Ireland’s Water Wag

The original one-design

The original one-design

Ireland’s Water Wag–class dinghy pioneered the concept of one-design racing in 1887, and remains popular today. Here, PENELOPE, sailed by Fergus Cullen, has the windward advantage at the start of a race in the Galey Bay Regatta last year.

It was a breezy Wednesday evening on Dublin Bay, with a fresh northwesterly gusting to 25 knots and pushing up a chop as it rubbed against the north-going current. Competitors in a fleet of near-identical wooden Water Wag dinghies were vying for position at the starting line in Dun Laoghaire Harbour, prompting two general recalls. As they finally got away, the lighter boats cracked open their spinnakers and got up on plane, while others struggled to control their sails in the challenging conditions. Surprisingly, there were no capsizes or collisions during the four laps around the harbor, and the race ended up as a battle between two husband-and-wife teams: Cathy Mac Aleavey and Con Murphy sailing MOLLIE, and Guy and Jackie Kilroy in SWIFT, with former Olympic sailor Cathy clinching the prize by a few seconds.

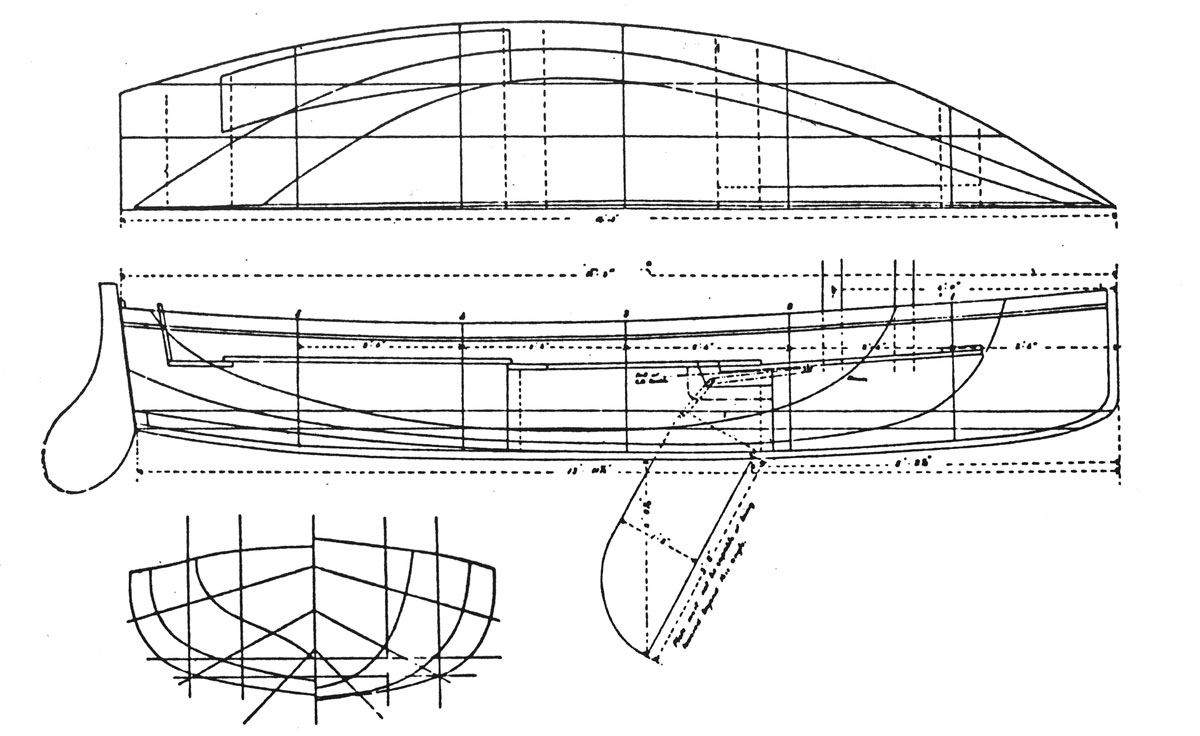

The Water Wag class began as a double-ended, or “Scotch-sterned” boat; by 1898, holes in the class rules led to the design of a transom-sterned replacement. The boat shown here is probably YUM YUM.

The Captain’s Prize Race on September 2 last year was a historic occasion for the Water Wags, as 28 boats raced together in what was the biggest gathering of the fleet ever. That’s an astonishing achievement for a class that pioneered the one-design concept 129 years ago and is now not only the biggest one-design fleet on Dublin Bay, but one of the biggest in the world. New Water Wags are still being launched almost every year, and century-old boats are just as likely to win races as brand-new ones. What, exactly, is the secret of this evergreen class?

The concept of building a fleet of identical boats to race together on equal terms was the brainchild of Dublin lawyer Thomas Middleton. Like many of Dublin’s newly emerging middle class, Middleton lived on the outskirts of Dublin, in Shankill, and commuted to his office in the city. A keen sailor, he crewed on yachts in the Royal Alfred Yacht Club and was later vice-commodore of the Royal Irish Yacht Club (both based at Dun Laoghaire). Yacht racing at that time was dominated by boats designed to rating rules or in mixed fleets under handicap. It was a rich man’s game, as designers and sailmakers were constantly trying out new ideas to gain an advantage, and it was said a yacht built in May might be “outclassed” by July. Middleton thought this approach was not only unaffordable but took the focus away from where it should be: on the crew’s sailing ability. On September 18, 1886, he put the following notice in The Irish Times:

It is proposed to establish in Kingstown [now Dun Laoghaire] a class of sailing punts with centre-boards all built and rigged the same, so that an even harbour race may be had with a light rowing and generally useful boat. Gentlemen wishing to consider the proposition can have full particulars on applying to M 589, this office.

He got no response to his ad, but a few weeks later sent a circular to “fully 50 different persons” in the Kingstown area, which spelled out his idea more clearly.

The start of a Wag race in Kingstown (as Dun Laoghaire was then known), around 1910. The boat setting off on a dangerous port tack (No. 5) is the original MOLLIE, one of the top boats of the 1940s, which was lost in a house fire in 1982.

From a racing point of view, although the fleet will not have the speed of the clippers of the Dublin Bay Sailing Club [which ran races for a mixed fleet of open boats], yet speed is only found by comparison, and as all the boats will be the same a true and most exciting race will ensue, a race where every boat will have the same chance, and which will call for throughout continued attention in order to gain every little advantage to be got in order to win, and not a mere procession of boats, and a race that will be a contest of the crew and not one of designers and sail-makers; a contest also that will be interesting to the shoregoing people as it will be a close one, and the first boat in will be the winner.

A meeting was held in Dublin on October 27 when the design brief was finalized. As the boats were to be launched from Killiney Beach in Shankill, they had to be light enough to be carried by two people and seaworthy enough not to be swamped by the surf. Middleton based his design on CEMIOSTOMIA, a double-ended Norwegian boat he may have seen while vacationing in Scotland. The boat was fitted with a metal centerboard, which allowed her to sail right up to the shore. Because the ’board could be removed, the boat could be carried easily up the beach. The dimensions decided upon were 13′ LOA, 4′ beam, and a 75-sq-ft lugsail. The boats also set a 60-sq-ft spinnaker. Having unknowingly but effectively transformed the future of yachting, the meeting was adjourned and the intrepid pioneers headed for the Ship Tavern on Lower Abbey Street (coincidentally, a favorite haunt of several characters in James Joyce’s Ulysses) for a well-deserved drink.

A few weeks later, Middleton sent a note to prospective owners asking for suggestions for a name for the new association and received 15 replies. The new dinghy design, named Water Wag, probably had an avian namesake, because there was a large population of wagtails on Killiney Beach. It likely had a second meaning, too, as the club’s members were generally good-humored, or “waggish.” Middleton set the tone when he sent out a call for the next meeting, “to muster the family and pass resolutions for their welfare and generally settle their plumage for next season.”

Leading by example, Middleton ordered the first boat, built not in Ireland but at the yard of Robert McAlister in Dumbarton, Scotland. (Recent research suggests the sail plan may have been approved by the great Scottish designer G.L. Watson, as an original drawing bears the Watson stamp on the back.) EVA, known as “the mother of the fleet,” was duly delivered in December 1886 and symbolically launched at Kingstown on January 1, 1887. She was followed by three more boats from McAlister, DOT, BRENDA, and YUM YUM, and an Irish-built boat, OOF BIRD, which was later found not to conform to the agreed-upon design. The first Water Wag race, and therefore the first one-design race in history, was held on April 12 off Dun Laoghaire, and won by YUM YUM. The 12:30 start was signaled by the chimes from the Town Hall clock, as it would be for the next two years, until the class purchased a starting cannon in 1889.

The transom-sterned Water Wag was the result of a commission given to Kingstown boatbuilder J.E. Doyle. The 14′3″ boat bears a strong resemblance to a 16-footer the builder’s 17-year-old daughter, Maimie, had published in The Yachtsman; nobody knows whether father or daughter designed the new Water Wag.

Thirteen double-ended (or Scotch-sterned, as they are known in Ireland) Wags were built in that first year, and a dozen more by 1890, and by the end of the decade more than 50 boats had been built—although the most that ever raced together was 24, according to a report in a contemporary newspaper. From the outset, the class attracted some big names, including the legendary William Fife, who built at least five Wags in 1889 and 1890. Indeed, two of the star boats in those early years were Fife-built: ROSE, which won 25 out of 39 races in 1890, an unbeaten record, and ELLA, which put an end to ROSE’s winning run the following year. Other famous owners included Erskine Childers, author of The Riddle of the Sands, and Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scouts.

The yachting author Dixon Kemp was a vocal supporter of the class, writing in 1900 in his Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing: “This class is the germ of the One Model Club and has well carried out its initial objects, viz restriction on an advantage of a long purse; preservation of selling value of the boat and the combination of a serviceable and racing boat.” He goes on to explain that Fife had to charge £25 per boat (compared to £15–20 by others) because “such small boats are not in his line, and it would not pay him to give his attention to them for less.” Bearing in mind this was around the time Fife was designing SHAMROCK I for the AMERICA’s Cup, he may have had a point.

The 1909 VELA is one of several boats recovered in the 1980s and still going strong. She finished fourth out of 13 boats in Division 1B in 2015, and is sailed here at the Galey Bay Regatta by Philip Mayne and his daughter, Kate.

But Middleton’s other primary purpose was just to have fun. “As the boat was never designed for speed,” he wrote, “the racing was not originally intended to be hard-down serious sport, but more a sort of friendly sail round a course in boats all alike.” Accordingly, Middleton said that the officers appointed to run the club—a “King,” a “Queen,” two “Bishops,” two “Knights,” and two “Rooks”—had these chief duties: “to get up as much fun and as many jolly water excursions as possible.” A few years later, the fleet was split into two divisions to give the less-experienced sailors a chance to win prizes, too. The First Division was made up of “all the old birds of the Club whose feathers are well oiled and who brim full of dead knowledge,” while the Second Division were the “young birds—flappers in fact—of the Club, who are only learning to hand, reef and steer.”

Middleton himself raced only for a few seasons before retiring to concentrate on shoreside activities, serving as Honorary Treasurer, Rook, Captain, and then President, until his death in 1931. His absence from the racing fleet was never fully explained, although, ironically enough, it may have had something to do with his purchase in 1889 of a yacht, ORIEL, which he raced with some success on Dublin Bay.

By 1898, holes were beginning to show in the class rules. Several boats had been built in cedar, which made for a lighter, more competitive boat but pushed the price up from £15 to £30. The number of boats on the water declined. It was time for a rethink. That year, the search started for a new, cheaper design that would be built to stricter rules. These new boats wouldn’t have to be as light as the originals, nor double-ended, because most of the fleet was now kept on moorings off Kingstown.

Maritime historian Hal Sisk sails GOOD HOPE, which he had built in 1976.

Kingstown boatbuilder J.E. Doyle was commissioned to come up with a new design and soon produced drawings for a 14′3″ transom-sterned dinghy with a gunter mainsail, a jib, and a spinnaker. The new boat bore a striking likeness to a 16′ design that Doyle’s daughter, Maimie, then just 17 years old, had submitted to The Yachtsman and which the magazine had published the year before with the comment, “nothing but praise can be given to this work.” To this day, nobody knows for sure if Maimie or her father designed the new Water Wag. Either way, Doyle’s initial quote of £18 10s to build the boat proved too expensive, and the order for the first four transom-sterned Wags went to James McKeown of Belfast, who quoted £14 10s per boat, plus £2 16s 10d for the sails.

The specifications drawn up for the new Wag were much tighter than those for the original. The resulting boats were heavier. Planking had to be of yellow pine, apart from the top strake, which was teak with a gold covestripe. Teak, oak, and American elm were used elsewhere, as was ash for the tiller, yellow pine for the floorboards, and spruce for the spars. Cost was limited to a maximum of £16 for boat and spars, and £3 for sails.

Another centenarian Wag, MARCIA, took part in the Irish Raid in 2012 with Whitbread Race veteran Sylvie Viant at the helm. (Viant is now director of the Transat Jacques Vabre Race.)

The new boats were an instant success, and by the end of the first season, 12 were competing regularly in the waters off Kingstown, soon rising to 20. A few changes were made after the first season—tweaking the sheer, increasing the mainsail area to 95 sq ft—after which the boat would remain essentially unchanged for the next century and more. What changes were made were incremental, the first being a new rudder design in 1908. The cap on cost was lifted after World War II, and after that came terylene sails in 1958; spruce planking in 1961; suction bailers, hiking straps, and buoyancy bags in 1971; and laminated booms in 1987. Today, epoxy is allowed for structural pieces, such as laminated knees, and a few boats use modern cordage such as Dyneema for stays and running rigging.

The boat’s success wasn’t appreciated by everyone, however. There were furious articles in the press about the dangers of one-designs stifling the development of boat design and reducing the work flowing to boatyards—a debate that continues to this day. But the class was anything but stagnant, and from the outset attracted some of the top sailors in the country. When Ireland sent its first team of sailors to the Olympics, in London, in 1948, all of them—Jimmy Mooney, Alf Delany, and Hugh Allen—were Wags. Likewise in 1952, when Alf Delany sailed a Finn at Helsinki, and in 1960 and ’64, when Johnny Hooper sailed a Flying Dutchman at Rome and a Finn at Tokyo. The tradition continues to this day, with former Olympic sailor Cathy Mac Aleavey, who raced 470s at Seoul in 1988, winning a Water Wag championship in 2015.

Swiss Olympic champion Albert Schiess finished second overall in the 2012 Irish Raid sailing MOLLIE II, built in 2005 by legendary Irish boatbuilder Jimmy Furey. Irish Olympian Cathy Mac Aleavey owns the boat.

So far, this has been an Irish story. But the Wag was to travel far beyond its home waters of Dublin Bay and develop substantial overseas fleets, largely due to the Irish habit of traveling all over the world. In 1906, Thornycroft of Singapore built six Wags for the Royal Colombo Yacht Club, with foredecks added to cope with the big seas of the Indian Ocean. That fleet eventually grew to 18 boats. Likewise, the Royal Madras Yacht Club built eight boats, which eventually grew to 21. Twenty more were built for the Port Dickson Yacht Club in Malaysia, and small fleets appeared in Singapore, Sri Lanka, Rio de Janeiro, and the Andaman Islands. There’s even a story of two men escaping the 1942 Japanese invasion of the Andaman Islands by hiding a Wag in the jungle and sailing 800 miles across the Bay of Bengal to Madras. It took them three weeks. Without doubt, for much of the 20th century, the Water Wag was a truly international phenomenon.

By the 1970s, however, the fleet in Dublin was depleted and the class seemed to have finally been overtaken by the proliferation of modern designs such as Fireflies, Flying Fifteens, Lasers, and Squibs. With the class centennial approaching, the Water Wag Association launched a policy of tracing old boats, buying them back, and refurbishing them for resale. Many of the boats had ended up in Limerick, and several more were found in Wales. At the heart of the drive was retired doctor Derek Paine, who not only restored several old boats but also, from 1985 to 1995, built four new ones. Thanks to this concerted effort, the class celebrated its 100th year in good shape, with 24 boats competing in that year’s Captain’s Prize race—the biggest turnout since the 1890s.

Nowadays, the class is as lively as it’s ever been, with its weekly Wednesday race off Dun Laoghaire regularly attracting more than 20 boats, as well as annual regattas on the Shannon and a trip to the Semaine du Golfe in Morbihan (see WB No. 225) last year—the first time the home fleet has traveled overseas. Two new boats were completed in 2015 and another is being built by John Jones in Bangor, Wales, for the 2016 season. Although an estimated 100-plus Wags have been launched since the class’s inception, numbers (and names) have always been recycled so Jones’s new boat will carry sail No. 47. To add to the confusion there are two No. 8s, as that number was reallocated to a new boat (BARBARA) in 1915 after which the original boat (EROS II, 1908) turned up in Wales in the 1970s. Returned to the fleet, EROS II now sails as No. 08.

The wags BARBARA and MARCIA share a quiet moment during the 2012 Irish Raid on the River Shannon.

The main concern now is whether enough skilled boatbuilders can be found to maintain the fleet to the required standard. As class president Vincent Delany puts it: “The future of the class depends on having access to the right boatbuilder to keep the boats maintained. If a boat is leaking, people get fed up and leave it; if the leaks get sorted, people keep it [the boat] and carry on racing.” With this in mind, the class has hired a shed in which 12 boats can be stored; owners can work on them together during the winter months. Improbably, 128 years after it was created, the Water Wag is on the rise again and is currently one of the most active dinghy classes in Dublin Bay. And, as Delany says, “Everyone wants to join a class on the rise.”

The 1915 MARY KATE II (No. 6, though she is confusingly flying No. 33 on her spinnaker) chases the fleet in the 2015 Galey Bay Regatta. She was recently restored by boatbuilder Dougal McMahon; the owner, William Prentice, chose to not stain the new planks the same color as the rest as he felt that was “dishonest.” The boat is sailed here by Ian and Jenny Magowan.

So why is the Wag still so popular? It’s partly due to the way the way the club is run. The original two divisions are now divided into three: Division 1A, for boats with a good chance of winning; Division 1B, for boats that might win if they get lucky; and Division 2, for boats that have no expectation of winning (according to one Wag I spoke to). As well as the three divisions, there are three series every year, and no boat is allowed to win a series more than once. In fact, with 38 trophies to hand out, the class has more prizes than boats, which is a smart way of ensuring everyone—old birds and young flappers alike—gets a prize. Or, as class captain David MacFarlane puts it, “We are focused not just on the people in front but the people at the back too, because the guys at the front will enjoy themselves anyway because they are winning races. We need to look after the ones at the back.” It’s a concept I’m sure Middleton would have thoroughly approved of.

I joined this year’s regatta at Lecarrow on the River Shannon and sailed on the 105-year-old MOOSMIE, which under the ownership of David MacFarlane has twice won the top Wag trophy, the Jubilee Cup, and finished third overall in 2015. While I had no sense of sailing especially fast (slightly the opposite, if I’m honest), it was an undeniably exhilarating experience racing in a fleet of (almost) identical boats. With three sails to play with, there’s enough to keep you busy at all times, and the sailing is competitive enough to always be challenging (last year’s top cup winners won by just one point in the very last race of the season; that’s how close the racing is). It’s everything, in other words, you could want from dinghy racing, combined with the sensual pleasure of sailing on a vintage wooden boat.

The 1915 BARBARA showed that age isn’t a barrier to speed as she stormed across Lough Ree in a 25-knot breeze during the 2012 Irish Raid.

My hosts were Cathy Mac Aleavey and Con Murphy, who have been sailing Wags for 10 years. Before that, they raced relatively fast, modern boats, such as Hurricanes, Lasers, Laser SB3s, Flying Fifteens, and 470s. Con finds the older boats have several advantages. “With Lasers you have to hike, so you have to have hiking muscles, whereas with a Wag you need more all-round fitness. A Laser SB3 is faster, and downwind it’s wild, but at the end of the day speed doesn’t matter, because speed is relative. I get as much pleasure winning a Wag race as an SB3 race, and it’s hard to win a Wag race. Wags are more social too, and there are more ladies in the fleet!

“One of the main differences with Wags is that you try to tack as little as possible because you lose two boat lengths with each tack, even if you roll tack, whereas with Lasers you can tack as often as you like without losing too much. That forces you to think ahead and only tack when you really need to. The kids find it difficult to do well in the Wags, because they’re too impatient.”

Looking at the 2015 Wag leaderboard is a slightly surreal experience, as so many of the top boats crop up again and again in the class’s history. Top of Division 1B, for instance, was COQUETTE, the very same COQUETTE that, with George Jones at the helm, won the Jubilee Cup 15 times between 1911 and 1942, and four more times in the 1950s and ’60s. And there’s the 1906 PANSY, nigh unbeatable in the 1970s and ’80s with Alf Delany at the helm, now raced by his son Vincent. Of the 28 boats that took part in last year’s record-breaking Captain’s Prize Race, 13—nearly half the fleet—were built before 1940. And while the new boats do seem to have a slight edge, the top three of each division include at least one pre-1940 boat.

The 2001 SWIFT (center), built by John Jones in Wales and sailed by Guy and Jackie Kilroy, won the Galey Bay Regatta and was first overall in the class in 2015.

Middleton can’t ever have imagined that his concept of a fleet of simple, identical, boats designed for friendly sailing around Dublin Bay would be stronger and more numerous than ever 129 years later. Yet it’s this very simplicity that makes the class so enduring and immune to the vagaries of fashion. Middleton’s thesis applies as much now as it did in 1887: “Speed is only found by comparison.” As for the future, the Water Wag’s plumage is settled and well-oiled, and will no doubt carry on swooping over the Bay for many decades to come.

Nic Compton is a freelance writer and photographer based in the U.K. He has written 10 books about boats and the sea, his most recent being Ultimate Classic Yachts (Adlard Coles, 2015). He sails a 22′ Nigel Irens–designed Romilly out of the River Dart.

The author wishes to thank to Cathy Mac Aleavey and Con Murphy for making it all so easy, and Vincent Delany, whose book, The Water Wags: 1887–2012, was a major source of information for this article.