MADDY SUE

Restoration of an iconic Maine picnic boat

Restoration of an iconic Maine picnic boat

BENJAMIN MENDLOWITZ

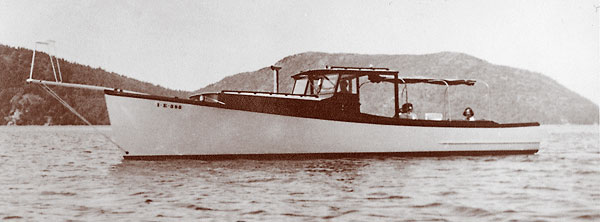

After a thorough restoration at Darling’s Boatworks in Charlotte, Vermont, MADDY SUE’s home port is on Lake Champlain, but she returned to Maine waters for a time in the summer of 2013. Built by Chester Clement on Mount Desert Island in 1932 for lobstering and fishing, she was influential in the development of the type of pleasure boats much loved by the island’s summer population.

Reading about the picnic boat MADDY SUE on this magazine’s “Save a Classic” page in 2011 brought back vivid memories for Jan Rozendaal. In his youth, he had seen such boats during family cruises to Mount Desert Island, Maine. To him, the boat’s appeal was untarnished by her 80 years of age or the fact that she had been sitting in a boathouse for the past 15 of those years. He bought her knowing that she would need a complete restoration. He also understood what that meant: His previous acquisition of the 1902 Buzzards Bay 30 MASHNEE, also found through “Save a Classic,” turned into a three-year project at Darling’s Boatworks in Charlotte, Vermont.

SOUTHWEST HARBOR PUBLIC LIBRARY

Under first owner Francis Spurling, MADDY SUE, then called TRAILAWAY, had a long bow pulpit for harpooning tuna. She also had a roll-up canvas awning over the cockpit, and a stovepipe suggests a source of cabin heat.

Rozendaal’s passion for wooden boats dates back to days when his father, a physician for General Electric Corp., used to drive the family to Mystic, Connecticut, for weekend sailing on Long Island Sound or to set out for summer vacation sails to the Maine coast. Since then, Rozendaal has had a succession of wooden boats, which in recent years have been restored and maintained by George Darling, proprietor of Darling’s Boatworks. “It didn’t matter if Jan and his siblings were seasick or wanted to do something else,” Darling says, “Jan’s father was going to go sailing, and there were no choices for the family other than sailing.” The motoryachts Rozendaal saw in Maine were descendants of lobsterboats, and he was not alone in most admiring the boats built by Raymond Bunker and Ralph Ellis (see WB No. 215), especially JERICHO (see photo, page 47), a 42-footer built in 1957 for Thomas S. Gates, Jr., who later became U.S. Secretary of Defense.

TODD A. CROTEAU/NPS

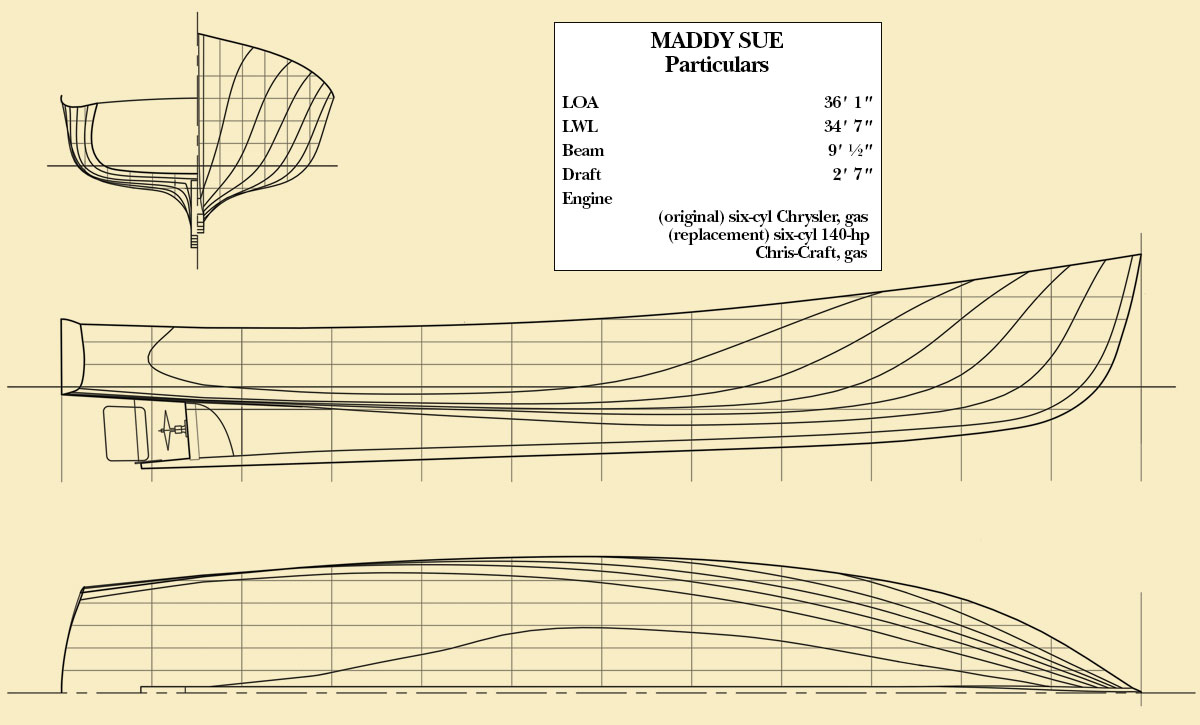

MADDY SUE’s hull lines were recorded by Todd Croteau of the National Park Service’s Historic American Engineering Record after the boat was declared a historically significant boat type.

After Rozendaal bought MADDY SUE in late 2011, he had the boat trucked from Cranberry Island Boatyard, which is on an island lying just off the south end of Mount Desert Island, to Darling’s. As the boat came off the ferry at Southwest Harbor, she caught the eye of Kathe Newman Walton, who runs the Newman Marine brokerage there with her father, Jarvis Newman, who was one of the first to build Friendship sloops and lobsterboats in fiberglass. “MADDY SUE passed right by my office,” she remembered. “Everyone knew she was out on Great Cranberry Island and for sale, but no one had managed to buy her.” In a subsequent email correspondence with Rozendaal, she learned of his admiration for Bunker & Ellis boats, and he was delighted in turn to learn that Walton is Raymond Bunker’s granddaughter. Rozendaal may not have gotten a Bunker & Ellis, but in MADDY SUE he arguably got the boat that opened the way for boats like JERICHO.

COURTESY OF WILLIE GRANSTON

A 1951 built-down lobsterboat launched by Bunker & Ellis on Mount Desert Island nearly 20 years after Chester Clement built MADDY SUE clearly shows the influence Clement had on his successors during the early years of picnic boat development. The boat was named JERICHO, the same name given to a later Bunker & Ellis that shows significant modification of the type (see photo below).

MAYNARD BRAY

MADDY SUE rested in the same spot at Cranberry Island Boatyard for more than 15 years, awaiting an owner willing to undertake a full restoration.

Dr. Richard Lunt studied lobsterboats for his 1976 doctoral thesis in folklore at Indiana University. His interest was personal, since his family had lived in Maine for generations and he had grown up at the head of Somes Sound on Mount Desert Island. Sensing that the era of wooden lobsterboats was coming to an end, he interviewed dozens of boatbuilders, men completely steeped in the craft. Raymond Bunker and Ralph Ellis were among them, and so was Ralph Stanley (see WB No. 164), who started building boats in 1946. “Ron Rich was still shaping the backbone of his boats with an adze in 1970,” he recalled of another builder. “He just had that kind of skill and ability, and he could do perfect work with that adze while talking to you.”

Two distinct lobsterboat types developed in Downeast Maine, one centered on Jonesport and the other on Mount Desert Island. The early Jonesport boats sprang from peapods and other local double-enders. Then, in 1912, Wilton Frost, an immigrant from Digby, Nova Scotia, began building torpedo-sterned boats that caught on quickly. They had flat floors and a deep skeg bored for the propeller shaft. The earliest ones had “washtub” transoms, referring to their vertical staving.

Frost’s boats were synonymous with speed, something that Jonesporters still prize today. With its simplified construction, the skeg-built style was light, and the flat run of the hull aft contributed to speed. After World War I, a new transom-style boat emerged—appropriately known at the time as “cut-off sterns”—but their aft tumblehome remained, a vestigial memory of their tub-sterned predecessors.

In the Mount Desert region, double-ended “pumpkinseed” or “melonseed” hulls, along with Friendship sloops, were the primary lobsterboat types used before marine engines came into widespread use. In the 1920s, boatshops on the island were established by Chester Clement in Southwest Harbor and Cliff Rich in Bernard, and one or the other was the first to inaugurate square-sterned lobsterboats, which became the dominant style in the area. As Lunt discovered, almost every boatbuilder on the island got his start working for one of these two men. Bunker came of age working for Clement and managed the shop after his mentor died in 1937, and later he went into partnership with Ellis.

MAYNARD BRAY

Her original power was a modified six-cylinder Chrysler truck engine from the 1960s, which was replaced by a rebuilt Chris-Craft.

The Mount Desert boats differed from their Jonesport cousins primarily by having what is known as a planked-down keel, a type of construction also known as built-down or semi-built-down, which considerably strengthened the keel. Mount Desert boats are more heavily built and have greater displacement than their Jonesport counterparts. A Jonesport builder would be quick to point out that this made them slower, but a Mount Desert builder would reply that Jonesport boats were flimsier and their builder’s obsession with speed short-sighted.

Mount Desert designs also felt the powerful influence of the island’s summer population, which didn’t exist in Jonesport or across Moosebec Reach at Beals Island, where builders built similar types of lobsterboats. As early as the 1890s, Mount Desert fishermen were cleaning up their Friendship sloops during the summer to carry passengers, beginning a trend of fishing during the winter and running charters for people “from away” during the summer. During the years before World War II, the picnic boat slowly emerged as a type, distinct from the working lobsterboat.

The patterns of working life changed for boatbuilders as well as fishermen. Almost all the boatbuilders that Lunt interviewed, including Bunker, built boats only in winter, leaving their summers free to captain boats owned by people from away.

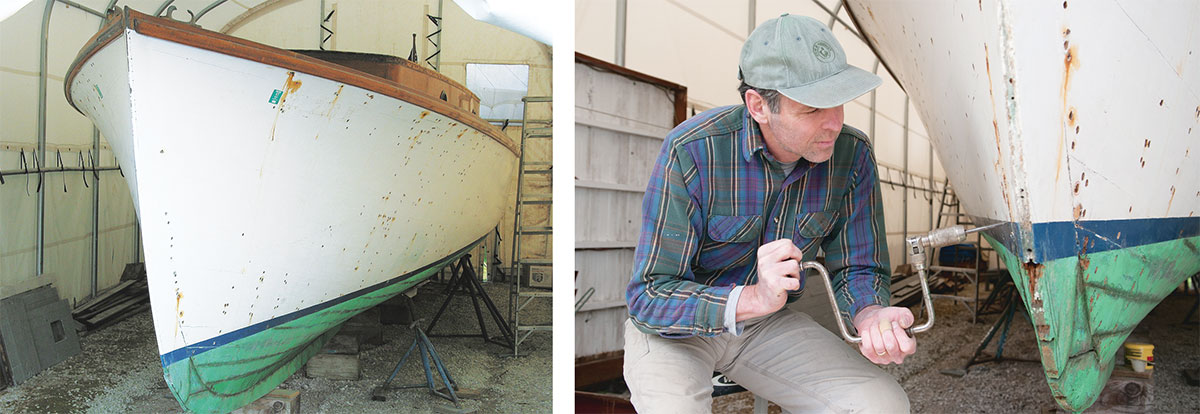

DOUGLAS BROOKS (left), LARRY ASAM PHOTOGRAPHY (right)

Left—Before restoration, rust streaks revealed the degradation of her original steel fastenings. Some of the screws had rusted completely away, and a refastening had crowded the hull with screws and nails. Right—The author removes fastenings; the hull was refastened with silicon-bronze screws.

Capt. Francis Spurling commissioned Chester Clement to build him a 36′ boat in 1932. Spurling christened her TRAILAWAY, and he used her for fishing and lobstering during the winters and chartered her for summer use. TRAILAWAY was launched without a deckhouse, but within a decade a mahogany cabin was added, along with a steering shelter, replacing the peaked canvas sprayhoods that fishermen first rigged as cockpit shelters. A subsequent owner rechristened the boat MADDY SUE after his wife, Madelaine, and daughter, Susan. MADDY SUE by then was used purely for pleasure, shaping the very idea of what a picnic boat should look like.

While researching the photograph archives at the Southwest Harbor Public Library, I met Willie Granston, a former curator of the Great Harbor Maritime Museum in Northeast Harbor, who showed me a small color photograph of a picnic boat (see photo above). At first I was sure it was MADDY SUE. It had the same subtle sheer, and the house and steering station looked the same. It even had the pipe stanchions and canvas cockpit awning that I had seen in old photos of MADDY SUE. Granston smiled and corrected me. “This boat,” he said, “was built by Raymond Bunker in 1951,” almost 20 years after MADDY SUE’s launching. Except for the canted-forward face of the house, which I hadn’t noticed at first, she could have been the same boat.

MAYNARD BRAY

MADDY SUE left Great Cranberry Island for the first time in many years via a boat trailer bound for Darling’s Boatworks in Charlotte, Vermont.

This says a lot about the influence that Clement’s work exerted on his most famous apprentice. Later, Granston wrote me, “Clement came up with the idea of the lobster yacht, but Bunker & Ellis made it big. Raymond Bunker and Ralph Ellis went into business in 1946 and built 58 boats between 1946 and 1978, working only in winter. These boats were the Packards of the ocean, and were the boat to have. The earliest ones were much like MADDY SUE. By the 1950s and ’60s, however, they were really at their prime, turning out boats like JERICHO [see inset below].”

The automotive reference is appropriate because the styling of the later Bunker & Ellis cabins is perhaps their most eye-catching feature. Bunker must have been looking at the fine cars of the summer crowd, imagining how he could incorporate the best qualities of streamlined design. With the reference to Packards, Granston slightly missed the “marque”; Stanley told me that Bunker’s windscreen was inspired by the late-1930s Lincoln Zephyr.

Above the sheer is where Bunker separated himself from his mentor. The subtle S-curve of the after edge of JERICHO’s windscreen fairs into a tapered coaming, that trails the curve to the stern. It’s a segue that relieves the horizontal lines of the cabintop and overhead, and the angles of the forward face of the cabin and windscreen. JERICHO’s looks flirt with motion while at rest.

Below the sheer, it’s hard to imagine improving on Clement. MADDY SUE has strong flare forward, and her sheer curves very gently to a point about two-thirds of the way aft, where it begins to crown the tumblehome at the stern. I was told that none of the other Mount Desert builders curved their transoms as much as Clement. It’s pure style over function, which obviously didn’t bother Clement.

DOUGLAS BROOKS (both)

Above left—With original transom planking removed, the deterioration in its framing was evident. Above right—The replacement transom, made up of three layers of 6mm plywood and an exterior mahogany veneer, was laminated over a curved form before installation.

I joined MADDY SUE’s restoration in 2012, for wood repair and fabrication, including reframing and refastening the hull, rebuilding the cockpit sole, and building a new transom. Later, Peter Russett, the senior employee at Darling’s, took the lead in fiberglassing the decks and cabintop, painting, engine installation, and final assembly. Darling himself oversaw the restoration, in consultation with Rozendaal.

At first glance, MADDY SUE looked fairly solid, but upon closer inspection she revealed her share of problems. The hulls of these boats have hard bilges with a sharp reverse curve near the keel (known locally as the tuck), and to get the tight bends that the frames require, the builders would kerf the white oak frames before steam-bending them. The cedar planking was fastened to the frames with galvanized clench nails. Clement’s designs are recognizable for their very tight tuck.

Not long after I started working on the boat, I talked to Steven Spurling, MADDY SUE’s second owner. The son of the boat’s first owner, he was 92 at the time. Along with Stanley, then 83, these two men are the last of the old generation of Southwest Harbor boatbuilders. I sent photos of the restoration to Spurling in the weeks before I met him, and his first words to me registered his disdain for replacing MADDY SUE’s planked oak transom with laminated plywood and mahogany veneer. He then crossed his arms and, with what might have been a smile on his craggy face, asked, “And how many of her frames are broken in the bilge?”

In addition to being a professional captain, Spurling worked for several boatbuilders in Southwest Harbor. Even today, he still builds skiffs, including a lovely lapstrake design that an ancestor, Wesley Bracy, built on Great Cranberry Island. He was taciturn until I asked him about Clement, and then his answers became loud and insistent: Clement was the best. He told me how Clement had once repaired a schooner right on the shore of Great Cranberry Island where it had gone aground. He had also built rumrunners, some as long as 80′. He talked about Clement with such familiarity that I assumed they had known each other. But Clement died in an auto accident in 1937, when Spurling would have been a teenager. As Lunt points out, coastal Maine was made up of isolated and tight-knit communities, so Clement’s legend would have been remembered by many and deeply woven into the fabric of the place. The builder may be gone, but the boats he built keep his legend alive.

Today, MADDY SUE is, at first glance, all lustrous varnish and gleaming paint. It is easy to forget that she was built at the height of the Great Depression and marks a transition from workboat to pleasure yacht. Her lines are unquestionably gorgeous, but her construction details betray time and cost pressures. For example, to check the level of the cockpit sole beams I was replacing, I started using the cockpit coaming as a reference but discovered that the height in relation to the original beams differed from one side of the boat to the other by almost an inch. Darling suggested I check the engine bedlogs, the companionway threshold, and any other original athwartship timbers. They all varied slightly. I finally used a transit to establish the waterline amidships, but with the boat leveled to her waterline the stem was out of plumb and her sheer and coamings were not at the same height side-to-side.

Later, I asked Ralph Stanley about this. “Remember,” he said with a laugh, “these boats were built in a hurry!” He told me of a 38-footer that Clement built in just 21 days for a customer named Harvard Beal. “He put just four floor timbers under the engine and then only a few more fore and aft. The customer took her out and gave her a pounding, and the nails came right through the planks.” Stanley’s father later acquired the boat and added more floor timbers. “She would still push the plugs off the nails in the floors,” he remembered, “so my father nailed lath over the plugs to hold them in.”

W.H. BALLARD/SOUTHWEST HARBOR PUBLIC LIBRARY, Benjamin Mendlowitz (inset)

In this photograph from April 20, 1938, Raymond Bunker is shown at work in the Hinckley yard on the cruiser PATSY S. Note the kerfed frames visible in the aft section of the hull. Inset—By the mid-1950s, Bunker & Ellis had further adapted the picnic boat type for power cruisers such as JERICHO of 1957. Still in use today, she was among the boats that caught the eye of MADDY SUE’s owner when his visited Maine as a youth.

Early in his career, Stanley himself followed the usual seasonal pattern, building boats during winter and captaining during the summer. “We all worked fast. When I worked up in the shop, the ground would heave [due to frost] and spoil the setup.” Also, Southwest Harbor builders tended to plank from garboard to sheer, instead of first installing a pair of sheer planks and planking to them. “You’d get out a pair of planks per side and work to the sheer,” Stanley said. “An error might creep in as you went, and you’d have to check and trim the sheer.” Then he added, with a smile, “Or, maybe you wouldn’t.”

“When I rebuilt DICTATOR, a Friendship sloop,” Stanley continued, “I put a string down the middle, and she was an inch and a half wider on one side. It didn’t seem to hurt her. A fishing boat was going to be used rough, so people didn’t care and you couldn’t tell.”

This type of construction was fast and solid, but MADDY SUE had spent her entire life in salt water, and her galvanized steel nails had begun to rust. When I first saw her, she had rust streaks across her white topsides. At some point the boat had been refastened with screws of the same material. Below the waterline, these newer screws were actually in worse shape than her original nails. The old boatbuilders talked about using a type of nail with something called Swedish galvanizing, a thicker-than-usual coating that could withstand being clenched without flaking off. MADDY SUE’s original nails looked to be in good shape and were actually impossible to pull.

We began by doing some refastening below the waterline using bronze screws, following some recent repairwork in which her garboards had been refastened. We paid particular attention to the stem rabbet, where plank repair was required and a few hood ends were coming loose. In the topsides, we removed the bungs covering her rusting nails and screws, cleaned out the rust with a small wire brush chucked in a drill, coated the heads with an automotive paint, and plugged the holes with thickened epoxy to seal the original fastenings from moisture and prevent future rusting.

DOUGLAS BROOKS (both)

Left—Deterioration in existing frames called for a significant reframing. Right—Before being steam-bent, replacement white oak frames were kerfed, as visible in the new frames shown in this photo, to prevent breakage.

The original transom’s steam-bent oak planks were not themselves rotten, but some of the framing was, and so was the covering board. In keeping with the owner’s wish for a varnished mahogany transom, a vacuum-bagged lamination of three layers of 6mm marine plywood and a ¼″ mahogany veneer was installed over new framing.

Rozendaal, who frequently visited the project, often stood quietly on the staging gazing at MADDY SUE’s decking of narrow cedar strips sprung to the curve of the sheer. He loved the look, but Darling reminded him that rainwater leaking through the deck had created most of MADDY SUE’s problems, particularly aft, where standing fresh water caused rot to develop in a number of her frames. I made patterns of these frames and laminated replacements out of steam-bent layers of locust. Making them off the boat allowed us to avoid removing the covering boards, which would have been necessary had they been bent in place.

How to treat the deck and cabintops became the biggest question of the restoration. In the end, MADDY SUE was given the same type of deck that Darling’s crew had given Rozendaal’s N.G. Herreshoff–designed MASHNEE: marine plywood sheathed with epoxy and painted with Awlgrip and nonskid. Because MADDY SUE’s deckbeams were sound, we decided to leave her cedar deck in place, first grinding all the paint off and refastening it with stainless-steel ring nails. We covered the planking with a layer of 6mm marine plywood thoroughly bedded in thickened epoxy, followed by an overlay of two layers of fiberglass cloth set in epoxy. Although this did not match the traditional look Rozendaal was hoping for, MADDY SUE now has a long-lasting and completely leak-proof deck and cabintop.

In restoring the cabin, windshield, and steering station, every effort was made to save original material. This meant replacing various parts with new mahogany, which Pam Darling, George’s wife, stained with water-based stain to blend the new and old material before sealing and varnishing. Most of the old hardware and instrument panel were saved and reused. Rozendaal requested two new bronze portholes for the forward face of the trunk cabin and a mahogany bench for the steering station. A new aft bench for passengers, which spans the width of the cockpit, is based on one I saw in a model of MADDY SUE on display at the maritime museum in Northeast Harbor.

When Rozendaal purchased MADDY SUE, she had a 1960s six-cylinder Chrysler, essentially a marinized truck engine. Because spare parts would be difficult to find, Rozendaal replaced it with a rebuilt Chris-Craft flat-head, six-cylinder engine of about 140 hp.

Peter Rosenfeld, a retired electrical engineer who joins interesting projects at Darling’s from time to time, rewired MADDY SUE, converting her original running lights for LED bulbs. He also devised two laser-aligned jigs to aid in installing the new engine bedlogs and shaft bearings: One was a box with arms corresponding to the engine mounts that allowed accurate positioning of two holes aligned with the engine’s output shaft, and the other provided a final check on the engine’s alignment before installing the drive shaft.

DOUGLAS BROOKS

The original mahogany cabin sides were restored and varnished. The original painted decks had been impossible to keep watertight, which caused significant decay within the hull. Her replacement decks are plywood sheathed in fiberglass cloth set in epoxy.

MADDY SUE was relaunched on a raw and gusty Memorial Day weekend at Point Bay Marina on Lake Champlain. In conditions reminiscent of a Maine northeaster, a crowd of friends and family were there to watch Mary Jane Rozendaal break a bottle of champagne across the bow. To those present, there was much appreciation of MADDY SUE’s lines and proportions, qualities that were obvious to Rozendaal and Darling when they first saw her rust-streaked hull in the boathouse on Cranberry Island.

“Boatbuilders have an aesthetic,” Lunt said. “Raymond Bunker told me the tumblehome is what made a boat pretty. He said it had to be there.” As for Clement, boatbuilder Robert Rich told Lunt in 1970 that “Chester Clement had a little something the rest of us never had around here. It was here, it was in his eye.”

His eye and his hands. Clement, like most boatbuilders in Southwest Harbor, designed his boats by carving half models at either either 3⁄4″ or 1″ to the foot. The builders would measure their models and loft their sections full-sized. Stanley was the sole exception, designing his boats on paper. As for the other local builders, “They just took a block of wood and carved away everything that didn’t look like a boat,” Stanley said.

LARRY ASAM PHOTOGRAPHY

MADDY SUE is one of several classic yachts that Jan Rozendaal has restored. She lies to her mooring on Lake Champlain, Vermont, close by his Concordia yawl MOONFLEET. Rozendaal has also restored the N.G. Herreshoff–designed New York 30 MASHNEE, the Ralph Winslow–designed 24′8″ sloop HOTSPUR, and the 1956 Sparkman & Stephens–designed 35′2″ sloop CORLAER.

DOUGLAS BROOKS

In restoring the cabin, the windshield, and steering station, as much original material as possible was saved, and replacement mahogany was stained to match before varnishing.

There are those who can imagine a fair curve and make it a reality, starting with a half model and ending with a boat. There are those who grasp the same lines and appreciate the beauty but also recognize the intrinsic value in saving a boat that embodies such talent and skill. During the MASHNEE restoration, Charlie Langworthy, a boatbuilder at Darling’s, told Rozendaal that he certainly had an eye for pretty boats. Coming from a professional boatbuilder, it meant a great deal to him. “I’ve never forgotten that,” Rozendaal told me. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s the highest compliment someone can give me.”

The author would like to thank Dr. Richard Lunt of Potsdam, New York for the use of his thesis, “Lobsterboat Building on the Eastern Coast of Maine: A Comparative Study” (Indiana University, 1976) in researching this article. Meredith Hutchins and Charlotte Morrill of the Southwest Harbor Public Library supplied photos and information, as did Willie Granston of the Great Harbor Maritime Museum.

Douglas Brooks is a boatbuilder, writer, and researcher, specializing in traditional American and Japanese boats. See www.douglas brooksboatbuilding.com. He lives with his wife, Catherine, in Vergennes, Vermont.

Darling’s Boatworks, 821 Ferry Rd., P.O. Box 32, Charlotte, VT 05445; 802–425–2004; www.darlingsboatworks.com.