TEAL

Sentinel of the Alaska coast

Sentinel of the Alaska coast

BRUCE HALABISKY

The 78′-long TEAL of 1927 motors through San Juan Channel just off the entrance to her home port of Friday Harbor, Washington.

BRUCE HALABISKY

Kit Pingree, TEAL’s owner and captain, bought the former fisheries patrol boat in 2008.

When I first met with Kit Pingree, she was midway through a three-week haulout of her 78′ motor vessel, TEAL. Between forecasts of rain showers, the first warmish days of the northwest spring had made an appearance, lending urgency to the varnishing and painting schedules and a long list of other tasks. Kit was on deck preparing TEAL’s mizzen boom for a new steadying sail, which the boat hadn’t had since its last days of government employment in the 1960s.

“We’re getting ready to go back to Alaska,” Kit said with a smile, referring to her one-man crew and fiancée, Doug Tones, who could be heard somewhere on the ground attacking the rust on TEAL’s 500-lb anchor with a needle gun. Adding to the yard’s bustle and noise, shipwrights in Port Townsend spiled new Douglas-fir planks nearly 3″ thick and muscled them into position over massive 10″-wide frames.

“There are six or seven bad planks that came from [the forests around] Mount St. Helens after she erupted in 1980,” Kit said. “Apparently, the trees got so hot that all the oils boiled out of the wood.”

Inside of TEAL’s large saloon, Kit showed me another small but significant project on the “to do” list: carving a pair of salmon. Old black-and-white photos of TEAL from the late 1920s show a pair of what appear to be 2′-long bronze salmon mounted port and starboard on TEAL’s bow. These fish were the mark of the United States Bureau of Fisheries patrol boats, among which TEAL was considered the “Queen of the Fleet.” Although no longer a government workboat, TEAL’s bronze salmon and her upcoming voyage represent two consistent themes in her nearly 90-year history: fish and the Alaskan coast.

Patrolling “the Territory”

Back in the 1920s, Alaska was a vast, roadless territory—statehood was still decades away. Anchorage, at the head of Cook Inlet, had a population of fewer than 2,000, and air service was minimal; most travel to and along the Alaskan coast was by boat. The Alaskan fishing fleet and the government agencies overseeing it were based largely out of Seattle, 1,500 miles away. In 1927, to better serve this extensive coastline, the government commissioned TEAL, a 140-ton motor vessel specifically designed for the job of monitoring and protecting the Alaskan fish stocks.

PUGET SOUND MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY/JOE WILLIAMSON COLLECTION (2078)

Launched in 1927 at Kruse & Banks Shipbuilding in North Bend, Oregon, TEAL was commissioned to patrol the rich Alaska fisheries starting in 1928 for the federal Bureau of Fisheries, later the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. She wintered on Lake Union in Seattle, Washington, and made annual voyages to the north. She was first loaned, in 1955, then sold, in 1959, to the State of Alaska and continued in fisheries patrol service until the mid-1960s.

TEAL’s design came from Seattle-based naval architects Leigh Hill Coolidge (1870–1959) and Harold Cornelius Hanson (1892–1975), who were design partners for a year and a half starting in 1927. The boat was to be 78′ on deck with a breadth of 18′ 6″ and a draft of 8′ 7″. Both designers were experienced in drawing commercial vessels and yachts. Hanson, in particular, became known for his contributions to the Northwest “trawler-yacht” style of motorboat. In the early 1920s, he worked for the Seattle yacht designer Ted Geary, which may explain TEAL’s elegant, yacht-like features—especially her fantail stern and graceful sheer. Coolidge was a native of Portland, Maine, who worked as a shipwright in Boston, Massachusetts, before heading to Puget Sound. He worked on the designs of schooners built in Ballard, and his yacht commissions included the Blanchard 36′ Standardized Cruiser, 24 of which were built between 1924 and 1930 as stock cruisers.

The contract to build TEAL went to Kruse & Banks Shipbuilding of North Bend, Oregon, on Coos Bay. Kruse & Banks was noted for building some of the last large West Coast schooners after World War I and later for building minesweepers during World War II in what historian Steve Priske has called one of the most productive shipbuilding regions in the United States.

Although launched in 1927, TEAL didn’t go north to Alaska until the following year, when she sailed in tandem with another Hanson-designed vessel, the 92′ CRANE built in Port Blakely on Bainbridge Island, near Seattle. PELICAN, a sistership to TEAL, was built in Newport News, Virginia, in 1928; she initially served the East Coast fisheries but in 1941 was transported on a U.S. Navy ship to the West Coast to serve alongside CRANE and TEAL. All three of these Hanson-designed motorboats are still operating today—TEAL and PELICAN as private yachts and CRANE as a fish packer in Alaska.

BRUCE HALABISKY

During her conversion for pleasure, TEAL’s wheelhouse and main deckhouse retained their original outboard profiles, but interior modifications allowed two doors on each side of the deckhouse to be closed off.

“Named for the wildfowl and big game animals they protect throughout the mighty northern empire of Alaska,” remarked Frank W. Hynes, a Fish & Wildlife Service director in the 1940s, “these sturdy little vessels carry on a colorful and vitally important battle against the forces of both man and nature to prevent the depletion of fish and game resources. They are strongly built and seaworthy, embodying the best lines of halibut schooner and purse seiner.”

TEAL’s principal mission was to patrol Alaska’s Cook Inlet, but her responsibilities during 40 years of government service were broad and varied. Until the 1950s, she spent her winters at the Bureau of Fisheries base on Lake Union in the Fremont district of Seattle, during which time repairs and maintenance would be carried out. In early spring, TEAL would head north again, often in the company of CRANE and PELICAN or one of the agency’s other vessels, carrying supplies for Alaska’s remote communities and also government officials and fish biologists. Her duties in Alaska involved tagging herring, inspecting salmon spawning grounds, checking fishing licenses, and, in 1938, extensively surveying Prince William Sound streams. TEAL’s logbooks show that in some years she covered more than 11,000 miles, implying multiple trips from Seattle to Alaska.

During World War II, TEAL and the other vessels of the Fish & Wildlife Service (which incorporated the BOF in 1940) were armed to patrol Alaska’s coast against Japanese invasion. In 1962, to confront an invasion of another kind, Alaska Governor William Egan ordered TEAL to seize the Japanese fishing vessel OHTORI MARU, which was illegally taking halibut from Alaskan waters.

PUGET SOUND MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The engineroom for the massive Washington-Estep 180-hp diesel engine, which was replaced in the 1990s, occupied roughly a third of TEAL’s belowdecks space.

PUGET SOUND MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

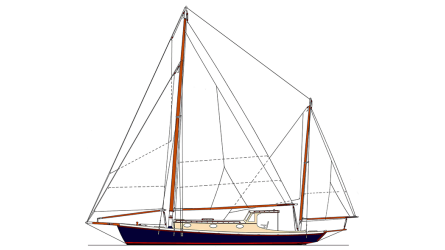

TEAL was designed by L.H. Coolidge and H.C. Hanson, two of the Northwest’s most prominent naval architects of the early 20th century, during the mere year and a half that they were partners. Their lines plans show an elegant and seaworthy hull specifically designed to cruise the capricious Alaska coast. TEAL and other Alaska fisheries patrol boats inspired one Fish & Wildlife Service director to write that such boats “embody the best lines of the halibut schooner and purse seiner.”

PUGET SOUND MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY

TEAL was built in North Bend, Oregon, a shipbuilding center where prized boatbuilding woods such as Douglas-fir, Sitka spruce, and Port Orford cedar were plentiful at the time of her construction. Her scantlings called for double-sawn frames on 20″ centers, with paired 8″-thick futtocks in way of the engineroom and 5″-thick futtocks elsewhere. Her hull planking is 2⅝″ thick, with 3¼″-thick garboards. On the interior, her structure was powerfully reinforced with bilge stringers composed of seven 7½″-wide strakes 3¾″ thick.

COURTESY OF KIT PINGREE

TEAL had a varied working career after being sold by the Alaska government in the mid-1960s. In 1997, she was bought for pleasure use and taken to Port Townsend, Washington, for a haulout and an extensive restoration.

George Shaw of Kenai, Alaska, who served as TEAL’s engineer from 1953 to 1955 and is now 87 years old, fondly remembers his summers aboard TEAL when he was in his 20s. “We were a four-man crew: skipper, cook, engineer, and seaman. It was the best of all the boat jobs I had.” Shaw was an engineer on ten or eleven vessels between 1944 and 1960, and on TEAL he managed the 180-hp six-cylinder Washington-Estep diesel. “To go from forward to reverse, the engine had to be shut down, a cam-shaft shifted, and then the engine restarted in reverse using a blast of compressed air. It didn’t take more than a couple of minutes….” He specifically remembers installing TEAL’s 54″-diameter, five-bladed propeller in 1954, the same propeller the boat carries today.

“TEAL was built for the Cook Inlet area and thus had large freshwater tanks due to the difficulty of getting water in the inlet,” Shaw said. The tank capacity was 2,000 gallons.

In 1957, the federal government loaned TEAL to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and after Alaskan statehood in 1959 her ownership was transferred permanently. In the mid-1960s, TEAL was sold into private hands, which precipitated her decline and nearly her demise.

Decline and Resurrection

BRUCE HALABISKY (ALL)

ABOVE LEFT—Since buying the boat in 2008, Kit Pingree has continued TEAL’s maintenance and restoration. In 2016, the boat was hauled again at Port Townsend for additional work, mainly painting. Here, her 500-lb anchor is visible. ABOVE CENTER—In the latest haulout, a handful of planks needed replacement, exposing TEAL’s heavy double-sawn frames. ABOVE RIGHT—In 2000, a 350-hp Cummins 855 diesel replaced TEAL’s enormous Washington-Estep engine, saving 10,000 lbs of weight that was offset by additional ballast. Repowering opened space for accommodations but still left an ample engineroom.

After the state sold TEAL, she worked for a few years as a tug in southeast Alaska and then as a commercial fishing vessel. A May 1970 photograph from a Juneau newspaper shows TEAL aground on a rock, a telling image of her treatment during the next several decades. Victor Lundquist, a historian for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, wrote an account of TEAL’s first 31 years of private ownership, listing a litany of owners and a steadily declining value. A 1982 classified advertisement from The Seattle Times reads, “M.V. TEAL—Just repossessed and to be sold as-is. Cabin rough, hull condition unknown. Min. Bid $12,500.”

BRUCE HALABISKY

A belowdecks owner’s stateroom provides ample and comfortable accommodations, using space formerly occupied by officer’s quarters and part of the engineroom. She also has a double-bed guest stateroom, a “bunk room” with three single bunks and one double berth, and in fair weather a double berth can be made up “under the stars” on the afterdeck.

In 1997, after being out of the water for 15 years, TEAL was brought back from the brink of perdition when she was purchased by Rod and Gayle Jones. The couple, with the help of Port Townsend shipwrights, undertook an extensive rebuild that took 25 months and cost an estimated $750,000. “When the Joneses acquired TEAL,” Lundquist wrote, “she was on blocks, badly deteriorated and nearly beyond saving.”

The restoration used 16,000 board feet of clear old-growth Douglas-fir and cedar and included the replacement of 248 planks. “Everything from the waterline up is brand-new on the hull,” project foreman Paul Nelson told a Peninsula Daily News reporter on the day of her relaunching, July 13, 1999.

With the hull rebuilt, TEAL was floating again, but the Joneses continued the restoration on the water, followed by two subsequent owners. In 2000, a 350-hp Cummins 855 engine replaced the original Washington-Estep diesel. The 10,000 lbs of weight saved was replaced by concrete ballast, thus freeing up much of the engineroom for conversion to living and working space.

In 2004, TEAL was sold to Denny Mahoney of Anacortes, Washington, who finished the interior and made modifications to accommodate his son’s wheelchair. Mahoney also added a bow thruster and hydraulic steering. In 2008, Mahoney put TEAL up for sale. At a festival in Anacortes, he struck a deal with Kit Pingree, who offered 5 acres of land on San Juan Island in exchange for TEAL.

BRUCE HALABISKY (ALL)

ABOVE TOP—TEAL’s expansive main saloon was created during an earlier restoration by removing interior bulkheads that formerly divided the space into numerous small cabins to house marine biologists, game wardens, crew, and any number of eclectic passengers. Looking forward, the steps to starboard of the bulkhead lead up to the wheelhouse. The railing guards other steps leading down to the owner’s stateroom. ABOVE CENTER—The well-appointed galley spans the width of the deckhouse aft and is well lighted by the original 14″ portlights. ABOVE LOWER—In the main saloon (looking aft toward the galley), the living space includes furniture built by Kit Pingree herself, inspired by 1920s styling.

Return to Alaska

Under Kit’s guardianship, the restoration of TEAL has continued. What George Shaw, the engineer, remembers of TEAL’s accommodations was destroyed and then gutted during TEAL’s years of abandonment. Originally, multiple cabins had individual access along the side decks. Now, a spacious saloon spans the breadth of the cabin from the wheelhouse aft to an enlarged galley. Kit, who is 68 years old and was married for 25 years to a finish carpenter from whom she picked up woodworking skills, designed and built some of the interior furniture in the style of the 1920s. She installed a heating system and a hydraulic crane. TEAL originally was rigged with a steadying sail, a rig Kit is restoring in conjunction with Port Townsend sailmaker Carol Hasse.

Kit, who grew up on and around wooden boats in San Francisco, moved to the San Juan Islands specifically with the idea of getting back into boating. “My father was an avid sailor and navigator,” Kit said. While she was growing up, her family cruised on the Academe yawl GOLDEN BIRD, and the Mayflower ketch COURTSHIP.

For 10 years after moving to San Juan Island, she used her property for wedding receptions and vacation rentals. “It consumed all my summers,” she said. Then came the opportunity to trade 5 acres of that land for TEAL.

“She has a way with people falling in love with her and emptying their pockets,” Kit said, joking about the financial commitment necessary to keep TEAL running. “We haul out every three years and do a lot of the work ourselves.” Doug’s experience as an engineer at The Boeing Company has been put to use simplifying systems and troubleshooting problems. To save money, Kit buys fuel in bulk, taking advantage of a price break for purchasing more than 750 gallons. At a cruising speed of 8 knots, TEAL uses 2 gallons of diesel per hour, and she has a fuel capacity of 2,000 gallons.

Last year, Kit and Doug—both of whom have 100-ton master’s licenses—took TEAL to Alaska and back,“3,224 miles,” Doug said, after doing a bit of math, “...according to the logbook.” That was Kit’s second trip north in TEAL, and shortly she and Doug will leave on another run up to Alaska, retracing a route the vessel has covered dozens of times during the past 90 years. “People come up all the time and say, ‘I remember this boat,’” Kit said.

Sometimes Kit and Doug cruise with friends aboard, but often it is just the two of them running the vessel. And Kit doesn’t hesitate to take TEAL out on her own. “The first time I docked her by myself I had nightmares the night before. The previous owner, Denny, told me ‘It’s okay, she gets smaller,’” Kit said. “Now I can back her into a slip, and it’s really kind of fun.”

Recently, when backing out of the Travelift after the haulout in Port Townsend, “the bow thruster started up but then it died,” Kit said. Doug ran below to troubleshoot. (The problem, discovered later, was an airlock from a recent filter change.) “It was blowing about 20 knots and I was committed (to making the turn),” Kit said. “Of course, everybody’s watching from shore and yelling, ‘Her bow thruster’s gone.’” Kit kept her cool and patiently worked TEAL around to make the turn.

“The neat thing about TEAL is that she is so heavy you can put her in gear and ‘pop’ her, and she won’t move forward but her stern will kick over—nothing happens fast,” Kit says. “One thing I’ve learned is that I never run her hot, everything is slow and easy.”

BRUCE HALABISKY

Heading east out of Friday Harbor into San Juan Channel, TEAL sails waters that would have been familiar to her previous crews in her many trips north from Seattle to Alaska over the past 89 years. Her red stack is painted with the numerals “1927” to honor the year of her launching.

During my final conversation with Kit, she talked about the beauty of the Alaskan coast and the great fishing she and Doug experienced on their most recent voyage. They showed me a picture of the 97-lb halibut that nearly flipped their dinghy; they talked of the abundance of salmon they caught in secret coves and inlets along the way to last year’s turn-around point at Glacier Bay. This year, they are planning to meet up with George Shaw in Juneau for his 88th birthday. Although no longer used to patrol fishing grounds, TEAL appears to have a secure place on Alaska’s coast with Kit Pingree at the helm.

Bruce Halabisky is a wooden boat builder and frequent contributor to WoodenBoat. In 2015, he received the Ed Monk Memorial Scholarship from The Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle, Washington.