The Snekke

Norway’s timeless motor launch

Norway’s timeless motor launch

SVENN DVERGASTEIN

Norway’s ubiquitous double-ended motor launch, the snekke (aka sjekte, or kogg), evolved from open sail-powered fishing boats. Today, as recreational boats, they have a variety of configurations: Some are protected by wraparound windshields, others have small cabins, and many retain their simple workboat layouts. Shown here is the fleet at Stavern, Norway’s highest concentration of snekker.

Last November, I spent a week in southern Norway bussing from one small town to the next up the eastern coast in search of owners and enthusiasts who could tell me something about the region’s ubiquitous traditional powerboat, the snekke (also called sjekte, or kogg, depending on where you are). These double-ended open motor launches have a powerful place in the collective cultural memory of those who grew up on this coast. Everyone I met, it seems, either had one in their own family or had a friend whose family had one.

In one way, late autumn is a terrible time to visit southern Norway if you’re interested in boats. The days are raw and bone-achingly damp, and darkness comes early. However, this is also what makes that season the perfect time to visit Norway in search of stories. In the sun-bleached summer months, there are too many small islands to be explored and fish to be caught for most Norwegians to want to sit still to reminisce. But in the November lull, no one seems to mind taking a protracted coffee break to dream about the brief but intense summer season.

When I told people I met along the way that I was interested in hearing about their experiences with snekker (the Norwegian plural adds an “r” to the end of the word), I was often initially met with, “Snekker? Really?” As is often the case in communities where the maritime heritage is still alive, outside interest in the commonplace can come as a surprise to the locals. It takes a little time for the typically quiet and reserved Norwegians to dredge up and share memories. But throughout my week traveling up the coast, over bowls of thick fish chowder speckled with saffron, with fingers pink and nicked from peeling kilos of just-caught, just-cooked shrimp, while blowing on spoonfuls of split pea and ham soup ladled hot from electric burners in shop corners, and cradling thermoses of strong bitter coffee against the cold on docks and piers, the stories started to roll out.

Lars Solberg

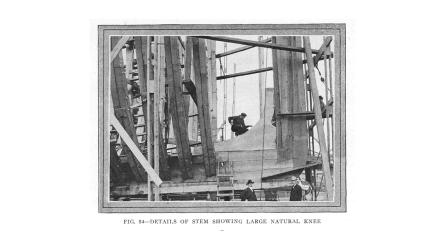

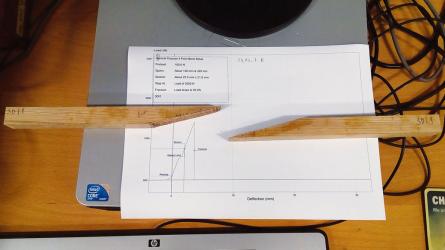

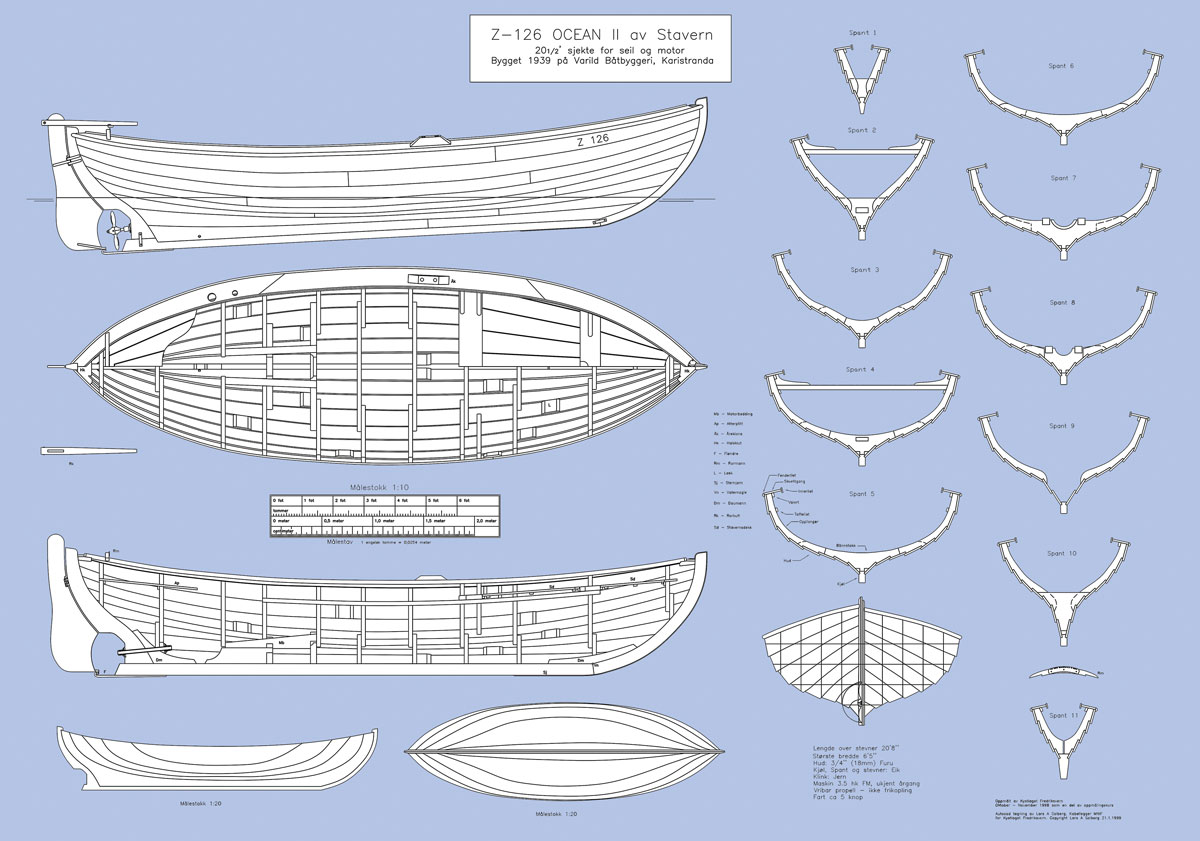

Lars Solberg, a snekke aficionado from Stavern, developed these lines for the snekker of his area. Lars has also recently published a book, Sjekteboka, detailing the history, lore, and maintenance of these boats. Additional plans can be acquired from the Norwegian Maritime Museum in Oslo (www.marmuseum.no).

Courtesy of Lars Solberg

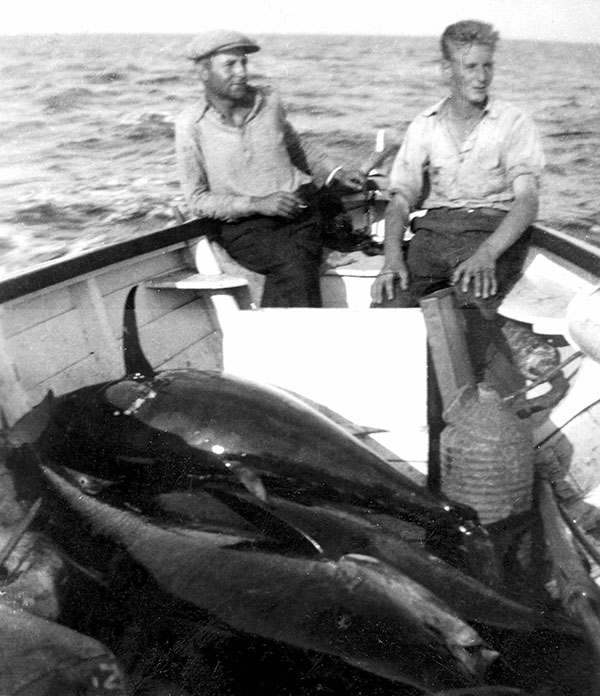

Snekke, in their working days, were multipurpose boats. They were used to fish for cod, mackerel, and salmon, to catch lobsters, and even to pursue tuna.

Snekker were once workboats, but today are pleasure boats that can be found across Norway as well as on the west coast of Sweden and in the Baltic. The type is native to Oslofjord and the Skagerrak, ranging from Mandal, the southernmost city in Norway, to Fredrikstad near the Swedish border. The modern snekke developed from the slightly smaller oar-and-sail-driven traditional workboats of the same name. With the addition of engines in the 1910s, the tiller-steered open double-enders became “motorsnekke,” which are a little longer and fuller—particularly in the stern—than their forebears, and have higher freeboard to accommodate the extra power and weight. Still, they bear a close resemblance to their ancestors. With a hull speed of 6 knots, they don’t travel much faster under power today than they once did under oar, and that’s a point of pride among owners. It is a trait that speaks to the relaxed Norwegian attitude toward pleasure boating today. It also serves as a refreshing counterpoint to contemporary motorboat culture elsewhere that is far more focused on power and speed.

Snekker embody Norwegian self-sufficiency and versatility. Historically, they were often built one at a time at home, over a winter, or a few at a time in small shops, and were subsequently used as much for subsistence as for commercial purposes. Few shops are building new snekker today, and there is no one shop that builds them exclusively. Restoration has proven to be a busier market, as it is still relatively easy to find an old fixer-upper for a few thousand Norwegian crowns. As one professional Norwegian boatbuilder ruefully pointed out to me, “it’s remarkable how long a bad boat can float if you don’t try to do anything too drastic to it.” With this attitude, many owners forgo professional restoration in favor of working at it from their own backyards. Indeed, the maintenance of both boats and engines seems to be as much a part of the culture of snekke ownership as summertime cruising.

Dag Høibø

In a typically Norwegian summertime scene, snekke enthusiasts enjoy a get-together during a raftup.

Dag Høibø

To this day, the snekke remains ingrained in the culture of southern Norway, as illustrated by these wedding-day revelers.

Modern wooden motorsnekker range in size from about 18′ to 24′ and weigh between 1,700 and 2,500 lbs (about 800 to 1,100 kilograms) without power or people aboard. They are heavily built lapstrake double-enders, usually planked in Norwegian pine or larch on 12 to 14 sawn oak frames up to 2 × 3″ in section. The ¾″ to 1″ hull planking is fastened with copper rivets and cupped roves in the Scandinavian style. In some regions, planks were fastened to frames with juniper trunnels, though today copper rivets are more common in this area. Where plank butts don’t land on frames, they are backed up with rivet-fastened butt blocks. The hulls are frequently oiled or finished bright, and the interiors are varnished or painted white for protection against the sun. Frequently, the narrow floorboards run perpendicular to the keel and are painted a deep forest green.

There is a certain flexibility in design apparent across the type. Like many historically one-off or home-built forms, they don’t adhere to any single lines plan or table of offsets. There are slight but notable variations in hull shape from fjord to fjord just in the 365-kilometer stretch of coastline from which the snekke originated. Boats built in towns where waters were relatively protected were shallower and flatter bottomed, whereas those built in towns with deep-open-water fishing fleets developed deeper V-bottomed hulls. Historically boats were built by eye with one to three molds—five is the standard today.

Lars Solberg (left), Andreas Berge (right)

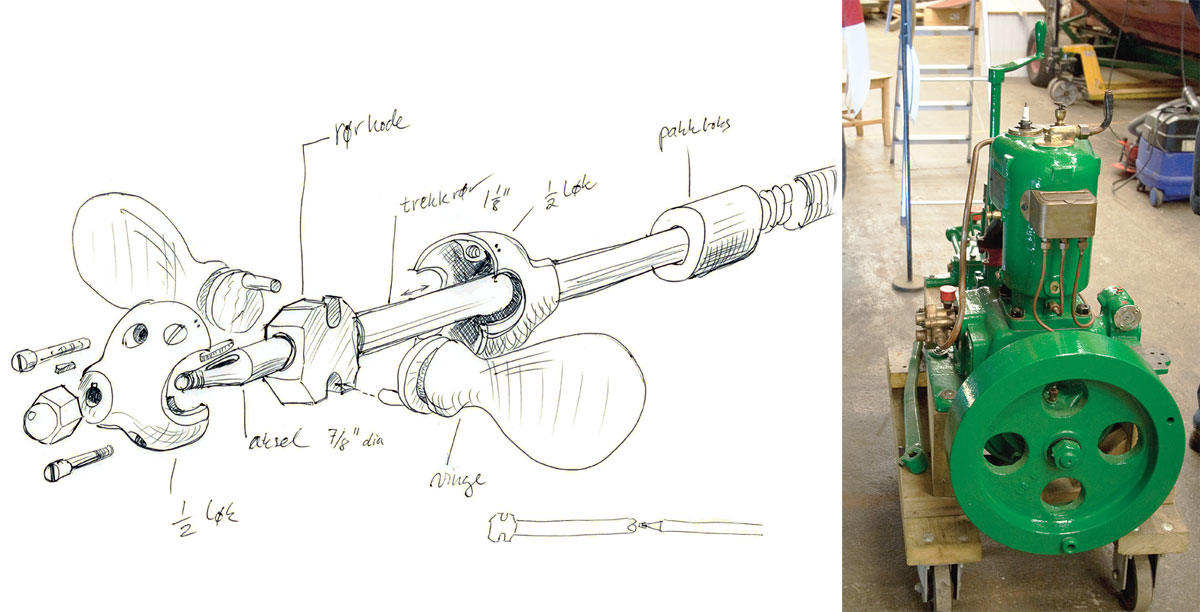

The powerplant of a snekke is a big part of its appeal. Motors (right) for the original boats were usually built by small manufacturing shops in Norway. The boats were typically built without reverse gears, and to maneuver in close quarters relied instead upon the reversing propeller mechanism shown above.

Dag Bernsten

Even open snekker provide a variety of layout options. Above is a boat with a typical “stavernsdekk”—a sunken foredeck that once provided a workspace for lobstering, and today might provide a place for a good nap. Note the mast partner: Many motorsnekker still have optional rigs.

The hulls are particularly heavily built to take the abuse of a rough and rocky coastline. But the minimal tidal range on the southern coast doesn’t require that the boats be frequently hauled or dragged up beaches out of the reach of high tides—a necessity for the boats of northern Norway, with its extreme tides. Sometimes snekker had lifting eyes fitted through frames forward and aft to haul the boats ashore with cranes when tending lighthouses.

Comparatively heavy construction is favored for its ruggedness and safety, particularly since many snekker were kept in the water to fish during the winter months. Getting frozen-in is always a consideration, and a few owners recounted stories from childhood when they were sent down to the waterfront to cut the ice from around the boats with an old lumber saw, a chore comparable to shoveling the driveway before school. One boatbuilder in Risør told me it was fun the first few times each season, sliding around on the ice with a big saw as a kid, but the novelty wore off pretty quickly. He and his siblings soon figured out that the only way to get out of it was to fall partway into the water and get soaked—but that proved not to really be worth it, either. Today, very few owners leave their boats in over the winter, despite the fact that it is rare these days for the fjords to freeze so heavily in the south that the boats need to be cut out. However, there are still an intrepid few who like to fish throughout the year, and keep their linseed-oil-coated boats in commission all winter long—in which case they might use a chainsaw to break them out after a hard freeze.

The classic antique inboard engines that drive these boats hold powerful and universal attraction for snekke enthusiasts, and their maintenance and upkeep are as important a source of pride for owners as the hull itself. Again in the spirit of “make-do” self-reliance, some of the one- or two-cylinder 3-hp to 6-hp gas-driven inboards that power Norway’s snekker were built in shops so small that the engines were produced one at a time, piece by piece, by hand. At the height of engine production in Norway in the 1920s and ’30s, there were roughly 170 shops building engines—though some only ever produced one or two. The most prolific and well-known manufacturing companies were Marna in Mandal, Fredrikstad Motorfabriken and Sleipner in Fredrikstad, and Kvikk in Stavern. In the 1940s and ’50s, engine production declined as imports, particularly from Sweden, became more affordable and began to drive the smaller Norwegian shops out of business. In the 1960s, it was cheap to take the family snekke across Oslofjord to Sweden to buy spare parts and sugar, and it wasn’t uncommon to incorporate such a trip into summer camp-cruising plans.

Dag Bernsten

The boat above has simple centerline-facing seating, which promotes easy conversation while underway. The tiller comb on the after coaming provides a quick and easy way to secure the helm while underway—a sort of primitive autopilot.

The two-bladed propellers are almost always variable-pitch props in these small boats—a fact that may surprise non-Scandinavian readers. This makes for a comfortable ride in a wide variety of conditions. With only a reduction gear instead of a reversing gear, maneuvering is smooth and efficient once you get the hang of holding onto the tiller with one hand and controlling the lever that changes the pitch with your outstretched foot. A large rudder combined with a practiced foot on the pitch control make the boats surprisingly lively and maneuverable. Another common feature is the built-in comb across the stern to hold the tiller in place—a handy and low-tech autopilot. Snekke usually carry 15–20 liters of fuel, and burn about a liter per hour in ideal conditions. One owner told me that one tank was theoretically enough to get him to Denmark from Risør on a calm day, a distance of about 100 miles. The boats run from 4 to 6 knots, and the slower the captain can run the engine, the more experienced an engineer he or she is considered to be.

The interior layout is open and comfortable and can generally be broken down into two basic variations. The first is the traditional fishing or workboat layout and includes one or two thwarts all the way forward, as well as a wet-well forward of the engine box. The horseshoe-shaped sternsheets allow for easy clearance around the motor and a comfortable seat for whoever is at the tiller—though many skippers prefer to remain on their feet for improved visibility. Many older hulls that were built to fish originally have been bought and restored as pleasure craft today, though they retain their original interior layouts. In these cases, every wet-well I encountered, without exception, was being used to store beverages. All in all, this layout is utilitarian and practical, giving plenty of space for rods or pots. It also places the crew facing forward to help with navigation.

Evelyn Ansel

A fleet of snekker is laid up for winter storage at Moen Båtbyggeriene in Risør. The range of interior layouts is represented in this photo, which shows about a third of the boats stored in that space—the majority of which are snekker.

The second variation in layout developed as summer visitors from Oslo started to show an interest in the boats as pleasure craft in the 1950s. This later style includes a small foredeck, a forward bulkhead, and an elegant rounded coaming for a drier ride. Next came the addition of windshields and eventually small cabin trunks as engines and hulls increased in size. The lore goes that in the 1950s, people began to poach windows from their basements to build three-paned hinged windshields up forward and give their boats a sportier look to distinguish them from working craft. A decade or so later, the windshields began to be produced commercially and they took on a rounder shape to give the boats a classic curvy 1960s profile.

As the foredecks and cabins developed up forward, the interior layout also shifted from thwarts to long side benches running fore-and-aft. This gave a roomier feel despite the foredeck and allowed passengers to sit facing one another—a more social and leisurely arrangement. I was frequently told also that this, combined with the slow motoring speed, created the perfect conditions for gazing into your companion’s eyes. It is no small wonder that I also heard the same stories over and over again of teenagers sneaking off with the boats and more than a few beers into the endless Scandinavian summer evenings. I have it on good authority that the ideal number of teenagers to constitute a full boat is an impressive 14, though I can’t imagine there would be much freeboard with that load.

Dag Høibø

A flotilla of snekker snakes it way through a maze of islands in southern Norway.

In my travels, I heard accounts of snekker being used to fish for everything from mackerel to herring, haddock, cod, salmon, eel, crab, lobster, and even to hunt tuna, whale, and seabirds. Today it is said that the 4–6-knot snekke cruising speed is ideal for mackerel fishing, and there are still a few traditional boats lobstering out of Stavern, but the days of tuna, whale, and seabird hunting have long since passed. Apart from fishing and hunting, snekker were also a vital means of transport in the fjords throughout the 20th century, and as people began to come around to the idea of “vacation” in the 1920s, the boats began to double as leisure craft in the summertime.

One man in his 50s recounted to me the first time his father let him take the family snekke out alone, when he was 10 or 11 years old. He was sent from the island where his family had their home to the next one over in the archipelago to pick up some “groceries”—a bag of carrots from the farm on the next island. (And yes, of course, the farmer had a charming young daughter whom the young man in question had had his eye on for some time.) This story was typical of those I heard about growing up in and around these boats in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s. The boats were used for leisurely summer camping adventures, but also carried Dad to work at a factory job across the fjord, and brought home the fish that went on the dinner table most nights of the week throughout the year. This flexibility and utility has allowed them to thrive today as recreational craft, with relatively little change to their historical form since the introduction of the engine.

Evelyn Ansel

Snekker are ideal for relaxed coastal cruising. Their rather shapely hulls have ample beam, giving them great load carrying capacity.

Everyone I met had a story about the first time they were given permission by their parents to take the boat out without supervision, just as everyone had stories about the many times they’d nearly been caught before they’d been given permission. At Midsummer, the Scandinavian holiday celebrating the solstice, the boats are decorated with greens to carry people out into the archipelago for late-night bonfires. They are perfect for anchoring out or rafting up and swimming and sunbathing off the small rocky islands warmed by the sun. A canvas cover can provide adequate shelter for overnight trips, and a tent carried in the forward bulkhead can always be pitched ashore in a pinch.

Dag Høibø

A crisp new snekke at rest. Rope fenders are a traditional piece of gear in the proper outfitting of these boats.

At night, a favorite pastime is to take lights and go crabbing out in the shallows. The sound of the engines has a nostalgia attached to it as powerful as the smell of tar and linseed oil, and the slow chuff-chuff-chuff of an engine returning in the evening is as comforting to parents as it is exciting to the kids out exploring on their own. In fact, there is so much affection, enthusiasm, and nostalgia directed toward the sounds of those engines that recordings of various types are a popular commodity on the maritime festival circuit in the summer; they are intended to be played in the car when you’re stuck on a long drive overland.

While the snekke remains popular, the greatest challenge facing the survival of the type is recruiting the next generation of young owners. Maritime heritage is still very present in Norwegian culture, but no small town is immune to the encroaching distractions of the modern world. But there is hope: These boats are heavy and slow, but that’s seen only as a benefit in some circles. “After all,” one young woman pointed out to me, “when things are as good as they are in the summertime around here, why would you be in any rush to get anywhere else?”

Evelyn Ansel recently completed a Fulbright fellowship at the Vasa Museum in Sweden, where she worked cataloging the shipwrights’ tools found with 1628 warship VASA—which sank on her maiden voyage in Stockholm.

A Builder of Snekker in Maine

It may seem unlikely that a craftsman on the tradition-steeped coast of Maine comes to be a builder of exotic, authentic Norwegian snekker, but that’s exactly what Andrew Wallace has done. Wallace, who does business as Traditional Boatworks in Eliot, Maine, has a Norwegian mother, and spent many of the summers of his youth at his family’s ancestral home in Grimstad, Norway.

Jay Fleming

Andrew Wallace, who spent the summers of his youth in Norway, today builds snekker in Eliot, Maine.

“I was a bit of a wild child,” he said. “From the time I was five years old, my mother would send me out the door at 5:30 in the morning with a local friend of hers who was a handline cod fisherman. I’d sit at the table with him in the morning and have bread and sardines and jam”—a traditional Norwegian breakfast. Then they’d head out on the water—for just an hour or two when Wallace was very young, but for 8 to 10 hours per day by the time he was 13. “He showed me how to handline for cod, from a snekke,” said Wallace, and that experience stuck with him after he’d decided to make a career of boatbuilding.

Snekker were not his first choice when he began his career. During his 1990 Apprenticeship at the Maine Maritime Museum’s Apprenticeshop, Wallace focused on skin boats—particularly the kayaks of Greenland and the Aleutian Islands. A later apprenticeship at the now-defunct John Gardner School of Boatbuilding in Maryland opened his eyes to the world of larger timbers, and rekindled those dormant memories of the snekker of his youth. With the help of his yacht-designer friend Tim Estabrook, Wallace designed and then built a snekke of his own in 2008. As luck would have it, a customer materialized for that boat at the same time.

The heavily timbered boat has 3″ × 3″ double-sawn frames—massive dimensions for a 23-footer. Per the owner’s requirements, it’s powered by a modern Yanmar diesel. It ran well, said Andrew, but it didn’t sound right. Andrew’s second boat, built on speculation with the aid of two eager and able apprentices, was more authentic: It’s powered by a 22-hp Bergen-built Sabb diesel—a 1960s vintage motor he had shipped over expressly for use in this boat. “It’ll give me another 100 years,” he said.

Andrew has built uncounted other boats of Norwegian ancestry, but he’s adapted many of them to the local requirements of Maine and New Hampshire. In this way, he’s an active participant in a 3,000-year-old tradition, in which Norwegian builders created their own local variants of particular boat types, to suit regional conditions and requirements. For example, one of Andrew’s prams, built by eye, measures 18′ overall and is powered by a 15-hp outboard motor. It looks like a traditional Norwegian boat and runs like a clam skiff. “You’ve never seen a pram go so fast,“ he said.

“Building traditional Scandinavian vessels is not the easiest way to make a living,” Andrew said. “But I’m sticking with what I’m passionate about. My mother, an old-school Norwegian—she thinks I’m crazy.”

—Matthew P. Murphy

Courtesy of Lars Solberg

The Sjekte of Stavern

One of the most notable populations of traditional motorsnekker can be found in Stavern, about two hours south of Oslo outside the city of Larvik. Stavern has the largest single fleet of snekker (called “sjekte” in this region) in Norway. At the height of summer, some 60 traditional sjekte tie up in the town’s canal. The beautifully maintained boats are a well-deserved point of pride for the locals. They are unique among Norway’s snekker not only in their number but also for their particular design and construction details. A true Stavern sjekte has no foredeck or windshield; it retains the fishing layout featuring two thwarts and a wet well/bench forward of the engine box, and U-shaped sternsheets aft. But the most distinctive design element is the “stavernsdekk” up forward. This removable deck consists of carefully fitted planks running fore-and- aft between the two thwarts and on to the bow. Historically, it provided a platform for hunting tuna as well as clear space to lay out the harpoon and gear. When not fishing for tuna, the decks served as a staging area for lobster pots. Today an intrepid two of the Stavern fleet are still hauling pots during the October-to-December lobstering season, but for the rest of the fleet, the decks are more often used as an excellent platform for summer sunbathing.

—EA

Dag Høibø

Stavern has long been a stronghold of the snekke. The top photo shows the canal there as it appeared in 1947, with snekke lining its lefthand side; in the photo above we see it in more recent years.