Two Gambles

The birth and survival of the Atlantic class

The birth and survival of the Atlantic class

Rosenfeld Collection, Mystic Seaport

“A good fun boat,” very popular with younger sailors, the Starling Burgess-designed, Abeking & Rasmussen-built Atlantic Class received an added boost when parachute spinnakers were introduced in the mid-1930s.

Edwin Levick Collection, The Mariners’ Museum

Crewed by her designer (in the broad-brimmed hat), the prototype Atlantic sails on Long Island Sound. By 1930, 99 Atlantics were racing in 13 fleets from Long Island to Maine.

The 1920s were a boom time for all Americans, but especially sailors. In the thriving economy, old waterfronts were converted from commercial ports to yacht clubs, many of them devoted to the new idea of junior sailing with equal opportunity for girls and boys. One of the best-known young sailors of the time was Lorna Whittelsey Hibberd. A graduate of the junior program founded in 1924 by the Indian Harbor Yacht Club in Greenwich, Connecticut, in her teens and twenties she won five national women’s championships for the Adams Cup and many other prizes as well against sailors of all ages. “All summer we mostly sailed,” she recalled many years later in an interview with Mystic Seaport’s oral historian, Fred Calabretta. “We used to go down the Sound. We would sail down and sail back, which horrifies people now because they either get towed, or always start off American or Larchmont [yacht clubs]. It was good fun because we learned a whole lot that we never would have learned [otherwise].” There weren’t many days off, she added. “You had to go to church. The sailors didn’t all go to church.”

Sailors like that were, and still are, drawn to challenging boats, and if anyone was eager to create such a boat, he was Starling Burgess. When Burgess turned 50 in 1928, his career as a yacht designer was reaching a new peak of activity and success. As Llewellyn Howland III writes in his recent biography of Burgess, No Ordinary Being, the radical staysail rig that pushed NIÑA, the schooner of his design, to victory in that year’s Transatlantic and Fastnet races, “offered the yachting world dramatic evidence that Starling Burgess was ready to move from the regional onto the national and indeed the international stage.” The Burgess-designed M-class sloop PRESTIGE, meanwhile, was winning armfuls of trophies on the New England racing circuit for her owner-skipper Harold Vanderbilt, who in his careful way was developing the relationship with Burgess that led to three AMERICA’s Cup victories in the 1930s.

Rosenfeld Collection, Mystic Seaport

Five-time winner of the Adams Cup for the national women’s championship, Lorna Whittelsey Hibberd (right, stopping a spinnaker) was an early Atlantic Class star along with Bus Mosbacher and Bob Bavier.

Heading the New York naval architecture firm of Burgess, Rigg & Morgan, Burgess brought four strengths to the drafting table. One was his lifelong experience with boats; the more original they were, the better. Another was his brief but intense engagement with the new field of aerodynamics as a pioneering airplane pilot, designer, and builder—experience that gave him a head start with lightweight construction and the newly popular marconi rig. His third strength was his willingness to take chances, which he did with aircraft and many boats.

Burgess’s fourth strength in 1928 was more pedestrian than the other three: his business relationship with a capable, ambitious boatbuilder. At a time when most sailboats were small or built either one-off or in limited numbers, Henry “Jimmy” Rasmussen was thinking big. The Danish-born head of Abeking & Rasmussen, in Bremen, Germany, he had been in the Western Hemisphere yachting market for several years. At first his plans were modest—for example, when in 1924 he sent over some dinghies for junior sailing programs that were beginning to spring up at yacht clubs on the U.S. East Coast. Two years later, Rasmussen and Burgess collaborated on a somewhat larger project when they developed a class of keel one-designs for the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club. And then Burgess and Rasmussen raised their sights: From 1927 through 1930, they together designed and built a total of 150 boats for American sailors.

They started in a dramatic fashion with fleets of one-design International 8-, 10-, and 12-Meters—a total of 31 boats, with overall lengths from 50′ to 70′. Owned by Clifford D. Mallory and other leaders of the rapidly developing sport of amateur yacht racing, the big meter-boat fleets attracted wide attention, and not only for their tight racing. Shipped to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in order to avoid U.S. duties, they were then sailed across open water to the American East Coast. These voyages both proved the seaworthiness of the controversial new marconi rig and provided offshore experience for several young sailors. One of those youthful initiates was 19-year-old Olin Stephens, who a decade later teamed up with Burgess to design Vanderbilt’s J-boat RANGER. (Stephens later revealed that the towing tank model on which the design was based was Burgess’s work.)

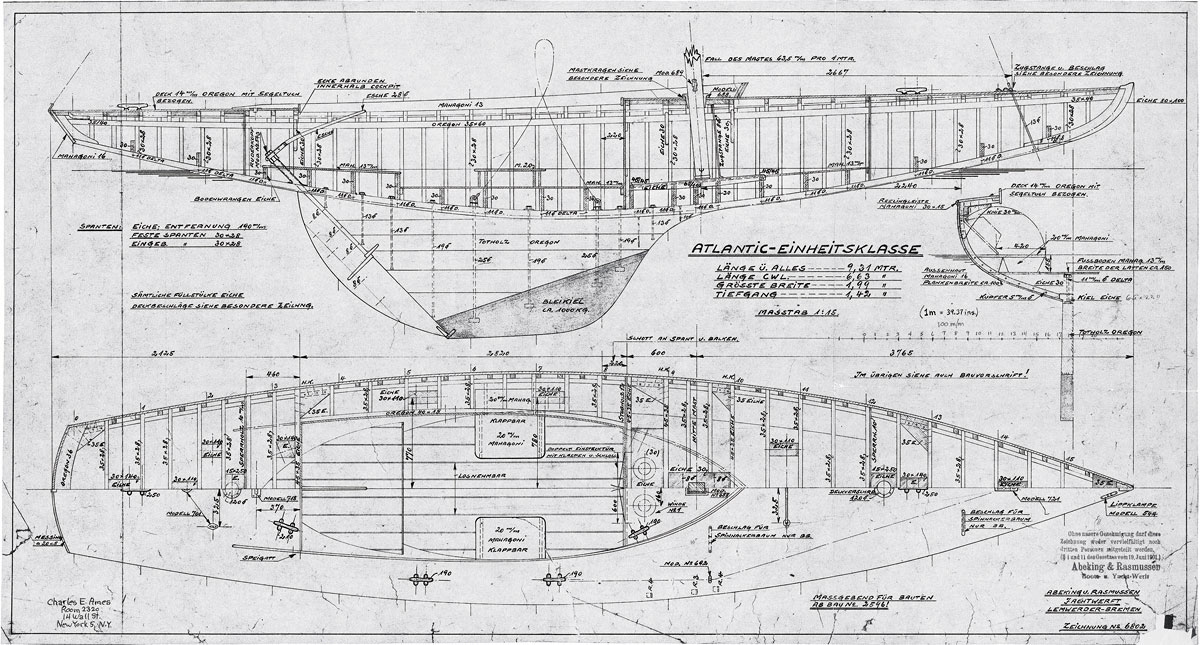

Atlantic Class Archives

With her moderate displacement, U-shaped sections, large sail plan, and light construction, the “Atlantic-Boote” (shown here in the Abeking & Rasmussen construction plan) was not another deep-hulled heavyweight inspired by the meter-boat classes. The seats for the crew were optional.

With the complicated meter-boat projects behind him in early in 1928, Burgess drew up the plans for a new one-design class, which he and Rasmussen called the Atlantic Coast One-Design. The boat measured 30′ overall and 21′ on the waterline, and was intended as a daysailer-racer. Despite competition from several existing classes of that size, its popularity was explosive: There were so many Atlantics on western Long Island Sound in 1929 that the race committee for the area’s big regatta, Larchmont Race Week, divided them into two fleets of 30 boats apiece. To put this into perspective, another popular class, the Sound Interclub (see WB No. 242), had been considered a success with 27 hulls. Within two years, Atlantics would account for 99 of the 150 boats Burgess and Rasmussen designed and built together.

Freed of the International Rule that shaped the heavy meter-boats, Burgess called on his nearly lifelong experience with fast, extreme craft in the design of the Atlantic. One of these influences was the Sonder Boat, a radical, restricted class of long-overhang, lightish-displacement keelboats that had been popular before World War I. The prototype of what Rasmussen called the Atlantic-Boote arrived in New York in the summer of 1928 was not as extreme as the Sonder Boat, yet its 4,559-lb displacement was two-thirds the weight of other 30-footers of her day. Here was a boat that promised to perform well. Her sail area/displacement ratio (SA/D) of 23.3 was well above the Sound Interclub’s 20.6, the Herreshoff S-boat’s 19.6, and the 18.4 of the soon-to-arrive International One-Design (popularly known as the IOD and a close cousin to a 6-Meter; see WB No. 250,page 40 for an account of its development). The more modern Shields class is in the heavy meter-boat tradition, with its 20.8 SA/D ratio.

As Burgess spent a good part of the 1928 summer taking the prototype from yacht club to yacht club, the sailors’ response was very strong. Rasmussen stepped up the specifications for the production boat, replacing the iron ballast with lead and the cedar planking with mahogany. Planks were fitted tight, without caulking, over oak frames on 8″ centers; they were fastened with silicon-bronze screws. Thanks to the depressed German mark and A&R’s assembly-line techniques, the price was low at $1,800 (about $25,000 today). That was about half the price of a similar-sized Herreshoff-built S-boat.

Rosenfeld Collection, Mystic Seaport

The original boat featured a straight-leech, high-boom mainsail, self-tacking jib, single-luff “balloon” spinnaker, and simple rigging (except aloft to support the big rig).

Everybody lauded the Atlantic’s performance. “Those who take pleasure in sailing a boat which is light and delicate on the helm, and lively to handle, should appreciate this craft,” wrote a Yachting magazine correspondent who sailed the prototype. Lorna Whittelsey Hibberd, in her oral history, described racing an Atlantic in an inter-class team race against the top Sound Interclubs: “A lot of the Interclubs got upwind first, including Arthur Knapp. But then when we got on the reach, we just went down the waves and surfed. The Atlantic was much faster. They were a good fun boat.” Fun to sail and fast, the “good fun boat” had a striking appearance, too, with a snub bow, a low profile unobstructed by a cabin, and a long afterdeck leading back to a graceful counter stern. When a class champion of the 1960s, Joe Olson of Cedar Point Yacht Club in Westport, Connecticut, called Atlantics “our gallant beauties,” he expressed the devotion of many sailors. A more recent Atlantic owner, Dick Morris, who sails at Niantic Bay Yacht Club, in Niantic, Connecticut, has described his decision to buy into the class in these words: “I joined the cult and bought an Atlantic.”

As much as the cultists have loved the Atlantic’s looks, what won their hearts for keeps was its performance—and not just downwind. Karl Kirkman, a naval architect who has raced an Atlantic successfully against other keel boats, has explained the boat’s all-round ability: “To a naval architect, the most amazing thing I found was the way Burgess used powerful, almost scow-like ends to the hull to gain sailing length. The boat sort of goes the same speed upwind and down in moderate conditions because of the ability to increase the sailing length when heeled. Since my Atlantic races amongst a Shields fleet, it is easy and instructive to watch them together near the start, and see the wizardry of Burgess before the Atlantic inexorably pulls away.”

Jimmy Rasmussen was so pleased by the boat’s immediate success that he became eager to place boats on the Pacific coast. When he changed the name from Atlantic Coast One-Design to Atlantic Class, some wags, inspired by the country’s largest national grocery chain, nicknamed the boat the Atlantic & Pacific class. “How those A&P boats could run and reach!” Yachting editor Sam Wetherill exclaimed. The Atlantic’s West Coast initiatives were unsuccessful until the Kutscher family moved from Connecticut to Vashon Island, Washington, bringing with them Atlantic No. 62 for daysailing on Puget Sound.

Two years of deliveries during 1929 and 1930 created 13 Atlantic fleets that ranged from the south shore of Long Island, at Cedarhurst, New York, to Long Island Sound (10 fleets), on to Warwick, Rhode Island, in upper Narragansett Bay, and, finally, as far east as Portland, Maine. A very few boats had small cuddies, but most had wide-open cockpits that became quite damp in even a short chop. The Cedarhurst sailors eventually tired of the long tow out through shallow Great South Bay to the racecourse on the ocean, the Warwick fleet was wiped out by the hurricane of 1938, and the Portland boats migrated to Kollegewidgwok Yacht Club in Blue Hill, Maine. Today there are five fleets. In order of seniority, they are Cold Spring Harbor, New York; Niantic Bay (Connecticut) Yacht Club; Cedar Point Yacht Club, Westport, Connecticut; Madison (Connecticut) Beach Club; and Kollegewidgwok Yacht Club.

Rosenfeld Collection, Mystic Seaport

Atlantics in the large Western Long Island Sound fleet approach a mark near Execution Rock, around 1950. By then the boat’s devotees were worrying enough about structural problems to bar Dacron sails, limit boom vangs, and think about replacement hulls.

Fleet No. 1, the founder of the class association and the author of the class rules, was the Pequot Yacht Club at Southport, Connecticut. The effort was led by Fred T. Bedford, a small-boat enthusiast who had started out in extreme one-off catboats in the 1890s but quickly tired of the yachting arms race. “Nobody minds being beaten in competition where conditions are equal for the competitors,” he observed in Edwin J. Schoettle’s book about American yachting in the early 20th century, Sailing Craft, “but who will voluntarily enter a race in which he is licked before he spreads a sail?” Bedford leapt into the first one-design classes. When the prototype Atlantic turned up at Southport and beat his Star boat, he made the switch and 19 of his friends quickly followed.

The first rule book seems innocent in its simplicity, with 11 plainly worded regulations taking up just three pages. Rigging was tightly controlled, in-season haulouts were restricted, and purchase of new sails was limited. Those original sails look odd to us today: the straight-leeched mainsail, the high-clewed self-tacking jib, and the tiny “balloon” spinnaker with its sheet running upwind of the headstay. When more modern sails were allowed, as with all class rules they had to be approved by the owners. The Atlantic’s well-organized class association, tight rules, and large numbers led to its frequent selection in the 1930s as the boat for national and regional women’s, junior, intercollegiate, and interscholastic championships. The interscholastic Clifford D. Mallory Trophy features a tiny model of an Atlantic.

In 1929, the class held its first championship regatta, at Pequot, in a three-race series won by James Tillinghast, from Warwick. Soon the owners included J-class AMERICA’s Cup figures such as George Nichols and Clinton Crane. The celebrated “gray fox of Long Island Sound,” Cornelius Shields, sailed Atlantics for a while. In his autobiography, he said that one of the two most important sailing prizes he ever won was the 1931 Atlantic Class Championship. (Yet he preferred heavy displacement and founded two classes from the meter-boat school, the International One-Design and the Shields.) Other Atlantic sailors were the three winning skippers of the first four AMERICA’s Cup contests of the 12-Meter era, from 1958 through 1967: Briggs Cunningham, Emil “Bus” Mosbacher, Jr., and Robert N. Bavier, Jr. Mosbacher’s first mate, Victor Romagna, and AMERICA’s Cup tactician Tom Whidden were also weaned in Atlantics. All five of these sailors have been elected to the AMERICA’s Cup Hall of Fame. Amid all that young, famous talent, the first two-time class champion (in 1937 and 1938) was a disabled sailor named Mills Husted. With his left arm withered by a birth defect, he steered his well-maintained RUMOUR (Atlantic No. 27) from the port side regardless of which tack he was on.

There is continuity in Atlantic fleets. Families are interwoven with the boat’s history. I know this from my own experience at the Cold Spring Harbor Beach Club, on Long Island. Founded in a former vacation hotel as a family summer center in 1921, the club acquired an Atlantic fleet in 1930. Competition was serious. “It was always intense around the house on Saturdays,” Louise Earle Loomis, the daughter of one of the pioneer Beach Club skippers, has told me. But competition had personal connections. In the 1930s, Atlantic No. 94, LYNX, was sailed by the young man who would become my father, with a regular crew that included his own very game father, whose chief sporting interest was golf. Among his competitors were Dad’s schoolmates, named Page, Lindsay, and Noyes. Decades later, my father was back racing Atlantics at Cold Spring Harbor against (and sometimes with) those former classmates. At the Atlantic Class Championship at Cold Spring Harbor last September, I trimmed the mainsheet for George Lindsay, the son of one of my father’s opponents of 50 to 80 years ago.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

The gamble on the Burgess design in the 1920s paid off, and so did the later bets in the 1950s on new construction. Here, the mostly fiberglass Atlantic fleet contests the national championship on Blue Hill Bay, Maine, in 2008.

Women were always sailing Atlantics. One Cold Spring Harbor boat for decades was the bright-red ZEST (Atlantic No. 95), sailed by Anna Matheson Wood, known to all as “Aunt Nan.” She was a leader in the national movement to establish women’s sailing as a sport. At Blue Hill, a popular summer haven for New Yorkers, many of the Atlantics in the Kollegewidgwok Yacht Club fleet were sailed by women in July when the men were back at work in the city. Some boats were also sailed by the same women in August, after their husbands came Down East. One of the sailing seasons of the longtime fleet leader, Alida Milliken Camp, was described as follows by Kollegewidgwok historian Berto Nevin: “They won every race, nearly sinking in one when a squall knocked them down, but Alida was a determined skipper and no squall was going to deny her, so she sailed on, her crew bailed as they raced to another victory, finishing with the perfect score.”

At Pequot Yacht Club, “Miss Charlotte Perry” (as the newspaper reporters called her)—better known as Sharlie Perry Barringer—sailed in Atlantic No. 6, CAROLINA, from age 14 on. Her victories were not always fully celebrated. After she won a race by six minutes, a reporter felt called upon to comment, “A girl from the Pequot Yacht Club gave proof to the old adage about the lethal qualities of the female of the species, if proof were needed, by walloping her male rivals in the biggest group of the day, that for Atlantic Class boats.” In 1944 she won the Class Championship with a 1–1–10–5–2 record. Later, with her husband, Rufus Barringer, Sharlie raced CAROLINA at Cold Spring Harbor. “I would love to sail in an Atlantic again,” she said recently. “I still think the Atlantic is one of the most beautiful boats ever. We used to go cruising in the Atlantics…. We had so much fun in those boats. When I look at them today, I think, ‘How in the world did they put us in these boats at such a young age?’”

Marking the class’s 20th birthday in 1949, the knowledgeable yachting writer Everett B. Morris identified three reasons for the Atlantic’s success: (1) “the vigor with which its converts sing its praises,” (2) “the solid all-round performance of the boat modernized with loose-footed jib and parachute spinnaker,” and (3) “the impossibility of getting anything anywhere near as good for the same price.” That bargain price was not necessarily a good thing. The Atlantic was inexpensive because it was lightly built, fragile, and aging quickly. The boom vang (then called the “boom guy”) was permitted by the rules to have only two parts because anything stronger might break the boom, and maybe weaken the lightly built hull. Most sailors preferred the expedient of the “human boom vang”—a sailor seated on the boom as far aft as he or she dared. After the first synthetic sail fabric, nylon, was allowed in the 1940s, the sails proved so stretchy that sailors demanded that they be free to experiment with low-stretch synthetics, such as Orlon and the rumored “miracle fabric” (which eventually appeared as Dacron). But class chairman Charles Ames, a Cold Spring Harbor sailor, feared that Dacron might overstress the hulls, so the Rules Committee barred it.

The fact is, Atlantics had been leakers right from the start. After the first shipments from Germany in 1929, the Burgess and Abeking & Rasmussen offices, recognizing that the frames were too small and flexible, scrambled to design bigger ones for the 1930 boats. This improvement, however, did not cure the inherent flexibility in these lightly built, flattish-bottomed, hard-driven boats. “Theoretically, the Atlantics are planked with mahogany on oak ribs,” Everett Morris observed in the 1940s, “but the more active these boats become, the stronger grows the belief that they are constructed of rubber.” Norman B. Peck, Jr. of Niantic Bay, the class’s 16-time national champion, has used another analogy: an Atlantic he sailed in the 1940s, he told me, was “a wicker basket.”

Rosenfeld Collection, Mystic Seaport

Briggs Cunningham, shown here in his still-wooden A12, SPINDRIFT, in 1954, played a major role in the process that introduced fiberglass construction to the Atlantics.

If the boats were inexpensive to buy, they were extremely expensive to maintain. Charles Ames estimated his total maintenance expense over a few years in the late 1940s and early 1950s at $3,903 ($38,000 in 2015 dollars)—this for a boat that he had purchased for $2,000. Boatyards on Long Island Sound had a set of special molds for replacing or sistering broken Atlantic frames—and they did a lot of business. Ames and the other sailors loved their Atlantics very much and were prepared to do anything to keep them sailing. Discussions with boatyards about building new planked hulls (Abeking & Rasmussen, then enjoying a second boom producing Concordia yawls and sloops for the U.S. market) or hot-molded hulls (Luders Marine Construction Co.) went nowhere.

Then a third option surfaced: a new building method (soon to be called fiberglass) using layers of synthetic fabric and polyester resin. A letter to four of the very few boatbuilders who worked with the material turned up just one show of interest, Lester Goodwin of Cape Cod Shipbuilding in Wareham, Massachusetts. “We are sure that we can equal or reduce the weight on the Atlantic and have a boat much stronger than your present wood boat,” Goodwin wrote the Rules Committee. After a long career as a salesman for the famous powerboat racer and boatbuilder Gar Wood and other yards, Goodwin had bought Cape Cod Shipbuilding and acquired the rights to build boats to several Herreshoff designs. “To visit the yard was a flashback to the past,” Cedar Point Atlantic sailor Jim Bradley has told me. “Mr. Goodwin often had a fire going in his office fireplace that he fed with teak and mahogany scrap from the yard. He was an avid hunter, so when he sat down he had to kick his hunting dogs off the chair. When he took you to lunch, it was to a local diner where, no matter what you wanted, you got a cheeseburger because that’s what he ate.”

Goodwin’s proposal to convert wooden hulls to fiberglass put the Atlantic Class on the spot. A quarter century after Burgess took a gamble when he made the Atlantic so different from other boats its size, the class in the early 1950s was challenged to make another big bet: To save their Atlantics from sinking, they would need to use a radical new building material that might produce boats much faster than the old woodies. Desperate to save the boat they loved, the class went ahead with the conversion plan.

Goodwin took the next step in what he dramatically referred to as the “reincarnation” of the Atlantic by selecting RUMOUR, Mills Husted’s old boat, as the plug from which to produce the mold for the first fiberglass hull. Briggs Cunningham financed the process with a loan. An heir to a Midwestern fortune and Fred Bedford’s son-in-law, Cunningham was an automobile racer, had won three Atlantic championships, and would win the AMERICA’s Cup in 1958 as helmsman of the 12-meter COLUMBIA. None of this went to the head of this modest man who, among his many contributions, donated the schooner BRILLIANT to Mystic Seaport.

When RUMOUR’s fiberglass hull was found to be 300 lbs lighter than the old one, compensating lead ingots were placed in the bilge before the boat was towed to Southport for the 1954 Class Championship, where her skipper would be Cunningham. A member of that delivery crew, Goodwin’s son Gordon, has told me, “As we pulled into the dock, Briggs stepped on board, inspected the rig, and said, ‘This rigging is too tight for an Atlantic.’” Once under sail, he quickly discovered that the fiberglass hull could carry a tauter rig than a soft wooden boat. To the relief of all, the first ’glass boat finished fourth of 28 boats: She was competitive but not dominant.

Benjamin Mendlowitz

One of the few wooden Atlantics still sailing after the 1960s, TRIPLE THREAT shows off the Burgess lines and original rig after her 1994 restoration by Frank Day, Jr. This was her final sail before going to Mystic Seaport to join its permanent collection of historic watercraft.

The Cape Cod yard sold RUMOUR to John Hersey, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Hiroshima and other books. After a summer of racing at Pequot, Hersey was asked by Charles Ames if he felt 100 percent favorable about the boat. Hersey replied, “My answer has to be that I feel 1,000 percent…. We never bail. The crew is happy. In heavy weather, where once the dried-out topsides took in water in a way familiar to all Atlantic sailors, we now can sit and chat and look at the view—we can concentrate on racing, too.” He added, “I’ll say that I feel sure that while the ’glass boats will not outclass the others, they will sail with the best of the wooden boats, other things being equal.” Twenty hulls were converted in 1956–58, and many more later made the switch at Cape Cod Shipbuilding or, for a few years, at the Seafarer yard on Long Island. Meanwhile, new boats with sail numbers over 99 were also built. In time, the ’glass boats, with their compensating lead in the bilge, did prove faster in most conditions, as well as more dry and less costly to maintain. Sharlie and Rufus Barringer, owners of CAROLINA, held out for wood. “That was a decision that was both philosophical and economical,” she said. “We just didn’t go that route. Most of the time, we were competitive. But when it blew hard or if there was a sea, the fiberglass boats seemed to sail through the waves better.” Some owners were distressed as they gave up their dear old woodies. “Cutting up A30 was very sad,” Jim Bradley said of the conversion of his INGÉNUE. “The boat was unbelievably sound. The Germans built an extremely good boat.” A compensation was that the new boats looked quite good. “Unlike other fiberglass conversions, it didn’t change the boat’s character,” says Atlantic sailor and photographer Guy Gurney. “It looks like a wooden boat that happens to have a fiberglass skin.”

Today, Atlantic sail numbers are at 149, and two-thirds of the 87 existing Atlantics are sailing and racing under powerful modern rigs and aluminum spars. A recent National Championship at Blue Hill had 41 entries, a majority of them trailered hundreds of miles from their home clubs. The quality of competition at the top of the fleet is very high. I can’t recall sailing in a boat pushed so aggressively, and so intelligently, as Norm Peck’s MISS APRIL (Atlantic No. 130) was in a Sunday afternoon race at Niantic Bay in 2013.

About 14 wooden Atlantics are believed by the class to have survived. One of the best known of them is No. 23, TRIPLE THREAT, which after a long, active life, is in storage at Mystic Seaport. Two other woodies are known to be sailing still. The Barringers’ CAROLINA, somewhat modified from the Burgess-Abeking specifications and now called SILVERFISH, is owned and sailed by boatbuilder Steve White in Maine. The other is PISCES (No. 69), owned by Harry Fish, Jr. of Jonesport, Maine.

Fish’s father acquired PISCES for $1,000 from a Blue Hill owner in 1972, and she was first to finish in that year’s big race, the Bucks Harbor Regatta. A retired high school math and science teacher, Harry Jr. continues to sail the boat under the burgee of the Port & Starboard Yacht Club. “She’s all original,” he told me in 2013, with her old wooden mast, high-cut jib, and the original bronze fittings. The big event is an annual race at Jonesport with a three-mile windward leg. PISCES is up to it, and so is Fish, another member of the cult. “It’s such a spectacular boat! It looks like it’s going about 100 mph just lying at the mooring. Then when you sail her she’s a black line in the water with sails sticking out of her. Everybody who sees the boat loves it. I’ve sailed a lot of other boats, but I’ve been fascinated with this one since the day I first sailed her.

“The Atlantic is such a dream to sail. It’s almost like it knows where to go on its own. We finish first always. My racing strategy is go fast all the time, and faster when we can.”

John Rousmaniere, a regular contributor, is author of the book The Great Atlantic: The First 85 Years (Smith-Kerr, 2014).