Restoring KATIE MACK

A bridge-deck cruiser for the golden years

A bridge-deck cruiser for the golden years

ALISON LANGLEY

KATIE MACK is a 46′ bridge-deck cruiser built in British Columbia and launched in 1932. She was a rumrunner originally. Today, she cruises New England waters as the summer retirement home of Pam and Hugh Harwood.

Alison Langley

KATIE MACK’s pilothouse is light and airy, and it offers all-around visibility. Here, the newly restored yacht is on sea trials soon after her relaunching last autumn.

Sometime around 2010, Hugh and Pam Harwood began thinking vaguely about a path to a new and simpler life of exploration and waterborne travel. In March 2013, things came into focus: at the annual Maine Boatbuilders Show in Portland, Hugh got a “crazy idea” that set the couple on an inexorable track. He had been a family doctor for nearly 25 years, and he would exit his solo practice. Pam would sell the 25-acre alpaca farm that, for more than a decade, had supplied her thriving knitwear business. They would sell their house in Maine and then combine the proceeds from the house, the farm, and the practice to purchase a boat in which to live and cruise the New England coast. It was, it seemed, a tidy blueprint to the life they’d been dreaming of. The multiyear process of getting the boat they wanted, however, turned into a big, rewarding, and unanticipated part of the adventure.

They knew they wanted a wooden boat. Hugh had been smitten with them since he was a young man when, as a financially challenged medical resident, he had discussed with the Maine boatbuilder Ralph Stanley the construction of a 21′ William Fife–inspired cutter. That conversation at first yielded only a half model; it would be 17 years before Hugh could ask Ralph to build the real thing. The cutter project inspired the Harwoods to consider an even more ambitious goal—and the idea of living aboard during retirement. Hugh and Pam studied various types of boats over the years, and ultimately homed in on a very specific style of powerboat.

They wanted a light, airy pilothouse, a true cook’s galley, and an ample stateroom with a comfortable berth. They wanted space to lounge and, as sailors, wished to move at just a modest clip while they spoke in conversational tones. And they wanted these amenities to be wrapped up in a vintage aesthetic—but an authentic one, not a caricature. They looked at candidate boats from Maine to Annapolis, in a process akin to Goldilocks searching Yachtworld: this William Hand motorsailer, with its 72,000 lbs of displacement, was too big; that vintage Elco, with its leaded glass and velveteen cushions, was too precious. And then they found KATIE MACK, a 46-footer with a deck-level pilothouse set amidships—a so-called bridge-deck cruiser. She was just right in terms of looks, layout, size, and style. Being 80 years old and fastened with iron, she had some suspected structural issues, and she was 3,000 miles away, in Tacoma, Washington. But those were obstacles that could be addressed.

Puget Sound Maritime Museum

Wesley McDonald owned KATIE MACK (then called MARBOB) when this photograph was taken in 1949. In July that year, he raced her from Olympia, Washington, to Nanaimo, B.C., in an event called the Capital to Capital International Cruisers Race.

There’s an old saw in the real-estate business that declares the three most important considerations in purchasing a property to be location, location, and location. The point of it is that there are some things one can change about a property, and some—location being the most intractable—with which one is stuck. The old saw might be bent a little bit in the case of the Harwoods and their boat purchase. They knew what they wanted, and they knew what could be changed in a boat—and what couldn’t. KATIE MACK’s vintage, unspoiled pilothouse offered a 360-degree view of the boat’s surroundings. It had a sublime patina—the kind gained only through decades of continuous use and care. There were two ample staterooms and a head in the after portion of the accommodation, and a tidy galley space forward. She was maintained, but apparently weakened from age. The stateroom and galley spaces had been well cared for by her shipwright owner, but they needed overhauling to suit the Harwoods’ requirements. The pilothouse was perfect in terms of both looks and function.

They did a little more looking, but KATIE MACK became the standard by which they came to judge all other candidates—none of which measured up: “Nice,” they would think, “but not as nice as KATIE MACK.” They purchased her in 2013, loaded her onto a trailer, and had her shipped east to Maine. There, they would spend a season cruising in her and then have her surveyed in order to plan a refit. That first season of cruising only deepened their appreciation for KATIE MACK, which turned out to be a very good result, given the survey report they were about to receive.

The brothers John D. and William L. McGregor built KATIE MACK in Vancouver, British Columbia, and launched her in 1932. They weren’t boatbuilders by trade, but they had transferable skills: one was a machinist, and the other an engineer. They christened her HOALOHA, which means “cherished friend” in Hawaiian, and she was to be engaged in the lucrative international transport of fine Canadian whisky to U.S. ports, satisfying the demand brought on by Prohibition. As such, she was built without the distinguished-looking pilothouse that now defines her character.

Six River Marine

Upon survey after her arrival in Maine, KATIE MACK’s hull was found to be extensively deteriorated and in need of rebuilding. The ensuing job was a careful balance of keeping her shape, fitting new wood, and cutting away old structure.

Six River Marine

The new hull planking is Alaska yellow cedar, chosen because it came from Vancouver, where KATIE MACK was built.

The identity of the designer is vague. Ted Geary, the great West Coast naval architect, appears on some of her paperwork, and one former owner attributes the design to him. But without clear confirmation of this, Hugh prefers to say that her designer is unknown. She was launched with a then-eight-year-old 85-hp Sterling gasoline engine. Pam reckons that the brothers earned about $800 per day ferrying whisky to the United States, but this profession was short-lived: The Volstead Act—the legislation prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the United States—was repealed in 1933, and along with it went the demand for the services of rumrunners.

Six River Marine

KATIE MACK’s hull was rebuilt without disturbing the pilothouse. That structure remains as it was built, and it has a glowing patina that could not be replicated in a replacement.

A Canadian mining engineer named Wilson Gouge and his wife, Winnifred, purchased the yacht in 1936. A year later, they hired the Canadian division of Boeing Aircraft Corporation to refit her (the company had recently purchased a shipyard in Vancouver) for comfortable cruising. They added the pilothouse. A few years later, in 1940, the Gouges had the boat repowered with a 165-hp Lycoming, an aircraft engine, whose transmission control was pneumatic. The air tank for this system, which is still in place, is purported to have come from a B-25 bomber—the first of which were then being built by Boeing.

A handwritten notation on the yacht’s registration indicates that she was “sold to foreigners,” in 1943, and another reads “Registry Closed.” The foreigner was Wesley McDonald, owner of the Avalon Theater in Olympia, Washington. He changed her name to MARBOB, and cruised her as far as Alaska, sometimes for months on end. In 1951, he repowered her with the Graymarine 6–71 that is still in the boat. McDonald kept MARBOB for more than four decades and sold her in 1987 to Christopher and Susan Colby, who named her WILD ROSE and lived aboard in Newport Beach, California. They rebuilt the old Graymarine diesel in 1992.

After a brief stint as a program boat for a Christian youth organization in British Columbia in 1993 and 1994, the boat went to Michael and Cheryl Baher, who also lived aboard. Her next owners, Jack McCarley and Jill McJury, lived aboard, too, in Tacoma, after purchasing her at a foreclosure auction in 2004. They named her KATIE MACK, after both of their mothers. McCarley is a trained boatwright, and he did much to upgrade the structure, systems, and accommodation. Eventually, however, KATIE MACK was in need of a thorough overhaul. She was fastened originally with clenched iron nails—an expeditious and economical process in terms of materials and labor. But over time the iron had degraded, and so had the wood around it. That’s the condition the Harwoods found her in: wonderfully kept, but with the inevitable structural needs brought on by age and iron. They wouldn’t know quite how bad it was, however, until the end of the 2013 season.

Alison Langley

The galley includes a solid-fuel stove, a propane-fired single burner for the kettle, and ample stowage and counter space.

Alison Langley

The main saloon, which is aft of the galley, has two generous settees. It is situated just forward of the pilothouse.

Alison Langley

The master stateroom is all the way aft, at the end of a passageway that also leads from the pilothouse to a second stateroom and the head.

When the Harwoods hauled KATIE MACK for survey in the fall of 2013, they stripped her entire bottom to give the surveyor, Paul Haley, a better look. Haley summarily condemned the bottom. Some of the planks were so punky that a finger could be poked right through them. The original clench nails were mostly still holding but had, by necessity, been backed up by additional fastenings over the years. Chip Miller is co-proprietor of Six River Marine in North Yarmouth, Maine—the yard the Harwoods would hire to rebuild KATIE MACK. He recalls the fastening situation: “She had some of everything in there.” His business partner, Scott Conrad, says that they tried to remove fastenings for the survey, but that it was impossible to do so. In one plank-to-frame joint, they counted no fewer than 13 fastenings. KATIE MACK needed a new hull. Hugh recalls that after the survey, he and Pam went home for the weekend, came back, and said, “Let’s keep going.”

The Harwoods chose Six River after putting the job out to bid and receiving an attractive quote from Chip and Scott. Their project history (see sidebar), proximity to the Harwoods’ home, and references sealed the deal. “One fellow,” Hugh told me, “remarked he had so much fun [with his project with Six River] he was looking for another boat to do it again someday.”

The yacht would occupy Six River Marine’s 15,000-sq-ft facility for the next four years. “There were actually two 46′ boats in the shop,” says Chip of the period of KATIE MACK’s restoration. “One of them left in a dumpster.” The other one emerged from the shop last autumn with a brand-new hull, but retaining the glowing patina of an 80-year-old boat. That’s the signature element of this particular job: KATIE MACK has the strength of a new boat, but she carries the priceless record of her long life. The result is breathtaking and the process was fun—“the most fun thing I have ever done,” Hugh says.

The hull-rebuild strategy is a study in economy. The restoration of a plank-on-frame hull is often viewed as a painstaking process of fastening removal and replacement and careful fitting of old wood to new. That wasn’t the case with KATIE MACK, in which the job proceeded more as if building a new boat by using the old one as the construction jig. The shape of her hull was more-or-less intact, but the stuff it was made of—the fastenings, the frames, the planks, and a portion of the keel—was in rough shape. That freed the builders from a curatorial excavation of some material and the saving of other and allowed them to build a new hull while leaving the cabin, deck, and engine in place.

Alison Langley

With the help of Six River Marine, Hugh and Pam Harwood spent four years bringing their dream of a floating home to fruition.

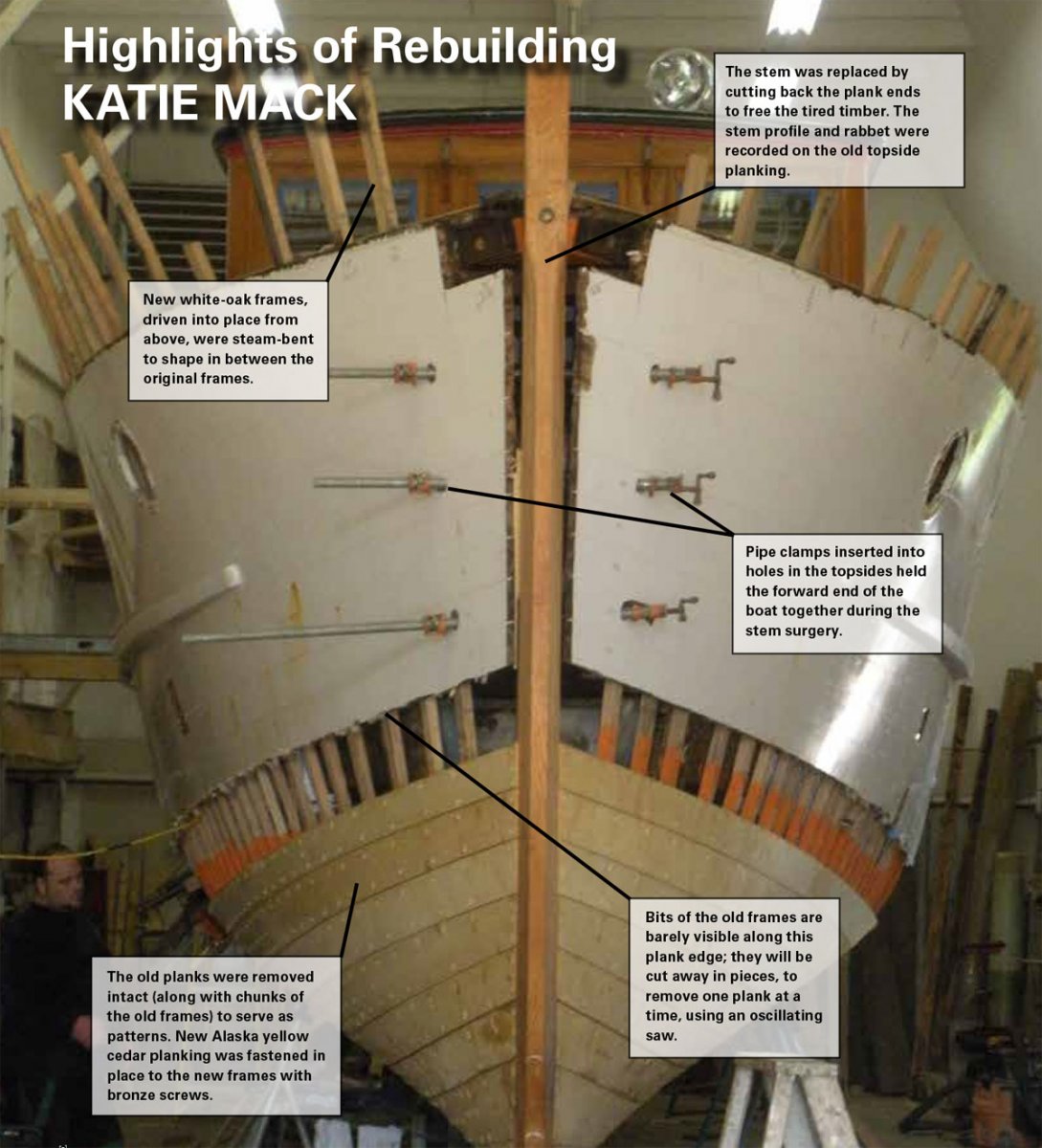

The job began with reframing, which typically requires that the old frames be removed, either wholesale or in chunks, and that new ones be bent into their positions. That’s what one does if precious planking is to be preserved. But the Six River builders didn’t have that constraint with KATIE MACK, because all of the planking was to be replaced once reframing was complete. So, they took a different tack: After opening up the deck edge and clearing the interior of any obstructing joinery, they bent new frames into new positions between the old ones. Roughly 80 percent of the new frames were kerfed—that is, a saw cut was run along their lengths to rip them into two laminates so they’d bend more easily. The builders steamed the new oak frames for the requisite amount of time (an hour per inch is the age-old guide to steaming oak), and drove them into place from above. They also scarfed on a new section of the Douglas-fir keel, and replaced the stem, horn timber, and transom.

Various clamping strategies held these new frames in place. These included bridging the space between original frames with temporary timbers to create clamping pressure on the new frames. The builders bored holes in the planking at the stem to provide access for bar clamps.

When the reframing was complete, things got interesting. The old frames were holding the boat together, so they couldn’t be removed all at once or the boat would fall apart. So, Chip and Scott removed the planks one by one with the aid of an oscillating saw plunged into the plank seams to cut the original frames. Each plank thus came off the boat with a short section of frame attached to it, and the remainder of the frame still in its original place, cleating the planking together. Temporary ribbands on the outside of the boat helped to keep things fair. The builders created a three-plank-width window in this manner, and then removed and replaced one plank at a time. They never removed a single fastening during the entire job. “If there had been a time-lapse movie of the process,” Chip says, “we’d see the old boat melt away and the new boat grow in its place.” The new planking is Alaska yellow cedar, which Hugh chose because the source was in Vancouver, where KATIE MACK was built.

Alison Langley

KATIE MACK is a bridge-deck cruiser, which means that her pilothouse sits amidships, at deck level, and opens into below-deck living spaces forward and aft.

The Harwoods were very involved in the work. While Six River Marine did the heavy lifting on the structural and technical portions of the job, Hugh and Pam tended to the finishwork in the galley, staterooms, and head. Systems were upgraded; the boat was thoroughly rewired; the galley was rebuilt and its fixtures overhauled. Vintage bronze hardware was carefully collected and installed. But that magnificent pilothouse remained untouched.

“This pilothouse is what sold it for me,...” Pam said as we cruised down the Royal River on a crisp day in early November last year. KATIE MACK had been moored off Yankee Marina in Yarmouth since her launching just a few weeks before, and the Harwoods had invited me along for a day trip, along with Chip and Scott. They were fine-tuning the boat’s systems before laying her up for the winter in Maine before the Harwoods moved to Martha’s Vineyard, where Hugh had a taken a seasonal job in a hospital. Pam continued, “…that seat right there.” Although she has sold the alpaca farm, she is still an avid knitter and still maintains a woolens business, and the sprawling settee that spans half the width of the pilothouse is an idyllic place to sit and read, knit, or watch the world go by.

Alison Langley

KATIE MACK’s expansive foredeck looks much as it did in the 1940s. Aside from repairing the deck edge, which was opened up for hull framing, it required little work.

We were speaking at a civil volume as the brown-mud banks of the river gave way to the rocky islands of Casco Bay. “You couldn’t have a conversation in the pilothouse before,” Hugh says of the boat’s former lack of soundproofing. He has not assessed the boat’s performance since the rebuilding, but she has the same engine, the same hull shape, and essentially the same 32,500-lb displacement as the boat Hugh and Pam purchased, so the pre-restoration numbers likely tell the story: the unrestored KATIE MACK cruised at 8 knots at 1,250 rpm, while burning three gallons of diesel per hour. She topped out at 11.2 knots wide open, and burned a heck of a lot more fuel at that speed. Hugh and Pam had shown me around the boat before we set out on our one-hour tour. A short ladder leads forward from the pilothouse into a saloon with settees on either side, and this leads to the far-forward galley, whose lockers are painted in Kirby Paint Company’s “sand” tone—a light cream color. The bright-finished iroko countertops are finished in a food-grade combination of citrus oil and tung oil. A Shipmate solid-fuel stove warms the space and serves for cooking large meals, and there’s a single propane-fired burner for the kettle and small, quick meals.

Another ladder leads from the pilothouse aft to a passageway, and off this passageway are a head, a utility space, and the master stateroom. It’s a perfect setup for a couple. The utility space was once a second stateroom, but this has been given over to such liveaboard necessities as a washer-dryer, wifi gear, a folding bike, a workbench, and a 12-volt freezer. The head has a corner sink, a shower, and a massive teak grate which, the Harwoods told me, came from a hatch of a Canadian minesweeper. It was too big to be brought aboard, and would not have become a part of KATIE MACK had the transom not been removed for rebuilding. The resulting gaping hole in the stern allowed the massive teak grate to pass into the accommodation in one piece before the new transom was installed. A big bronze steaming light, repurposed as a wall sconce, lights the head. Such details abound in KATIE MACK: Under the aft ladder is a red courtesy light—a former port-side running light from a larger vessel.

The master stateroom, which is all the way aft, is a cocoon of white paint accented in aquamarine and bright trim, with just enough stowage and a full-size bed. Wood-trimmed fans ventilate the space, and a companionway with hinged doors leads to the afterdeck—and a view of whatever slice of paradise the boat is cruising at the moment.

It has often been said that all boats are a compromise: some trade speed for comfort; some trade comfort for good looks. KATIE MACK does not feel like a compromise. Rather, she feels like an expression of deep cooperation—between owners and builders, and between a husband and wife. This point was driven home for me when, on our mini cruise, Pam was telling me about her alpaca farm. “That’s my thing,” she said. “Medicine is Hugh’s thing. This boat is our thing.”

Matthew P. Murphy is editor of WoodenBoat.

Six River Marine

Chip Miller and Scott Conrad are the principals in Six River Marine, a 15,000-sq-ft boatbuilding shop in North Yarmouth, Maine. Chip grew up in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and Scott in New York and Los Angeles—but met in the early 1980s in Alaska, where they both worked in a salmon cannery.

Linda Thurston

Scott Conrad (left) and Chip Miller met during their college years; they have been business partners in Six River Marine for almost three decades.

Their paths diverged and then came back together in the ensuing years. Chip moved to Maine, where he studied boatbuilding at the Apprenticeshop in 1986–87, when it was housed at the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath. After completing his apprenticeship, he went to work at Dion’s Yacht Yard in Salem, Massachusetts. In the meantime, Scott graduated from Humboldt State University in Arcata, California, and then moved back East to a career in construction engineering, building such necessities as foundations and roads. That lasted only a year. “It wasn’t a great fit for me,” said Scott. “I wanted to learn woodworking.” For the subsequent four years, he labored in various furniture shops around the Boston area.

In the meantime, Scott and Chip had reconnected, and they shared a budding entrepreneurial streak. They each had young families, and purchased a two-family home in Somerville, Massachusetts, that served as their combined residence for two years and as a rental property for several years after that. Chip moved back to Maine around 1989 to pursue a new boatbuilding opportunity with the lobsterboat builder Peter Kass in South Bristol (see WB No. 227) and then with H&H Boatworks in Phippsburg, Maine. Scott moved to Maine in 1993 and continued working in furniture shops for four more years.

While working their day jobs, the future business partners were honing their skills and developing a portfolio of side jobs involving boats and furniture.

Alison Langley

Six River Marine made its reputation early building boats styled after Alton Wallace’s pioneering center-console skiff, the West Pointer.

“The boat stuff was taking off faster than the cabinetmaking,” said Scott. The part-time boat work became full-time in 1995. For one of their early restoration jobs, a 1928, 36′ Lawley-built cruiser called CHATAUQUA, they conducted the work in the space of a former drywall factory in South Portland, Maine. That project was accomplished in installments over several years while the owners used the boat seasonally. CHATAUQUA won various accolades at boat shows in the late 1990s, and cemented the partners’ reputation. They bought and refurbished their shop, a former barn, in North Yarmouth in 1997, incorporated as Six River Marine, and never looked back.

Their gallery of completed restoration projects includes a number of fine powerboats and sailboats, including a 36′ Ted Hood–designed yawl whose bottom they rebuilt, another bottom rebuild of a 33′ Knutsen sloop, and new laid decks for a 35′ Vinny Cavanaugh bassboat. They also made a reputation building new boats based on Alton Wallace’s classic West Pointer design, a center-console, round-bottomed skiff available in either 18′ or 22′ lengths. With Alton’s blessing, Chip designed the 18-footer in the time-honored tradition of carving a half model and then lofting its lines full-sized; he designed the 21-footer on paper. In the boom years of the early 2000s, Six River had eight employees. Now it’s just Chip and Scott—and a couple of independent boatbuilders as needed.

The bridge-deck cruiser KATIE MACK left the Six River Marine shop in early winter last year. At the time of this writing, Chip and Scott are lofting a 17′ skiff of their own design for a customer who wanted a boat like their West Pointer—but a little bit smaller. Chip once again carved a model to design that boat.

—MPM

Six River Marine