The Evolution of the Craft

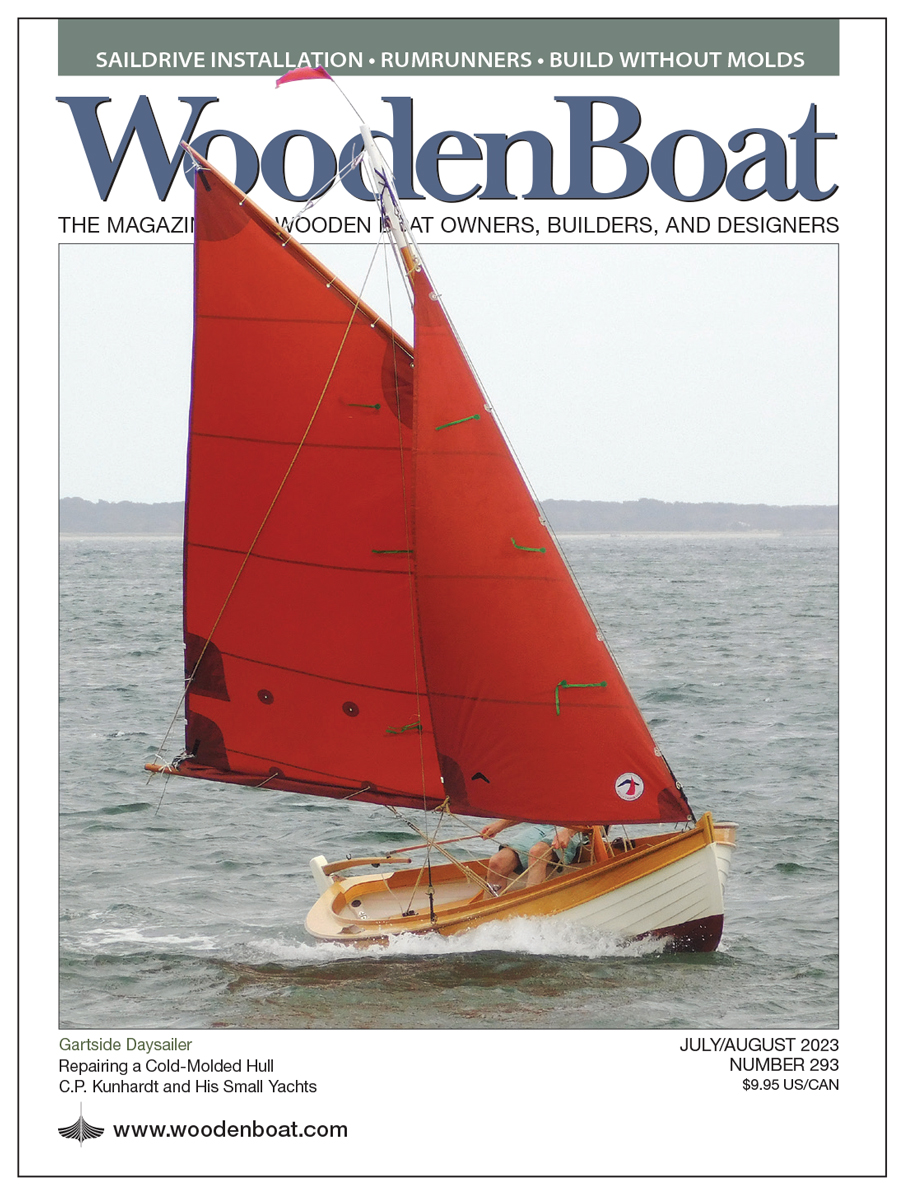

The captivating little Paul Gartside–designed daysailer on this issue’s cover is called Skraeling, and it harks back to a centuries-old Scandinavian design tradition—an inspiration quite apparent in its jaunty-sheered, lapstrake-planked, double-ended hull. And yet it was designed purposefully for modern living: its owner hails from southern California and lives in an apartment. He could not sail the boat from a trailer, and available slips at a nearby marina limited the boat’s size to 14'. The hot climate augured against the demands of maintaining a boat of solid wood. Thus, as we learn in Mike O’Brien’s review of the boat beginning on page 98, Gartside specified lapstrake-plywood planking, glued with epoxy, which would not be ravaged by moisture cycling and would thus tend to hold its hull paint for a longer period than would a solid-wood-planked boat.

The marriage of wood and epoxy also came into play in the restoration of the Fife-designed 6-Meter sloop JUDITH PIHL, but in an unusual way, by the crew at Sydney Wooden Boats in Australia. This job is absolutely stunning in its comprehensiveness—a total rebuilding incorporating largely original materials. As Megan Treharne and Simon Sadubin recall in their article beginning on page 36, this yacht, built in the 1930s, was part of a six-boat fleet of one-design 6-Meters that were active in Australia between the World Wars. JUDITH PIHL was discovered in a rural paddock several years ago, semi-derelict. But she was planked in Huon pine from Tasmania and had a backbone timber of New Zealand kauri; these two species, now rare, are prized for their longevity in boats. It made sense in this project to save them. The boat was thus completely dismantled, and the carefully removed planks were repaired by having their fastening holes plugged and

new edges glued on with epoxy. The keel timber required minor repair before receiving a new set of frames accurately laminated to Mylar loftings.

The newly built peapod whose construction is presented beginning on page 76 followed a similar planking and framing process as JUDITH PIHL—which is to say that there were no temporary molds involved in its construction, and it is planked on pre-bent frames (in this case, steam-bent ones). Wade Smith, author of that article, succinctly summarizes the significance of this project: “Although we in the 21st century think of this as the usual or ‘traditional’ way to build a carvel-planked boat because that’s how most of us were taught, in the late 19th century the most common way of building small, light boats was without molds and using pre-bent frames.”

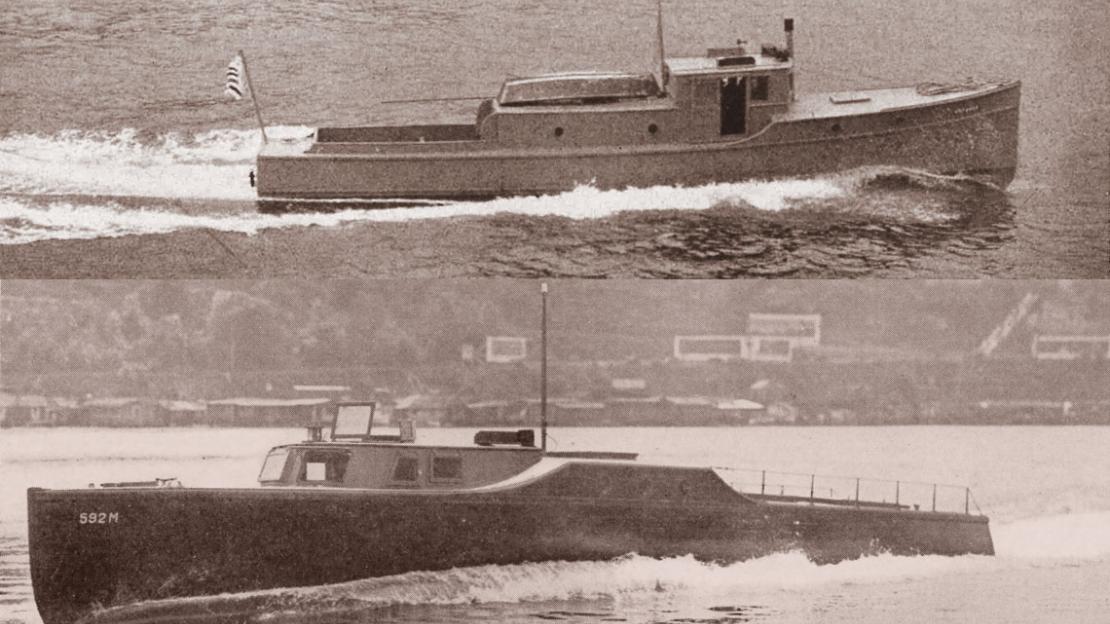

Consider, too, the repowering of PLYM, described beginning on page 88. This project involved the installation of a saildrive unit to power a long-ended, 56' sloop that was originally launched in 1948 with no engine at all. By 2020, she had a centerline, shaft-driven propeller, and had been given a separate spade rudder instead of her original keel-attached rudder—a configuration that, while mostly good, caused an unacceptable pulsing of the helm when under sail. A saildrive, rather than a shaft, turned out to be the only cure, and Nigel Sharp describes that careful marriage of this modern unit with a classic hull.

Even after more than three decades at the helm of this magazine, the continued resourcefulness of builders and the constant evolution of wooden boat building and repair continue to amaze me.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine