Thomas Clapham and The Roslyn Yawl

In the late 19th century, the sharpie type of inshore fishing boat began to insinuate itself into the world of yachting. In addition to the obvious qualities of speed and shoal draft, the low cost and simplicity of sharpies encouraged a new breed of yachtsman, who previously had not been able to afford anything that might be called a “yacht”.

The Roslyn Yawl MINOCQUA under sail in the 1890s—note the “balance jib” (photo courtesy of Gordon E. Hurley, Jr.).

As sharpies evolved into yachts, various modifications of hull and rig were employed that might have been considered “improvements” over the original fishing, oystering and crabbing models. A number of innovative designers and builders got into the act, and some remarkable vessels resulted.

One of these men was Thomas Clapham, from Roslyn, Long Island, New York. While the true sharpie hull is flat-bottomed, Clapham created a hull with moderate, fairly constant deadrise from amidships aft, and with increasing deadrise from amidships forward. While these modifications created a whole new animal in marine architecture (the V-bottom boat), Clapham called his invention a “Non-pareil Sharpie”.

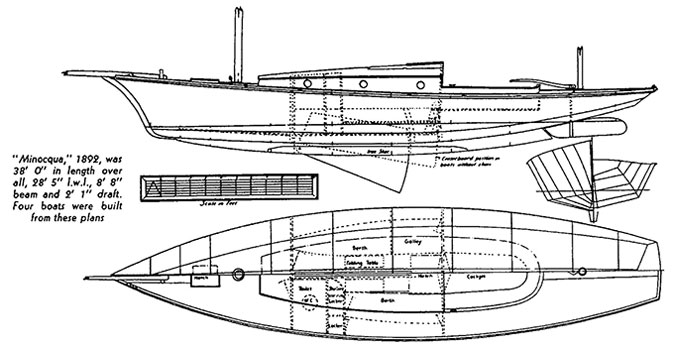

MINOCQUA’s Lines, from The Sharpie Book (originals traced from Clapham by Howard Chapelle)—note the optional outside-ballast keel.

Another innovation employed by Clapham was the addition of an optional full-length, curved keel, which incorporated outside ballast, making the design truly ocean-worthy. In general proportions, however, the new design was consistent with true sharpies in beam-to-length ratio, extreme shoal draft, low freeboard and strongly flared topsides.

Both bottom and topsides planking employed “developable surfaces” (able to be planked from flat panels), allowing planking from standard lumberyard plank stock with no spiling required. In this, Clapham’s hull retained the simplicity of construction and low cost of the true sharpie.

What this means in today’s world of cold-molded wood/epoxy construction is that the hull can be built easily, rapidly, and very inexpensively using full sheets of marine plywood. It can also be easily built in aluminum or steel.

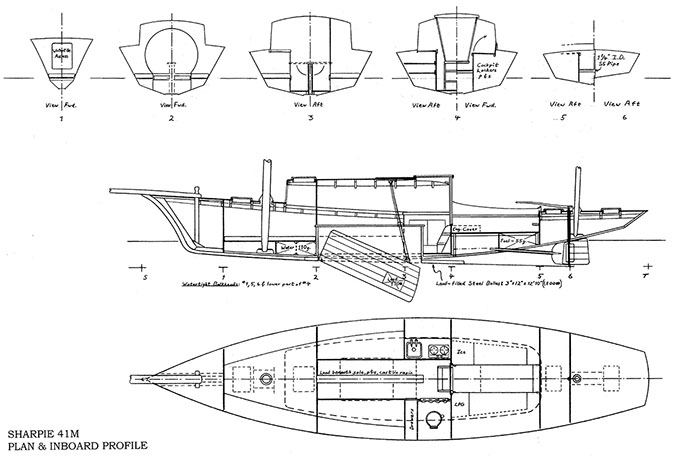

I included MINOCQUA in The Sharpie Book (1994), but didn’t draw building plans for her until a decade later (2004), when I designed my own version for cruising, which I named MINOCQUA II. I designed my version to be built using full sheets of marine plywood over longitudinals and plywood bulkheads. In 2007 I designed a slightly larger model (41 feet) to achieve standing headroom in the cabin. I added a skeg-type hollow box keel, incorporating lead ballast, to make my model self-righting from a full-knockdown (capsize to 95 degrees).

Plan and Inboard-Profile views of my 41′ cruising version of MINOCQUA II.

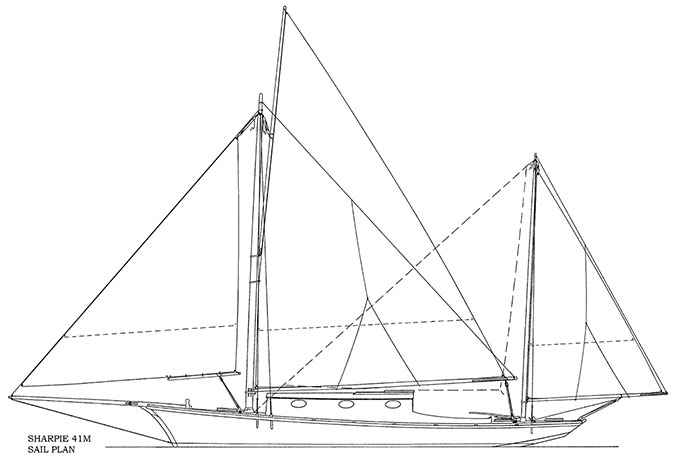

Clapham’s rig is unusual by today’s standards, employing a long, sprung-down plank bowsprit with a big self-tending jib, a “Sliding-Gunter” mains’l, and a yawl Marconi mizzen. I would, however, make one concession to modern thinking, by employing a roller-furling system for the jib.

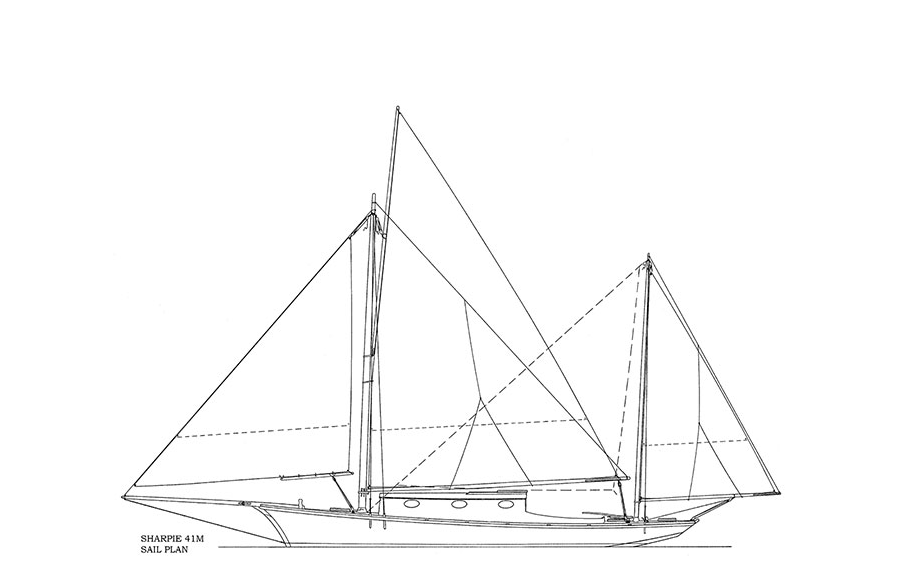

The famous Roslyn Yawl sail plan, on my 41′ cruising version of MINOCQUA II.

Proportions for MINOCQUA II are:

L.O.A.: 40′ 10″

L.W.L.: ;31′ 7″

BEAM: 10′ 0″

DRAFT: 2′ 2″

DISPLACEMENT: 8,750 lbs. (approx.)

BALLAST: 3,250 lbs. (approx.)

SAIL AREA: 750 sq. ft.

TANKAGE: Fuel: 55 gal.: Water: 110 gal.

AUXILIARY POWER: Inboard 2-cyl diesel (15hp) or outboard in an offset well located just aft of station #6

Thomas Clapham was an outspoken champion of shoal-draft yawl-rigged cruisers, and designed numerous additional models, including a 61’er for a member of the New York Yacht Club in 1881. His nonpareil sharpies could be single-handed by lowering the main in strong winds and sailing under “jib and jigger”. His designs had a great reputation for speed, and won many races. They were well-balanced, often steered themselves, and sailed with dry decks in rough weather. His hulls were remarkably stable, and were considered uncapsizable with the optional outside-ballast keels.

In the November 1915 issue of Yachting, William J. Starr wrote:

…flaring topsides and lifting type of overhanging ends gave them much reserve buoyancy and stability in spite of their relatively narrow breadth… In form of section these Clapham sharpies were the V-bottom boats of today—nothing more, nothing less—starting with a sharp V entrance forward (originally used to prevent pounding), with a good amount of straight deadrise amidships, and flattening somewhat aft into a very clean run. The secret of their speed with small driving power and their clean sailing was the perfectly fair segmental rockering of their bottoms from forward to aft, and perhaps fully as important, the perfect diagonal formed by the sweep of their bilge when heeled under sail.

What this technical description means to the layman is that water flowing under this hull, when heeled over, has the minimum possible impediment, and that the immersed planes of hull bottom and topsides are symmetrical, with the chine acting like second keel. Starr further explains that Clapham experimented with towing models, and faired his lines using straight-grained pine battens, to assure that there would be “no concealed humps or hollows to stop the clean run of the water.” Brilliant architecture!

I think Thomas Clapham, right along with Nathanial Greene Herreshoff and Ralph Munroe, must share the title of “Father of the Modern American yacht”.

Appleton, Maine, 10/24/13