STING RAY V

Ray Hunt’s legendary deep-V cruiser

Ray Hunt’s legendary deep-V cruiser

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

Long a familiar sight in Florida waters, STING RAY V (today renamed STINGRAY) proved to be an able passagemaker on her many voyages between Fort Lauderdale or Boca Grande and New England. Evident here are some of the changes made over time. Originally white, the hull was painted its current color at a later date.

Those with local knowledge will tell you that the New River at Fort Lauderdale, Florida, is a tricky place. There are tight bends, bridges, and of course, currents. There are shallow places and channel markers that can be confusing, especially where the river’s South Fork meets the Intracoastal Waterway. There is plenty of boat traffic, too. Writing about the area some years ago in The Triton, a Fort Lauderdale monthly whose audience is professional yacht skippers and crews, Towboat US Capt. Michael Knecht advised: “It’s a beautiful, scenic waterway but can be quite adventuresome for those who are unfamiliar with it.”

Given the challenges of the river, if you’ve just purchased a boat berthed at the Lauderdale Marine Center, located close by busy Interstate 95 and known as the country’s largest boatyard, it would be prudent to have aboard someone with local knowledge when you first poke the bow of your new boat into the New River’s South Fork. So it was for Holt Massey when he acquired the 50-year-old power yacht STING RAY V in November 2014. He initially retained the services of Capt. Mike Henderson, who had looked after the boat for its previous owner. The goal was to learn to operate and maneuver the 56-footer during explorations of the New River and the many canals that prompted developers in the early 1920s to label Fort Lauderdale “the Venice of America.”

Tied up alongside are large yachts, larger yachts, and towering megayachts, these being so numerous that one can be forgiven for taking their opulence for granted and developing a ho-hum “seen one, seen ’em all” attitude. But as Massey learned with STING RAY V (now named STINGRAY), owners of waterfront homes were quick to recognize that his boat was altogether different, a stunning throwback to another time. “After navigating the bends and bridges and tour boats of the New River,” he said, “we used to practice turning around in our own length in the Fort Lauderdale canals. People would run out of their houses to photograph STING RAY. She really turns heads. She is a piece of history.”

By the early 1960s, when STING RAY V’s story began, her designer, C. Raymond Hunt, was recognized as one of the country’s most gifted racing skippers, and among its most innovative designers. Now that deep-V powerboats are so common, it’s hard to look back and realize just how revolutionary Hunt’s concept was. “Ray was blessed with the ability to create new ideas rather than perfect old ones,” is how Devereux Barker, Hunt’s longtime friend and a onetime Yachting magazine writer, put it.

COURTESY OF C. RAYMOND HUNT ASSOCIATES

This image shows how STING RAY V looked initially. Her transom was unadorned by the later swim platform, door, and decorative carving. A single deck box and tender are mounted longitudinally atop the aft cabin. She flies the private signal of her first owner and the burgee of the New York Yacht Club.

Naval architect John Deknatel, Hunt’s founding partner at Hunt Associates—today C. Raymond Hunt Associates in New Bedford, Massachusetts—remembered how Hunt’s idea for what would become known as the deep-V differed from that of powerboat innovator Lindsay Lord. “[Lord’s] theory was that the hull should have a constant section from ’midships all the way aft,” Deknatel said. “And he advocated a significant degree of deadrise. But he would change the deadrise depending on a specific boat, its application, the hull, and equipment within the hull.

“Raymond’s idea was different. He used the same amount of deadrise from ’midships aft. Intuitively, nobody knows how, he determined the deadrise should be 24 degrees. Today, with all our technology, we know this to be near-ideal. Also, rather than change that angle to meet the demands of different boats, he moved things around within the hull—engines, equipment, and so forth—to make the weight distribution work.” The resulting hulls proved capable of maintaining high speed and directional stability even in rough seas.

In the pioneering years of the late 1950s and early ’60s, there was some skepticism of Hunt’s innovation. Miami’s suntanned, seen-it-all powerboat jockeys who competed regularly in offshore racing didn’t immediately buy the idea. Some laughed at it. The hull was comparatively tippy at rest and Hunt even experimented with water ballast to help stability at low speeds. It also took some time to get the deep-V to turn reliably. But soon enough, people became accustomed to the hull’s dynamics, and steering issues were overcome as rudder development progressed.

Among the most distinctive features of Hunt’s deep-V hulls, including STING RAY V’s, were the dramatically curved strakes applied to the bottom. These strakes had three functions. They helped lift the hull as it gained speed. They added stability, reducing roll thanks to the air trapped between the stringers that cushioned motion in seas. And they helped reduce spray, keeping the boat drier. Needless to say, there were no computer-aided design programs then to assist in testing and refining the strakes. Development was done full-scale in real time, much of it in the waters off Miami during a month of trial-and-error tests in the summer of 1959.

Early on, Hunt’s prototypes caught the attention of Fairey Marine in England. Fairey acquired a license and completed a hot-molded plywood 23-footer in July 1957, the first of 351 Hunt or Hunt-derived deep-Vs that would be built by Fairey and Bruce Campbell Ltd. over the coming years. The big breakthrough in the United States came in 1960 when yachtsman, yacht broker, and powerboat enthusiast Richard Bertram commissioned Hunt to design a 30′ deep-V for the 1960 Miami–Nassau powerboat race. MOPPIE sped over 8′ to 10′ seas without once rolling her propellers out of the water, and she scored a game-changing victory. (See WB No. 245 for the complete MOPPIE story.)

Under the impetus of Bertram, and enhanced by fiberglass production, Hunt’s deep-V sparked a revolution. The Bertram 31 with its “Hydrolift hull” became an instant hit that redefined the market for sport fishermen and cruisers. Hunt, who had patented the deep-V, now welcomed the influx of royalties from Bertram and other builders. (In 1971, Hunt’s patent was invalidated due to several technicalities, one of the greatest disappointments of his professional life.)

Soon, Hunt turned his attention to deep-V power cruisers, the first being his own 47′ YONDER, launched in 1960. YONDER had an aft cabin and an airy, central galley-saloon arrangement suggested by his wife, Barbara. The boat proved to be fast, smooth-riding, and versatile enough to use in a variety of Hunt’s boating experiments.

BILLY BLACK

The aft cabin, labeled “owner’s state room” on the original drawings, features a well-equipped head. The cabin is accessed by four steps leading to the bridge. The layout, with berths port and starboard and a roomy hanging locker, remains as originally designed. The carved stingray on the dresser is one of several aboard.

At some point, probably during 1963, Hunt Associates received a commission to design a yacht larger and more luxurious than YONDER, which was, as Deknatel noted, “rather bare bones with a galley unit out of an RV.” This boat, launched in the summer of 1964, was STING RAY V. Today, in the files of C. Raymond Hunt Associates, STING RAY V is remembered as “the handsomest Hunt custom yacht of her era.”

“We got the commission,” remembered John Deknatel, “from a Stonington [Connecticut] yachtsman and New York Yacht Club member named Bill Brewster who appreciated good boats and upscale automobiles. When he came for meetings, it was usually in a Bentley or a Mercedes-Benz.” (There is nothing to indicate that the boat’s name was influenced by the 1963 Corvette Sting Ray. It is believed that Brewster had named his previous boats STING RAY and that this was simply the fifth one.)

Looking back on the creation of STING RAY V, Deknatel said: “At the time, Spaulding Dunbar was doing some very swoopy powerboats and I was given a shot at creating the outboard profile. We aimed for a sleek look.” With the basics established, Fenwick Williams, Hunt’s longtime designer and draftsman, went to work on the details. “Ray did the hull and Fenwick created the final sheerline and then drew the lines and construction plans as he usually did,” Deknatel remembered.

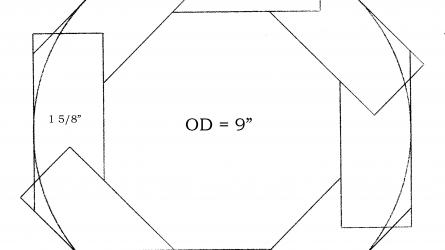

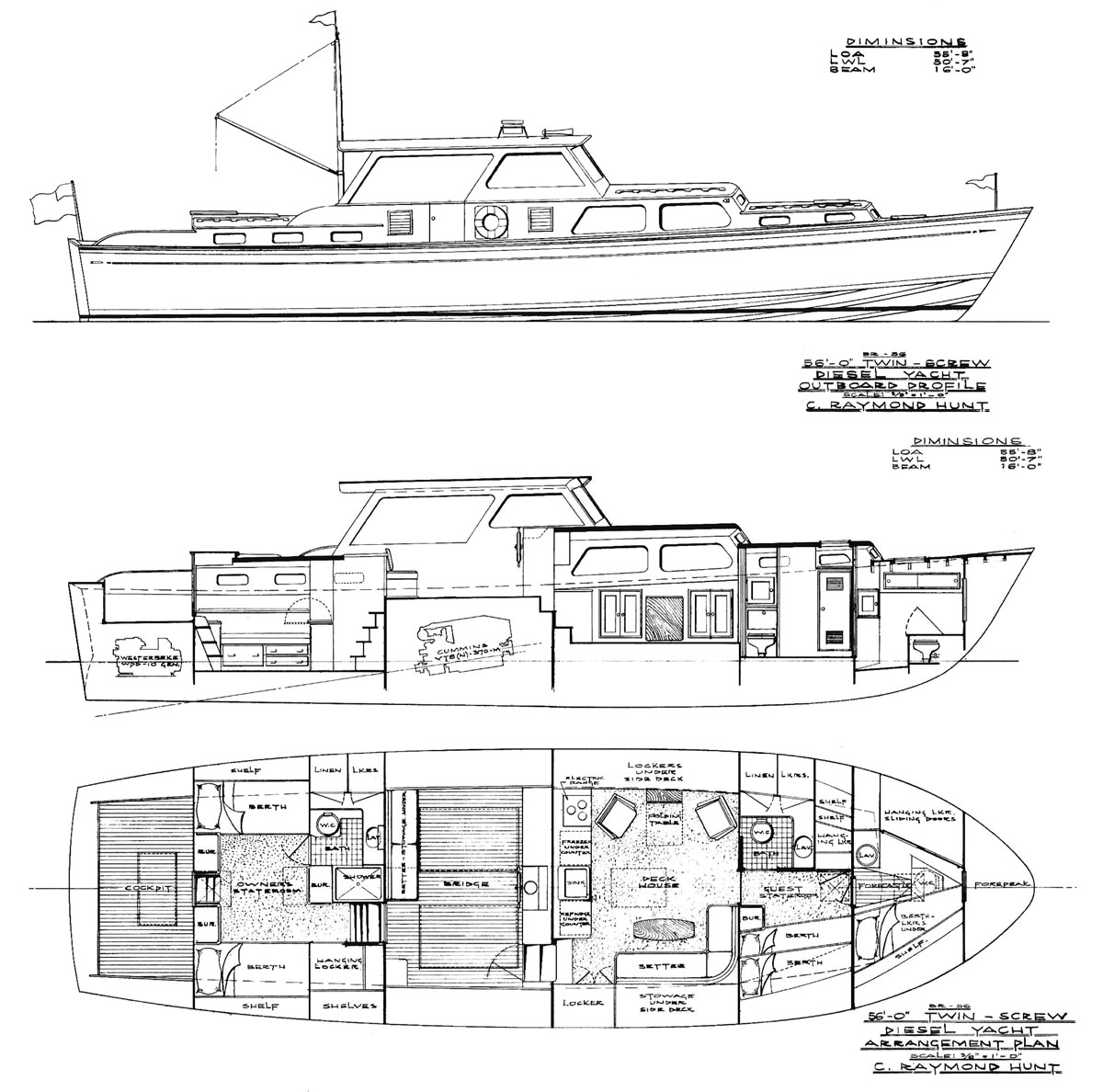

The boat was built at the Wharton Shipyard (now the Jamestown Shipyard) in Jamestown, Rhode Island, the same facility that had built Hunt’s deep-V prototypes. In its July 1964, issue, Yachting described STING RAY V like this: She “is the largest pleasure boat ever built to this design in the U.S.A. [She] incorporates the Hunt patented high deadrise hull with lift strips. [She is] framed in white oak, she is double-planked with ⅝″ mahogany over ½″ cedar. Her deck and trim, both interior and exterior, are teak.”

The yacht’s interior layout provided privacy for two couples. There was an aft cabin and a forward cabin, each with its own head, while the forepeak had a berth and toilet for a paid hand. The two living spaces were separated from each other by the helm area (unlike YONDER, STING RAY V had an enclosed helm) and a spacious combined saloon-galley that provided a common space. An aft cockpit offered pleasant open-air lounging.

Among the boat’s most prominent design features were her many windows and ports, a reflection of architectural tastes of the time. An observer viewing STING RAY V bow on could not help but be impressed by the three levels of glass: fore cabin, main saloon, helm area. The many ports and big windows allowed in plenty of light and air. As time went on, however, keeping everything watertight would prove to be challenging.

BILLY BLACK

Forward of the main saloon, labeled “deck house” on the original plans, is the guest stateroom with upper and lower berths and a head. Just forward is the forepeak with a V-berth originally intended as quarters for a crewman. Owner Holt Massey says the V-berth is now a cozy favorite of children lucky enough to sleep aboard STING RAY V.

No one today recalls what debate, if any, was involved with engine selection. Since there was no doubt but that she would be diesel driven, the choice largely came down to Detroit Diesel or Cummins (the latter would soon challenge Detroit in a lawsuit alleging patent infringements). Although Detroit was promoting to the marine market—in fact, in 1965 Bertram would win the Miami–Nassau Race and set a diesel speed record in his Hunt-designed BRAVE MOPPIE powered by twin Detroit Diesels—the decision was made to go with a pair of 370-hp Cummins VT8 (N) engines. These V-8s, which had found a military niche as power for tanks, were installed beneath the helm area, contributing to the ideal weight distribution Hunt knew was key to his deep-Vs’ performance. A 12.5-kW, 110-volt Westerbeke generator was mounted beneath the aft cockpit.

Deknatel remembers Brewster as “very fussy, a man who paid close attention to details. He wanted the boat to be as well-detailed as a Trumpy.” Ultimately, Brewster was not entirely satisfied with his new boat as delivered. He promptly took her to the Rybovich yard in Florida for detailing. “I’m not sure what they actually did,” Deknatel said. “I believe they replaced a few pieces of teak and did some revarnishing here and there.”

As things developed, Brewster’s quest for perfection in his new pride and joy was short-lived. He died in 1966, after just two years of ownership. Now commenced STING RAY V’s long voyage under a succession of owners. Sometimes she was blessed with stewards who understood her and could afford to maintain her to a high standard. Sometimes she suffered neglect. But having her was an experience that none would ever forget.

STING RAY V’s second owner was a wealthy yachtsman named Norman Francis Baldwin. He held a master’s license for all seas, sail and power. As a young man, he had captained big yachts. Among them was said to be the former Swedish Navy training ship SEA CLOUD, the 168′ square-rigger then owned by Samuel Gubelmann, whose pioneering work in the development of the portable typewriter and calculating machines had made him immensely wealthy. During the war, Baldwin had held a variety of Navy jobs, including supervising the repair of naval vessels in Miami. “Norm was,” said Dave MacPherson, back then chief engineer of the Danforth Company, “one of those people I crossed in my life who made a big impression.”

Baldwin and MacPherson became acquainted in the late 1970s when Baldwin contacted Danforth to discuss the problems he was experiencing with the macerating toilets he’d installed in STING RAY V. They were manufactured by Danforth to a design the company had acquired that promised far more than could ever be achieved. Replacements were made. With the problem resolved, Baldwin told MacPherson that he was a big fan of Danforth anchors. That led to STING RAY V being chartered by Danforth for use in anchor testing and troubleshooting.

COURTESY OF C. RAYMOND HUNT ASSOCIATES

These drawings accompanied an article about STING RAY V published in Yachting in July 1964. The basic layout remains unchanged, but the yacht has been significantly upgraded over time. The hull is framed in white oak and double-planked with a ½” cedar inner layer and a 5/8” mahogany outer layer. Decks are teak. Originally fitted with Cummins V-8 diesels, the boat is now powered by the latest Cummins QSC-8.3-600 engines. They feature 4 valves per cylinder, are turbocharged and after-cooled, and can develop 593 hp at 3,065 rpm.

“Norm had a lovely home in Key Biscayne,” MacPherson remembered. “We built a dynamometer rig for the boat’s bow and conducted pull tests on the reef in Key Biscayne, the grassy bottom of Chesapeake Bay, the sand bottom near Oyster Harbors on Cape Cod where Norm had another home, and in the mud and shingle in Maine. The engines could develop 8,000 lbs of pull in reverse that allowed us to test anchors up to 30 lbs.”

Collective memory suggests that Baldwin cruised extensively in the Bahamas and journeyed seasonally between Key Biscayne and Cape Cod. But Baldwin’s days with STING RAY V ended when he became ill with cancer. He sold the boat to a friend, around 1982, and died in 1983. The boat’s history during the next several years is indistinct. But by the time Phil Long, who was then proprietor of Renaissance Yachts in Thomaston, Maine, purchased her in about 1990, her condition had deteriorated.

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

Visibility from STING RAY V’s helm is excellent. An ingenious, wheel-operated system opens and closes the split windshield. Upgraded wipers have water nozzles to clear salt residue when necessary. The Chelsea clock is original, but the instruments, each bearing the outline of a graceful stingray, were custom-ordered by the current owner, Holt Massey.

Boatbuilder John England, who worked for Renaissance Yachts at the time, well remembers the first of STING RAY V’s several major refits. The new owner’s first decision was to address bottom problems. The bottom seams were reefed out and rotten spots were repaired. Then the bottom was sheathed with a layer of 3/8" marine plywood set in epoxy. “The plywood was put on in strips between the strakes,” England said, “and each strake was then built up with a strip of plywood to maintain their height.” Finally, the bottom was covered in two thin layers of fiberglass. England said that much of the yacht’s interior was rebuilt and some structural and deck work was conducted along with replacements for some of the interior’s decorative stingray carvings. During this refit, the Cummins engines were replaced by supercharged Detroit Diesels.

With her new lease on life, STING RAY V was sold to an owner whose wife did not approve. The result was that STING RAY V entered another period of neglected maintenance during which her brightwork fell into disrepair and topside leaks developed. That was STING RAY V’s condition when a businessman, boat lover, and admirer of Fenwick Williams’s catboats named Bayne Stevenson heard about her in Fort Lauderdale in 1991.

“At the time,” Stevenson said, “we had a Jarvis Newman 36 with a beautiful yellow-pine interior built by Concordia. But she wasn’t roomy enough, and when I heard about STING RAY, I bought her for $190,000.” In rather short order, the brightwork was repaired, two new deck boxes were built, and Stevenson and his wife set off for the Bahamas West End. “I was told not to push the supercharged engines over 1,700 to 1,900 rpm,” Stevenson said. “That was no problem, for she ran comfortably at that speed. The boat had been air-conditioned, and with her reasonably shallow draft, she was perfect for the Bahamas. When we took her to Man-O-War Cay, people remembered the STING RAY. They said, ‘You have Mr. Baldwin’s boat.’”

Subsequently, Stevenson kept the boat at Boca Grande, Florida, and made 12 round trips there from his summer mooring in New Hampshire. During this period, the boat was cared for by Elmer Dion’s yard in Kittery, Maine, and it was there that the white hull was repainted fighting-lady yellow. In 1994, STING RAY V was judged best-in-show at that year’s WoodenBoat Show at Southwest Harbor. The Stevensons enjoyed their boat for more than a decade until 2003, when they sold her to a Boca Grande friend. This was Frank Hagerty, genial founder of the insurance company specializing in antique automobiles and yachts.

BILLY BLACK

A sense of airy spaciousness and good outward visibility were goals of Ray Hunt and his designers. The spacious saloon remains fitted with the curved-back settee specified on the original drawings.

“Dad would salivate over that boat,” remembered Hagerty’s son McKeel. “Whenever I’d visit, he’d say, ‘You’ve got to come see STING RAY.’ After he bought it, we spent a lot of time with Bayne learning the boat.”

Not long after that purchase, one of the engines became inoperable. The boat was trucked to Traverse City, Michigan, where both diesels were rebuilt in situ, a difficult process that required removal of the pilothouse and deck. “We really should have repowered,” McKeel said, “because those Detroit Diesels weren’t refined enough for the boat and were deafening at speed. But we cruised the Great Lakes and she was a show-stopper wherever we went.”

Hagerty kept STING RAY V until he became ill. Then, in 2009, she was sold to Brooklin (Maine) Boat Yard owner Steve White. “Initially,” White recalled, “the idea was that a customer of ours would buy the boat. But the survey revealed enough wrong that he decided not to. But it was a great design and I decided to go ahead myself and make it a shop project.”

By now, STING RAY V was 45 years old and showing her age. When the boat was hauled, it was evident that the keel needed closely spaced blocking to keep the hull from sagging. Among the first structural changes was to improve the yacht’s longitudinal strength. The floor timbers were bolstered with Douglas-fir reinforcements, and the keelson itself was beefed up. “We made a big I-beam out of the keelson,” White said.

The Detroit Diesels were removed and sold to local fishermen. After consultation with C. Raymond Hunt Associates, the latest Cummins diesels were installed. These inline six-cylinder engines can produce 593 hp at just over 3,000 rpm and offer a level of sophistication, lower noise levels, and performance undreamed of when STING RAY V was built.

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

Generous flare and the forward ends of the distinctive lifting strakes developed by Ray Hunt are evident in this image of STING RAY V at speed. The yacht embodies the level ride, directional stability, and ability to maintain speed in rough seas for which the Hunt deep-V is renowned.

White estimates that some 21,000 hours were spent on the restoration, during which the entire yacht was thoughtfully upgraded. The work list, ranging from new bronze rudders to new aluminum fuel and water tanks, new canvas for the pilothouse enclosure, and a re-paint, provides ample evidence of the demands a yacht such as this one imposes.

After selling the boat, White got to experience her at sea with her new owner and his professional captain. “The boat is very smooth-running and able in big seas and a headwind,” he said. “Her new owner did some extensive cruising during the five years he owned her.” For a time during this period, STING RAY V found a home rather far from saltwater on the Tennessee River at the Chattanooga Yacht Club. Then she was sold again.

Northrop & Johnson’s Jonathan Chapman handled the sale for Steve White and has by now brokered STING RAY V three times. “The boat has always sold relatively quickly,” he said. “I attribute that to her fantastic design and because she handles beautifully and is easy to maneuver in and around a dock. There’s not a lot of windage. Where you put her, she sits. And there’s 360-degree visibility. Offshore, she gives a dry ride and doesn’t roll or wallow. She’s on step at 13–14 knots and 18–21 knots is her sweet spot. She’s just a unique boat.”

In November 2014, Holt Massey purchased STING RAY V after seeing the yacht at the Fort Lauderdale boat show with his son David, who is a naval architect. “We looked at a lot of boats,” he said, “and certainly weren’t looking for anything like it. I’d never owned a wooden boat. But when we sat down to think about all we’d seen, we came to the same conclusion: STING RAY exactly fit our needs. The two cabins, two heads, saloon, and forepeak, made it perfect for adults with children.”

Massey, whose business involves restoring antique buildings in Boston, was quick to recognize the boat’s historical aspect. “When I mentioned the possibility of buying STING RAY to a friend, he told me he’d often seen her in the Bahamas and that she was quite a famous boat. I made a low offer and the boat has been a joy ever since.”

But in the five years since STING RAY V had left the Brooklin Boat Yard, a number of issues developed. A water tank leak resulted in rot in the bottom planks at the transom. Repairs were made while the boat was still in Florida. Then Massey brought the boat to New England, where much additional work was carried out at New England Boatworks in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. There, not very far from where she’d been built, STING RAY V began to be updated under the supervision of Dave Resare, proprietor of Starboard Marine in Bristol.

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

As originally built, STING RAY V did not have a swim platform, transom door, or decorative carving on the stern. The beautifully crafted deck boxes offer handy storage space while the aft cabin and cockpit provide both privacy and a comfortable lounging space.

“When I first saw her,” Resare said, “I knew this was a project I wanted to take on. And it’s nice to have a client with an appreciation for the classic.”

The boat’s forward-facing ports had been eliminated at some point, but the many remaining hatches, windows, and ports were leaking. “None of them were original to the boat,” Resare said. “The ports were aluminum, and not the higher-end versions at that. We replaced them with high-quality stainless-steel units.”

It also was evident that water had been seeping beneath the yacht’s trim pieces and hardware. All the windows, ports, rails, trim, ventilators, and spotlights were removed, along with other hardware, and all the mounting holes were allowed to thoroughly dry out. Then everything was reinstalled with bronze fastenings and new bedding compound. Some 500 bungs were involved when it came time to complete installation of various trim pieces. A large section of the pilothouse roof was replaced. A bad odor in the main cabin was eradicated with the replacement of the holding tank and hoses. The next project will be to bring the wiring up to the latest standards. As things stand, the yacht is on track to become better than new, and Massey intends to maintain her progress by conducting annual surveys.

In aesthetic terms, STING RAY V now represents an intriguing blend of mid-20th-century modern design, traditional touches, and the latest in marine engine and electronics technology. Comparing her hull to a contemporary deep-V of similar length, Deknatel said: “STING RAY’s hull represents the refined first generation, better strips, and full deadrise. The current evolution responds to the increased weight of the modern boats. We have found that substantially wider chine flats and slightly less deadrise aft improved weight carrying without impacting seakeeping or performance.”

Owners of Ray Hunt boats sometimes say they feel a uniquely personal connection to the designer himself. I’ve heard this too often from owners of 110- and 210-class sloops, as well as Concordia yawls, to ever doubt it. Massey is now a member of this appreciative group. Out of the hundreds of modern boats he walked past three years ago at the Fort Lauderdale Boat Show—yachts that would offer higher speeds and the latest in design and creature comforts—it was a one-off Ray Hunt deep-V that spoke to Massey. “She’s just a real dream for me,” he said. It seems likely now that STING RAY V will sail on, bearing Hunt’s personal touch and his deep-V legacy with her, well into the foreseeable future.

Stan Grayson is a regular contributor to WoodenBoat. His biography of Ray Hunt, A Genius at His Trade, is available from The WoodenBoat Store.