A Sound Boat and Simple Living

Reflections on 10 years of voyaging in a traditional wooden boat

Reflections on 10 years of voyaging in a traditional wooden boat

JAY JOHNSON

Bruce, Tiffany, Seffa Jane, and Solianna (with conch shell) enjoy an evening sail.

Bruce Halabisky

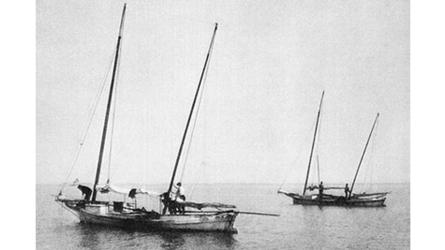

Bruce Halabisky and Tiffany Loney departed British Columbia ten years ago in their 34′ Atkin cutter, VIXEN. During their ensuing circumnavigation, they had two daughters and uncounted adventures while living on a modest budget. VIXEN is shown here off West Maui, days before departing for her return to B.C.—her first time there in a decade.

Forty days after leaving Costa Rica, I stood on VIXEN’s foredeck and scanned the western horizon of the Pacific Ocean, hoping to catch a glimpse of Mauna Kea, Hawaii’s nearly 14,000′-tall volcano. Onboard were my wife, Tiffany, myself, and our two daughters, Solianna (eight years old) and Seffa Jane (four years old). In the afternoon Solianna climbed the rigging to get a better look as VIXEN sailed west, steadily closing the distance to our landfall—though there was still no sign of land. Then, just before sunset, a large cloudbank slid off to the south, and there it was, the summit of Mauna Kea covered in snow with even its astronomical observatory visible in crisp detail. The last time Tiffany and I had seen Mauna Kea had been 10 years earlier when just the two of us had left Hawaii for Tahiti.

VIXEN’s arrival in Hawaii closed the circle on what had become a 10-year trip around the world. Our two daughters had been born along the way: Solianna in New Zealand and Seffa Jane after we reached Brazil. The voyage had taken us across the Pacific and Indian oceans, and then from South Africa to Maine to Senegal and over to the Panama Canal on a circuitous route that involved three Atlantic crossings. Every year had been filled with adventure, rich cultural exchanges, and months of sailing our traditional gaff-rigged cutter. Along the way there had been rough weather and rolly anchorages, and moments when fear and uncertainty had overwhelmed our skill and confidence. Fortunately, we had been able to put these challenges into perspective, and the good times and the good weather had always returned. It was an economically sustainable lifestyle that we could continue indefinitely if we chose to. Somehow, all the pieces had come together to make for a successful extended voyage.

Bruce Halabisky

While VIXEN traveled to some of the most remote places on Earth, she also visited some of the most populous ones. Here, she lies at anchor in downtown Brisbane, Australia.

The next day, after sighting Mauna Kea, we sailed VIXEN into Hilo Harbor and dropped anchor in Radio Bay behind the breakwater almost exactly where we had anchored 10 years previously. I started thinking about all of our friends on boats who had cut short their own trips around the world (or never even started), and I wondered what was really necessary for a successful life of ocean voyaging. To focus things, I came up with three categories: the boat, the crew, and the economics.

The Boat

In today’s world of cruising boats, VIXEN—a 34′ plank-on-frame gaffer—is an anomaly (some might even say an absurdity!), but in explaining this element of our successful voyaging life I will go out on a limb and say that she was the ideal boat for the journey. First, it must be explained that although VIXEN was launched in 1952 and circumnavigated for the first time later in that decade, she had a major rebuild during the 1990s; by the time I bought her in 2002 she could have been considered a new boat. As a result, in the 13 years I’ve owned her, I’ve done plenty of painting and varnishing but very little repair to the boat’s wooden structure. This is normal for a new wooden boat; there is no reason to be replacing planks, frames, or any other wood on a properly maintained 13-year-old boat, even in the tropics where we have spent a majority of the past decade.

What does take time on any vessel are all the pumps, electric motors, diaphragms, impellers, and filters that make up the systems of a modern boat—and VIXEN has relatively few systems. Only twice have I had to repair any wood on VIXEN, and both were inexpensive fixes: Once in Fiji, while hauled out for bottom painting, I replaced the worm shoe. This required just a taxi ride to a local sawyer and about $20 for an appropriate plank. In Brazil, VIXEN’s tiller sheared off at the rudderhead while she was berthed in a marina when a yacht backed into us at full throttle after its propeller spun off the shaft. Again the repair was easy: a local woodworking shop had no trouble making a new tiller out of readily available tropical hardwood. VIXEN is a simple boat. She has no radar, watermaker, refrigeration, roller-furler, or inflatable dinghy with outboard motor, and this simplicity helps keep our maintenance expenses down. This simplicity, combined with her small size, means that she requires no more work, and probably less work, than the average cruising boat.

Bruce Halabisky

Solianna pays tribute to the Statue of Liberty in 2011.

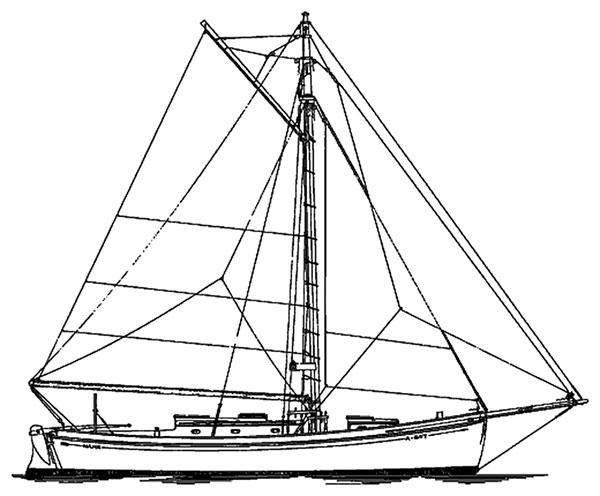

A common complaint of the gaff rig is its poor performance upwind. However, when William and John Atkin designed VIXEN in 1950 it was specifically with a circumnavigation in mind. Such a voyage, for the most part, means lots of downwind tradewind sailing, and VIXEN does this very well. It is true that by having a long boom rather than a tall mast, the gaff rig forgoes the long luff necessary for good upwind performance. Combined with the boat’s long, straight keel, the low-aspect gaff has an astonishing ability to hold a long downwind course. VIXEN carries no self-steering gear other than a simple sheet-to-tiller system (see WB No. 221).

The gaff rig offers a degree of safety difficult to achieve with a slender marconi rig. It’s a low-tension, heavily stayed rig and is resilient to knockdowns or—in a worst-case scenario—dismasting when hit by a squall. On several occasions we’ve been struck by winds of 50 or 60 knots but have remained upright because she just doesn’t have the sail area high up to leverage her down. (This may be one reason Atkin designed VIXEN without a topsail.) I mention this because a serious knockdown has precipitated the end of many a world cruise not only because of the physical damage it can inflict, but also from the crew’s psychological realization of the boat’s inability to stay upright. A sound, safe boat is essential to any successful voyage.

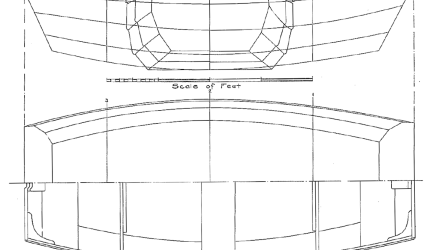

One other safety factor worth mentioning, because I haven’t seen it written about before, is the ability of a deep-bodied traditional vessel to remain safely at anchor due to its low freeboard and windage. VIXEN, for example, has 6′8″ of interior headroom throughout her 10′-long cabin while showing only 2′3″ of freeboard above the waterline amidships in addition to 1′7″-high cabin sides. This amount of headroom with such low freeboard is only achievable because we are living deep inside the boat, almost on top of the ballast. A similar-sized fin-keeled sailboat needs higher freeboard or a built-up cabin (or often both) to achieve an equal amount of headroom. The result is that a modern fin-keeled sailboat has a large amount of windage—much of it up forward—which, besides being unsightly to the traditionalist, makes the boat difficult to keep at anchor when the wind pipes up. A deep-keeled traditional hull stays put like an arrow into the wind; the high-sided fin-keeler tacks back and forth and tries to pull her anchor from the seabed with a cycle of ferocious jerks. We anchored in all kinds of situations during our circumnavigation, and VIXEN has almost never dragged anchor—which can’t be said for many boats. I attribute this not so much to our skill or anchoring gear, which is robust, but rather to the boat’s low profile and not “tacking” at anchor.

Bruce Halabisky

Solianna and Seffa Jane dress for a recent downpour while at anchor.

Even as I write these words, I realize few people will choose to go to sea in a traditional wooden gaff-rigged boat, but that is all the more reason to explain what has worked well for us. The important points are to get a boat that is safe in all weather, and to get one that is not too big or complicated for your budget—or for your crew.

The Crew

I’ve always been careful to define our trip on VIXEN as an adventure and not a vacation. For one thing, we are working along the way, so it can hardly be called a vacation. More important, an adventure implies that a certain amount of physical discomfort is to be expected in exchange for the physical experience. This is an important distinction, because if cruising is viewed as a kind of vacation, it calls for a totally different boat and economic situation than a cruise that’s viewed as an adventure. It is possible with today’s technology to replicate most of the comforts of land on a boat, but it will require a fairly expensive and complicated boat to do so. Basically, Tiffany and I were expecting to rough it and forgo some of the luxuries of a life on land in exchange for traveling and seeking new experiences.

Tiffany Loney

Bruce shares the cockpit with a group of visitors while anchored at a remote atoll in eastern Indonesia.

When we left we were in our early 30s, and by luck that turned out to be a good age to go on an extended voyage: We were both old enough to have developed useful skills that allowed us to earn money, but we were young enough to not have any health issues. Just as important, our parents were in good health, so caring for them was not a worry. We were also fortunate to have two daughters born along the way, which added a rich dimension to exploring in VIXEN. It might be argued that we jeopardized our future by going sailing during a decade when friends our age were saving for retirement and paying off mortgages, but when I think of all the incredible places we’ve been and the things we’ve seen over the past ten years I really can’t imagine that the time could have been better spent.

We have occasionally taken on additional crew members to help on long passages, but they have usually turned out to be more of a liability than an asset. Life at sea can be adventuresome and beautiful and inspirational...but it can also be mentally strenuous, physically uncomfortable, and downright scary. Crew members need to have a rock-solid mental foundation and be in reasonable physical shape. A long night watch alone, without the myriad land-based distractions, will rustle up any demons lurking in one’s mind.

It has been interesting to observe Solianna and Seffa Jane on long ocean passages. They seem so immersed in the present that they don’t have the normal adult yearnings for land. They play with their dolls, they have lots of story time, and have a general attitude of “Who needs land?” Four-year-old Seffa Jane, in particular, had no obvious desire to go ashore after our 41-day crossing to Hawaii.

Author’s Collection

Bruce explores the market on the island of Flores, Indonesia, in September 2008.

Another key aspect of our cruising success has been our transportable skills. Tiffany and I have been lucky to find work along the way. In fact, some of our best memories come from our time working in foreign lands—Tiffany as a yoga instructor and I as a traditional boat builder. Some of my friends who are builders have told me that they could never be away from their trade on an extended voyage because it would be so difficult to reestablish work contacts when they returned. The rebuttal to that argument is that if you are known to be a journeyman, a lot of short-term interesting work can come your way which more qualified tradespeople would have to pass up because they are locked into a steady job. I’m sure more than one employer has thought, “Oh, Bruce doesn’t have a real job, maybe he could do it.” Of course, what allows for the flexibility of working part time is the low overhead our simple lifestyle demands—which brings me to the economics of voyaging.

The Economics

For two seasons, from 2012 to 2013, VIXEN sailed the coast of Maine. By the time we left the New England coast bound for the Azores, it seemed we’d already visited more Maine anchorages than most sailors who spent decades living there. Our simple life with low overhead allowed for lots of time to sail and explore. In fact, Tiffany and I have felt spoiled with free time ever since our departure from Victoria. In 2009, for example, we spent one month in Thailand, one month in Malaysia, two months in Indonesia, a few weeks in the Chagos archipelago, three months in Madagascar, and two months in South Africa—and that kind of diverse extended travel has been fairly typical year after year. Our movements have been mostly determined not by a need to return to work but rather to avoid the hurricane seasons or winter gales and sometimes by a country’s visa restrictions. In addition to spending long amounts of time visiting many different countries and cultures, we have been able to do it as a family. Much of what we do day-to-day on VIXEN is very basic and cost-free—finding water, going to markets, cooking food, maintaining the boat, swimming, and sailing. Plus we are doing it in some interesting places, and we are doing it as a family.

JAY JOHNSON

VIXEN, fully loaded and ready for sea, romps along the Maui coastline just a few days before departing for British Columbia. As this issue was going to press, she’d arrived in B.C. after a 26-day crossing, completing a nearly 11-year circumnavigation.

And here is the amazing thing: When Tiffany added up our costs for 2009, as an example, our total expenses were just over $10,000. That’s for the whole year, for the three of us, and includes all the boat expenses (Seffa Jane had not yet arrived). Of that $10,000, $2,000 went into maintaining VIXEN and the bulk of the remainder was spent on food.

Before we had kids there was some logic to flying home, where we could find well-paying work to cover the airfare. When Solianna turned two years old, she had to pay full fare for an airline ticket, so flying home made less economic sense. When both Solianna and Seffa Jane were paying adult fares, it became too expensive for us to fly home to visit our parents. On our current budget, flying the whole family anywhere just doesn’t make sense. This is one reason we are taking a break from voyaging: We’ll be keeping VIXEN closer to our extended families.

During our voyage, our annual budget has consistently been between $10,000 and $12,000, with a couple of years costing close to $20,000. Usually, we can earn this by working about two months every year and occasionally as many as four or five months.

It didn’t feel like a pauper’s budget while we were living on it, but by North American standards it most certainly was. In fact, most people don’t believe our numbers. But consider for a moment a lifestyle with no monthly bills—no mortgage, no car payments (no car!), and in fact no debt at all. And don’t forget having no phone, no Internet, and no TV bills, and one can begin to understand how the majority of every dollar we earn goes into maintaining VIXEN and buying food. We also have no insurance.

TIFFANY LONEY

Bruce plays a borrowed guitar on the banks of the Casamance River, Senegal.

When we cruised coastwise in VIXEN, we had her fully insured for $900 per year. To carry that same level of coverage offshore would cost about five times as much. In addition, there were requirements that the insurance companies dictated. Some insisted that three adults be onboard, and most had restrictions on where and when we could take our boat. We made the decision to not carry insurance but rather to take this money and use it to buy the best anchoring equipment, charts, and safety gear we could—things that really would make the boat safer and stronger.

Tiffany and I decided not to carry health insurance, partly out of necessity as it was too expensive, and partly from a reluctance to succumb to the fear-based mentality of insuring every element of risk in our lives. This decision was easier to live with once we left the United States, where healthcare is extremely expensive. Most of the world has a reasonable cost for high-quality care. Although we have been healthy for the most part, the occasional visit to a doctor might cost $30 to $40 outside of United States. I would guess that in 10 years of voyaging we’ve spent less than $500 on health care. If we had carried full insurance for ourselves and the boat, the voyage would never have happened. I imagined myself as a grandfather telling my grandchildren that I had always wanted to sail around the world. I imagined them asking me why I didn’t do it and I would have said, “I couldn’t afford the health insurance!”

Bruce Halabisky (both)

Left—Christmas at sea aboard VIXEN. Right—Solianna plays “store” with a group of friends in Madagascar.

Tiffany Loney

Bruce and Solianna take a taxi ride in an untouristed area of an island off Sumatra.

There is a strong tradition of uninsured human accomplishment. In fact, I would venture to say that most great accomplishments were uninsured. With the exception of the past 20 years, most ocean voyages in small yachts—from Joshua Slocum onward—have been uninsured. There may be an argument that it is not fair to our children to expose them to such risk. I would counter that this is exactly the lesson that I hope to teach them: Life is full of risk, and that risk is best confronted not with a monthly insurance payment and living in fear of the “what ifs” but rather by educating yourself, by training your body and your mind, by moving skillfully and gracefully in the physical world, and taking full responsibility for your actions.

The term “simple living” is sometimes thrown around as some kind of dreamy-eyed utopia, but the hard numbers of VIXEN’s budget have allowed for a latitude of freedom not possible if a larger income was necessary. It is a careful balance in which the boat herself is an important element. At 34′ on deck, VIXEN is small for four people to live on. With two kids aboard we are awash in children’s books, craft materials, and stuffed animals. A bigger boat might make a lot of sense, but I worry it would topple the balance we have achieved. Would I want to paint the bottom of a 45′ boat alone, as I do with VIXEN?

There are many ways to finance a sailing voyage around the world. Some sailors justify a larger boat by taking on paying crew, while some singlehanders happily cruise in boats smaller than VIXEN. There is no upper limit on how much one can spend, and the lower limit can be even lower than ours. But the fact is that the more lavish budgets do not necessarily provide a more rewarding experience. If costs can be kept down with a small boat and simple living, every dollar earned can reap the maximum amount of voyaging possible.

Bruce Halabisky (both)

Left—Three-year-old Solianna and a friend in Langkawi, Malaysia. Right—Solianna blows the conch at sunset.

VIXEN’s Voyage: Combining Boat, Crew, and Economics

The anchorage in Radio Bay is a hard-earned refuge for ocean voyaging yachts; over 2,000 miles of open ocean isolate the Hawaiian islands from the sheltered cruising grounds of the mainland. Anchored alongside VIXEN were a couple of steel sailboats that had come from Europe, rounded the Horn, and were on their way to Alaska. Just beyond them was a fiberglass double-ender that had done the Ketchikan-to-Hilo run 24 times in the past 30 years. There was even a 20′ fiberglass sloop that a young man had sailed from San Diego in 28 days. A week after we arrived, a crew of four Russians sailed in on their way from Mexico to Kamchatka in eastern Russia.

None of VIXEN’s neighboring ocean voyagers were in wooden boats or were gaff-rigged, but each of them had found some successful combination of boat, people, and economics to make the voyage happen and to keep it going. Floating next to these sea-tried vessels, her second circumnavigation now complete, VIXEN offered quiet proof that a sound gaff-rigged wooden boat with an adventurous and economical crew is a viable option for successful long-term voyaging.

Bruce Halabisky, a graduate of The Apprenticeshop of Rockland, Maine, is a traditional boat builder and sailor. He is a frequent contributor to WoodenBoat.

VIXEN

An Atkin classic designed to cross oceans

WWW.ATKINBOATPLANS.COM

Based on the double-ended Norwegian pilot boats and rescue boats of Colin Archer, VIXEN represents more than three decades of refinement by John Atkin. She is an ideal and proven ocean cruiser.

VIXEN was designed in 1950 by the father-son team of William and John Atkin of Darien, Connecticut. The commission was from James Stark of Miami, Florida, for a sailboat to take him and his wife, Jean, on a cruise around the world. Although not known for producing race winners, the Atkinses would have been a first choice to draw up a cruising sailboat in the 1950s. In fact, a complete disregard for capricious racing formulas allowed them a free hand in designing sensible bluewater vessels.

VIXEN was launched in 1952 from the Black Rock, Connecticut, shop of Joel Johnson, a well-known shipwright of the Bridgeport area. In 2011 we sailed into Black Rock and moored VIXEN just a stone’s throw from where she was launched. The Johnson yard shut down long ago, but the building shed still stands, and we were able to locate the old railway that VIXEN would have rolled down sometime in the spring of 1952.

After her launching, the Starks successfully sailed VIXEN around the world. Not much is known of this first circumnavigation, although as we have retraced VIXEN’s route, some details have emerged. John Guzzwell, who broke records for both his young age (25) and size of boat (20′6″) circumnavigating between 1955 and 1959, clearly remembers mooring next to VIXEN at the Royal Natal Yacht Club in Durban, South Africa, in 1958. This recollection was confirmed when we sailed into Durban and met Bob Fraser, who was a friend of James Stark and even had pictures of VIXEN from that visit.

We have also connected with Hilary Frye, James Stark’s niece, who remembers VIXEN from her youth while visiting her uncle. Last year Hilary served as one of our line handlers as we transited the Panama Canal. More recently, I received an email from 80-year-old Jo Brooks of Florida, VIXEN’s second owner after the Starks, who returned to me the original builder’s plate, which had fallen off and been separated from VIXEN many years ago.

From a design perspective VIXEN is similar to the Atkins other Colin Archer–inspired double-enders. She is often compared to ERIC, a well-known design of the senior Atkin. However, ERIC was designed in 1925, and there was much subtle refinement in VIXEN’s design. As John Atkin wrote: “VIXEN represents some thirty-five years’ development, observation, modification and improvement. It is my feeling she possesses most of the attributes desirable in a vessel intended for offshore voyaging and extended passages in safety and comfort. While conceivably based on the original ERIC, Stark’s VIXEN embodies most of the desirable characteristics and has eliminated most of the undesirable ones. She is fast, extremely able, and entirely capable of going almost anywhere.” —BH