A Pacific Northwest Sharpie For The Bahamas

Around 1991, Jon Eaton (my editor at International Marine Publishing) suggested that I write a book about sharpies. He knew I was a fan of the type (inshore fishing/oystering/crabbing boats), and I gladly accepted the assignment.

I researched the history of sharpies in various museums and historical societies on the US East Coast, from Mystic Seaport to Miami. I already owned many books, pamphlets and government papers about sharpies, especially from marine historian Howard Chapelle.

During one hectic summer in Rockport, Maine, I wrote the text and designed (adapted, really) all the examples for The Sharpie Book. I edited through hundreds of my construction photos, and made additional drawings to illustrate the history and construction of the boats—both using traditional methods and contemporary “cold-molded plywood/epoxy” techniques.

The 19 foot sharpie GATO NEGRO sailing in the Florida Keys.

During the years prior to writing the book, I had designed and built several small sharpies. The first sharpie I built for myself—around 1988—was the 19′ Ohio sharpie GATO NEGRO, which I built in my small boatyard in Islamorada, Florida Keys. Although I have continued to design many more sharpies, both large and small, I had never built and owned a large cruising sharpie myself… until starting to build IBIS in December of 2007.

My shop and office trailer for building the 45′ sharpie IBIS in St. Lucie Village, FL.

Because many waterfront marinas and boatyards along the east coast have been bought and converted into condominiums, it has become increasingly difficult to find a slip for a cruising boat without also purchasing a condo. It occurred to me to create a new design series that I called “Maxi-Trailerable Boats”—shoal-draft sail- and power-boats limited in length to about 45′, 10′ beam, and 15,000 lbs maximum displacement. Vessels of that size can be carried on standard 3-axle 40′ trailers (manufactured primarily for the sportfishing industry). This represents the maximum size vessel that can be transported on federal and state highways with a permit, but without requiring escort vehicles. Using a commercial tow truck, an individual permit is not even required. With tabernacled masts, the rig can be taken down or set up in a matter of a few hours. Thus you could take your cruising boat home with you, or transport her to your desired cruising location.

IBIS completed, on the trailer—centerboard to left; tabernacle A-frame on the bow.

My concept was that you could store and maintain your boat at home (or at an inexpensive storage lot inland) and launch/haul her at a local boatyard using a Travel-Lift or crane, or at a launch ramp using a large four-wheel-drive truck. Thus you could eliminate slip rent and boatyard storage fees, saving several thousand dollars per year.

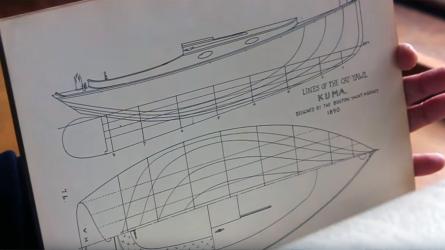

To promote the concept, I decided to build a prototype. I chose the Straits of Juan de Fuca sharpie design for my conceptual “point of departure”, because my design adaptation of the 1880s original (included in The Sharpie Book), seemed like a good choice. These vessels were halibut fisherman—double-ended, gaff-rigged schooners about 36′ in length. Chapelle considered them to be one of the most seaworthy of all the sharpies. The only other popular double-ended sharpie—Commodore Ralph Munroe’s famous EGRET—was from the same time period and also had a reputation for seaworthiness.

Drawing from these inspirations, I created a 45′ sharpie hull, with 10′ beam and 2′ 6″ draft. The hull employed elements of both designs. A big advantage of the long, narrow, flat bottom was that I could employ enough rocker (fore-and-aft curvature) to achieve standing headroom in the cabins. Also, double-ended hulls are often believed to be more seaworthy than other types, and they are “easily driven”, achieving hull speed with a minimum of energy—either from sails or auxiliary power—due to low wetted-surface.

The result was the schooner IBIS, which I launched in early 2010. IBIS was designed to be a live-aboard cruising sailboat, ideally suited to the shallow waters of the US East Coast, the Florida Keys, and especially: the Bahamas.

IBIS anchored off Lee Stocking Island, Bahamas, in two feet of water (aground at low tide).

Although I have sailed several shoal-draft cruisers extensively in the Bahamas, I had never sailed a true flat-bottomed sharpie there. Indeed, I had never owned or even sailed in a large sharpie at all. Hence, in late winter of 2010, I sailed IBIS down the Florida coast to Key Biscayne, across the Gulf Stream, and down through the islands. That first trip was fraught with problems—the heat exchanger broke; one of my inexperienced crewmembers backed over the dinghy painter and pulled the prop shaft right out of its coupling; the pump-out for the holding tank got plugged up; and we had a personality conflict between two crewmembers which resulted in one of them flying home from George Town, Great Exuma. Nonetheless, we had an overall good cruise, and learned a lot about taking a sharpie out in the open ocean.

IBIS handled 4′ to 6′ seas reasonably well on a beat or close reach (she did pound pretty hard at times), and was fantastic from a beam reach to a run. My tactic for achieving “Easting” in the strong Trade Winds was to motorsail under jib and reefed mains’l (or under reefed fores’l alone), pointing as high on the apparent wind as I could. In winds around 25 knots, and 6′ to 8′ seas, I learned to fall off and slow down to seven knots, making 100 degree tacks under double-reefed fores’l and diesel. In wind and seas beyond that, working to windward became impractical, and we anchored in some protected cove or creek to wait for gentler conditions (which is what most people would do anyway).

IBIS under full sail in the Trade Winds; note her ground tackle and side davits.

I took IBIS to the Bahamas three times, and sailed her in many conditions. I was very impressed with her abilities, and realistic about her shortcomings. Overall, I am now convinced that a well-designed and –built big sharpie (with self-righting ability) is an excellent choice for cruising the islands. I did not find myself overly restricted—only the really hard-core sailors will beat to windward in seas over 8′, or winds over 25 knots. Patience is always required in cruising. On the other hand, the ability to sail in less than three feet of water really opens up the possibilities for cruising anywhere! But especially, in the Bahamas, we could explore shallow, seldom-visited creeks, cross tidal flats that dry out at low tide, and access hundreds of safe, quiet, remote anchorages that very few other boats could even dream about!

In late 2013, I sold IBIS to a 60-year-old New Jersey surfer. He is presently cruising in the Florida Keys with her, which I never found time to do. She is the perfect boat for it! I miss her badly, as sailing to the Bahamas has been the high point of my life for almost 35 years now—I love it more than words can express. I am going to have to build another boat….

Sailing from the Banks into Exuma Sound at Leaf Cay, Bahamas.

2/20/2014, Saint Lucie Village