Lucky Boats

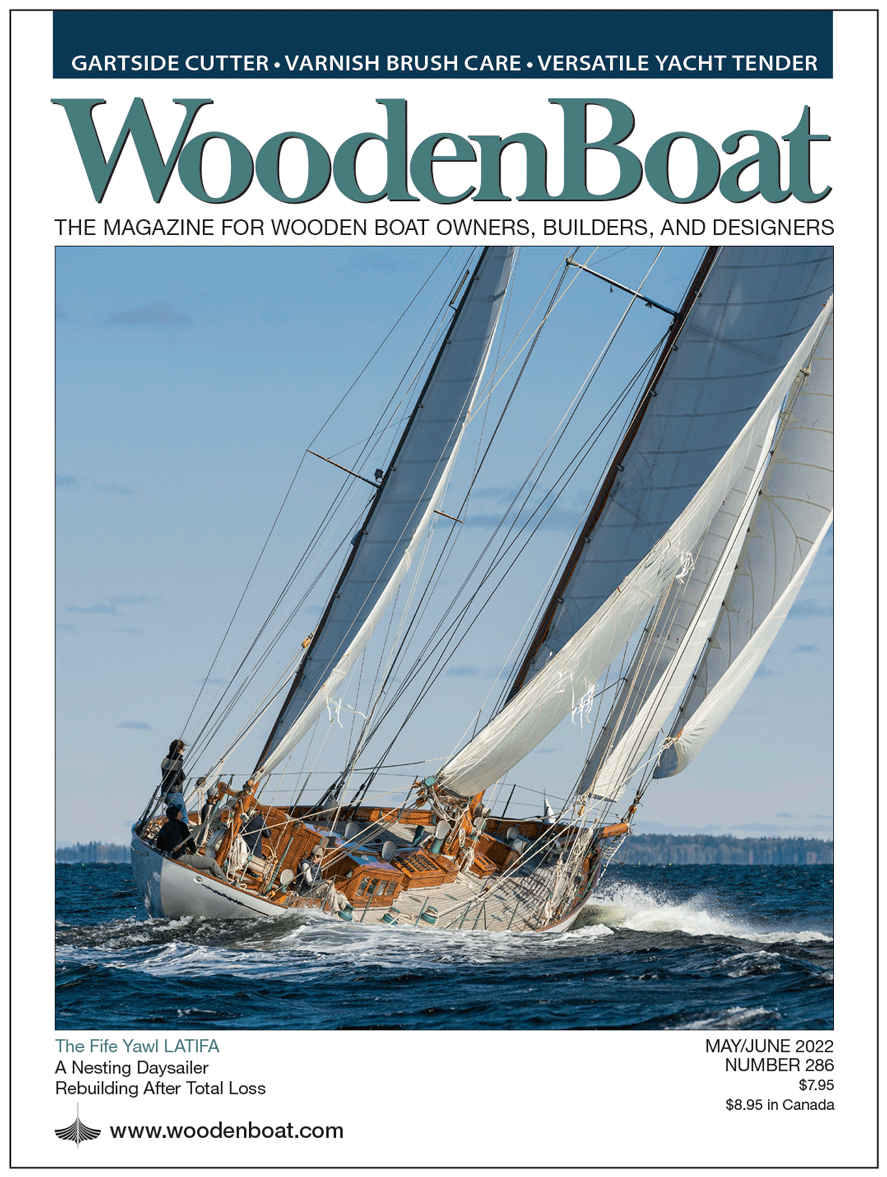

“LATIFA is the lucky one,” said the classic-yacht broker Barney Sandeman. He was speaking about the magnificent Fife yawl on the cover of this issue and featured beginning on page 64. The yacht, designed by William Fife III and built by the Fife yard in Fairlie, Scotland, has been in commission since her launching in 1936. Unlike many of her Fife sisters that were laid up in mud banks during what was a sort of Dark Ages for classic wooden yachts, LATIFA has been consistently maintained, upgraded, and appreciated. Her current owners have made careful upgrades that are sensitive to her originality, and at this writing she is poised to head into the Pacific Ocean, bound for Tahiti and thus continuing a remarkable voyaging career.

Like LATIFA, MESSENGER III, a 75-year-old power vessel based in Victoria, British Columbia, has enjoyed a life of good stewardship. She is one of the few remaining examples of a mission boat, built to serve outposts once scattered along the length of British Columbia’s long, convoluted coast. Tad Roberts, the yacht designer and an authority on British Columbia’s maritime history (his every-other-issue design review appears on page 56), notes that her builder was “decent, but not high-quality….” Their boats, he said, “were built to a price and intended to do a job.” Her longevity, he reasons, is thus due to the exceptional maintenance of a succession of caring owners. The priorities of the stewards of boats such as LATIFA and MESSENGER III are worthy of study and emulation by any would-be wooden-boat owner.

And then there’s CLARALAN (see page 34). She’s the luckiest boat of all in this issue—and among the luckiest I’ve ever encountered. On February 24, 2014, as Bruce Stannard tells us beginning on page 34, she grounded on rocks at Thistle Island, South Australia. The crew, including her designer-builder Andy Haldane, were able to abandon her without injury. What followed would have relegated the boat to the scrap heap, for most owners. Over the next several hours, and before Andy could return with a salvage vessel, the boat rolled onto its side, and in the surging seas the entire starboard side was worn away. His salvage team, reporting on the boat’s condition after diving on the submerged starboard side, reported, incredulously, “it just ain’t there.” The photographs in the article bear witness to this.

Andy’s response to this disaster had the appearance of a Herculean rebuild. But for Andy, we learn, the job was a sort of relaxation—a meditation. While I’m sure he would rather have had his boat for the seven years it took to put her back together again, his answer to the question of what motivated him through the rebuild project will, I’m sure, resonate with many readers of this magazine—even though they may find the scale of the CLARALAN project difficult to grasp. “I’ve been building boats all my life,” Andy said, “and that’s what I love doing. I do it because I want to do it, because I derive a deep-down personal satisfaction from my work.” A lucky boat, indeed.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine