The Mayor of Joe’s Sound

The Mayor of Joe’s Sound with supper (a beautiful, mature queen conch).

On March 26, 2012, I set sail from George Town, Great Exuma, Bahamas, for Cape Santa Maria, the north end of Long Island, about 25 miles away as the seagull flies. I was sailing in my sharpie schooner IBIS, with Canadian Joee Sym as first mate. Because this was a windward passage, and because IBIS is flat-bottomed with a centerboard, it was a somewhat rough beat to windward, and we motorsailed to get there early enough to seek out a good anchorage.

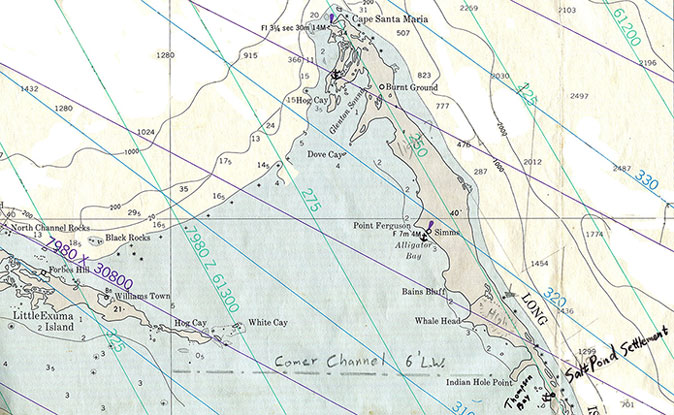

Chart for the passage from Great Exuma to Long Island.

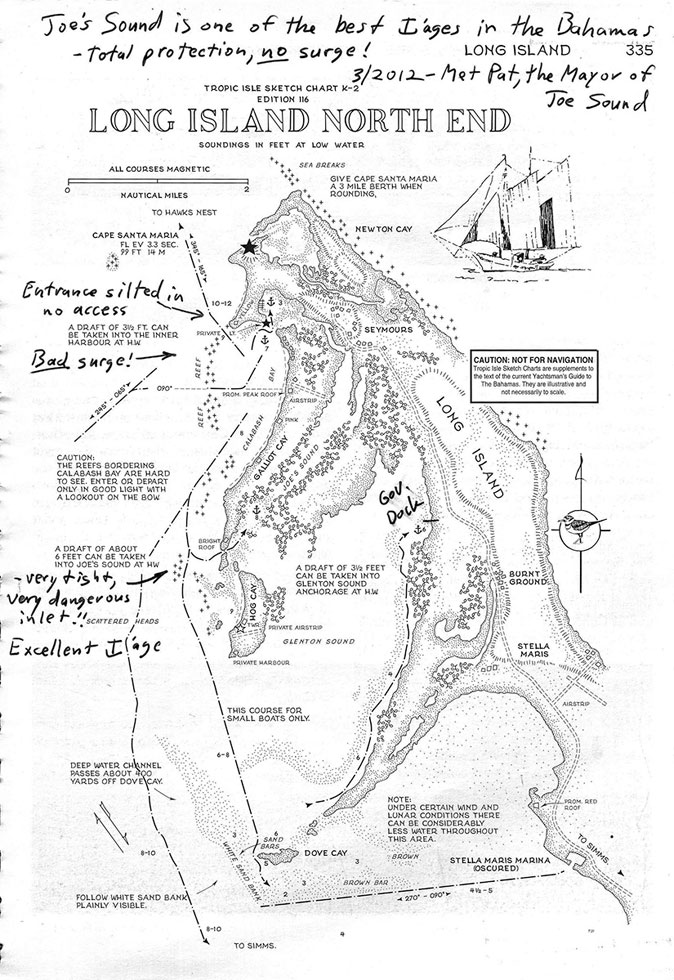

We initially anchored just below the Cape, in its lee, but the large ocean swell wrapping around the top of the Cape rolled us so hard that we had to get out of there. We tried to enter a small, protected inner harbor that my trusty Yachtsman’s Guide to the Bahamas (Harry Kline’s old guide) indicated we should be able to enter with our 2 ½-foot draft, but the entrance was silted in (see sketch chart below).

We had been told by cruisers back in George Town about Joe’s Sound—a shallow estuary about five miles south of Cape Santa Maria, with a hard to see, somewhat tricky entrance between two dangerous rocky cays. With very little daylight remaining, we cruised along the shoreline looking for the entrance, and the only thing we saw that could be it was so hairy I couldn’t believe it! “Somewhat tricky?!?”

The Entrance to Joe’s Sound, looking out from inside—the dark water colors indicate sharp rocks just inches below the surface—the turquoise channel runs from left (outside) to right (inside), and involves a zigzag series of turns.

Entering the inlet involved approaching the rocky shore just to the south, avoiding a brown patch of very sharp rocks just inches below the surface, zigzagging around a similarly dangerous shoal extending from the north side, running dangerously close to the rocky shore on the south side (in strong winds and big swell), approaching very close inside the exposed rocks immediately to the north, hugging the rocky north shore to avoid another shoal extending north from the south shore, then hanging a sharp left into the Sound! My notes in the Log state: “tight sphincter—worst inlet I ever did!!” And I have navigated almost every inlet on the east coast of the United States—from Halifax Nova Scotia to the Dry Tortugas of the Florida Keys, including dozens of inlets in the Bahamas. I didn’t have time to register the depth—I was too busy watching the rocks to look at the depth sounder. The channel was maybe thirty feet wide, and shallow, with a rocky bottom. Navigating shallows in the Tropics is done by eyeball—the depth sounder is rarely involved. By the time you even look at it, it may be too late! You have to read the bottom by eye. A bow-lookout is usually essential—one who knows what they are doing, using well-rehearsed hand signals. IBIS’s draft of 2′ 6″ gave us fantastic freedom and access.

The south part of Joe’s Sound, looking west from Hog Island—at low tide the dark turquoise channel carries four feet of water, and the light turquoise water one foot.

The sketch chart below, from Yachtsman’s Guide to the Bahamas, shows the kind of dangers the cruiser must cope with in exploring the beautiful waters of the islands. The “plus” marks designate hard, rocky reefs just below the surface. The last part of the old Bahamian riddle says “brown, brown, run aground.” A draft of three feet or less is ideal for “gunkholing” here. A draft of four or more feet will have limited access to many of the most remote and beautiful anchorages. For example, the entrance channel to Calabash Bay shown below, runs right through a narrow opening in the reef. There are no lights, no channel markers, and no range markers. To enter here, you must have good light to “read” the bottom and stay in the channel. This is typical of navigating everywhere in the Bahamas. Kline’s aid for the channel is to take a 90-degree magnetic compass bearing on the house on the beach, and follow that line into the bay. Hopefully that house survived the last hurricane!

Harry Kline’s sketch chart from The Yachtsman’s Guide to the Bahamas for Northern Long Island—soundings are in feet

Once inside Joe’s Sound, we were in calm, still waters, protected from waves and swell, but with enough wind to keep the mosquitoes and no-see-ums at bay. It was beautiful! There were maybe a half-dozen boats anchored in the Sound—mostly small multihulls—but with a couple of powerboats and shoal-draft sailboats. Parts of the Sound were a few hundred feet wide, and parts were narrow mangrove channels. There was 6 feet to 8 feet of water in a “hole” near the south end, shoaling to much less trending north.

IBIS anchored in the tidal channel near the middle of Joe’s Sound—while the channel carried four feet of water, it was very narrow—and the water on either side carried less than a foot at low tide—as evidenced by the mangrove saplings

A rare conch.

Anchored near us were a small sailboat and a modest houseboat. The owner of both rowed over to bid us welcome, and introduced himself as “the Mayor of Joe’s Sound.” Pat, then 60 years old and looking 40, is the captain of an Alden wooden charter schooner working out of New York in the summer, and living the idyllic life of a vagabond sailor in winter. He spends most of his time diving, and took my first mate Joee out to the reef next morning to stock up on the best seafood in the world!

Joee snorkeling for supper.

They came back with conch, fish and lobster (spiny crayfish), and we ate like royalty for a week. They even speared a lion fish—a very dangerous invasive species which has poisonous spines and no serious predators—supposedly very tasty, but risky to clean!

Pat with “bugs”—Bahamian lobster.

We stayed for two days, swimming, diving and going for long walks along the beach and local roads. We saw almost no-one. This is one of the quietest and most peaceful places anywhere, and I could see why Pat lives here half of each year, to offset the intensity of running a charter schooner in New York.

Joe’s Sound, with my 18th-century Swedish periagua tender on the beach of Hog Cay

We departed Joe’s Sound on March 29, and sailed south along the pristine west coast of Long Island for a week of living in paradise. I had never done this before, having only cruised the windward east coast thirty years previously (1982) in my deep-draft cutter FISHERS HORNPIPE. The Bight of Long Island is very quiet and peaceful, with very few other cruising boats in evidence, even though there are at least a half-dozen beautiful, protected anchorages. There are miles of perfect beaches with occasional settlements having stores, bars, restaurants and marinas—everything I could want or need. I even found Wi-Fi (a mixed blessing)! You had to buy a drink to use it for free….

If fate is kind enough to allow me to build and cruise in another boat (I sold IBIS in late 2013), I will definitely return to Long Island, and to Joe’s Sound—and I hope to find the Mayor alive and well.

12/4/2014, Saint Lucie Village, Florida