integration, situational awareness, passage planning, communication, and other best practices as described in this article. The book also covers the concepts of over-reliance, stress, fatigue, complacency, and leadership. The book’s author is a colleague of Capt. Chase at Maine Maritime Academy.

gCaptain.com. This maritime and offshore news website carried Mario Vittone’s riveting and incisive interpretation of each day of the Coast Guard’s hearings on the BOUNTY sinking. Enter “BOUNTY” into the site’s search tool to see eight BOUNTY-related posts.