Fairliner Torpedo Redux

Runabout restoration on the layaway plan

Runabout restoration on the layaway plan

Eighteen years ago, owner John Lisicich discovered the skeleton of a rare runabout—a Fairliner Torpedo—in the Gig Harbor, Washington, shop of boatbuilder Bruce Bronson. He purchased what was left of the boat, and over the next decade made monthly payments on an eventual restoration.

John Lisicich bounds into Bruce Bronson’s boatshop—literally bounds, like a kid running into a bike shop on his birthday—and hails his friend with unrestrained joy. “Happy Wednesday! Happy Happy Wednesday! How ya doin’?”

Western Boat Building Co., known primarily for rugged seagoing vessels, produced the Fairliner Torpedo between 1947 and 1951.

There’s 17 years of wooden boat history behind their relationship, and looking just at the raw facts, you might not expect it to lead to such an ecstatic greeting. Lisicich made monthly payments to Bronson for close to 10 years for a boat that didn’t exist, except in the form of a dismal skeleton stashed on a dark overhead landing in Bronson’s shop. Lisicich’s wife, Sharon, made him a shirt with a photo of a glorious mahogany runabout on the front with the caption MY DREAM. The back depicted the decrepit skeleton and the admission MY REALITY.

“John wore out two of those shirts,” says Curt Erickson, another friend with a key connection to this story.

But the dream finally has materialized, the reality is in the water, and it’s performing spectacularly. This is a story of boat lust gone wild, off the rails of reason, consuming prodigious stacks of cash and a large hunk of a human lifespan, and yet in the end, everyone’s thrilled. Not all wooden boat adventures end this way, of course, but when one does and it’s infused with such unblemished happiness, it makes you think: worth every risk, any price.

Lisicich admits to being “obsessive”—a trait apparent in both how he acquired his boat and how he cares for it.

NO KA ’OI is powered by a four-cylinder, 140-hp MerCruiser—a lighter and more powerful engine than the original six-cylinder Graymarine.

The centerpiece of the story is the Fairliner Torpedo, an improbable concoction of curves produced by the Western Boat Building Co. of Tacoma, Washington, between 1947 and 1951. Erickson, who has owned five of them, says just 32 were built. It’s a tightly composed boat, just 17′ overall, with a 6′ beam. The original base price was $3,150, which was $250 more than a new Cadillac convertible commanded in 1947. Western’s ads claimed a 38-mph top speed with the 104-hp, six-cylinder Graymarine. Bronson thinks that speed claim might have been slightly hyped, but there’s no question that the Fairliner was built to be fast. It was extremely light—the frames were of Sitka spruce, which in the long run turned out to be not so hot an idea. Even in its meager production run, Western kept experimenting with tricks to squeeze out more speed, such as the very small rudder on the boat that now belongs to Lisicich. This was another questionable design innovation, because when approaching a dock at low speed, Lisicich’s Fairliner steers...well, hardly at all.

Lisicich is a guy who snags on a chance encounter with an object or idea, which then erupts into an unrelenting passion. He once heard a rumor about a combination player piano and violin called a Violano Virtuoso that was in a home basement near Tacoma and might be for sale. He knocked on doors for more than two years trying to find it. He had the friend who related the rumor to him hypnotized twice, trying to improve the friend’s recollection of where this home might be. Finally he and Sharon made three “wanted” signs and strategically planted them at the freeway entrances near the neighborhood of the machine’s rumored existence. That worked: The owner called and he bought it.

“The way to get John’s attention,” says Sharon, “is to say that something is unavailable at any price, and impossible to find.”

The rebuilt boat is planked in meranti, which is less dense than the original’s Honduras mahogany skin.

“I’ve never wanted to have the things that other people have,” Lisicich says. “I’ve always wanted the things that were unique and different. I think it’s because I’ve always been a sales guy. I think I was born being a sales guy. The jobs I’ve had, the companies I was with, it’s always been a unique product. Anything you’re passionate about, if you can share that passion with somebody, then you can create that excitement about it: a boat, a car, a piano, a brand.”

He readily admits he’s an obsessive. Ask if there’s a downside to it, and he pauses maybe a second. “No, I don’t think so,” he says. Then, brightening, “Because it’s only about good stuff!”

One day in 1997 he was talking boats with his cousin and mentioned that he was thinking about buying a classic wooden Chris-Craft. The cousin, who had already keyed in on Lisicich’s fixation with rarity, said, “Oh, John, you’ve got to have a Fairliner Torpedo.” The cousin actually owned a set of plans for the boat, and gave it to him to copy. The next year Lisicich went to visit Bronson, who had a reputation as the man in the Tacoma area to see about building classic wooden speedboats. “I could do it,” Bronson said, “but why don’t you just buy mine instead?”

Bronson pointed up to the landing. There wasn’t much of a boat up there, just a falling-apart cage of frames, battens, and bulkheads with a few stray parts collected in an old Pennzoil box. But Bronson explained the process of building an essentially new boat by using the remnants of this old one for patterns. Erickson had brought him two of these Fairliner Torpedo hulks; he’d rebuilt one for Erickson and kept this other one himself. It sounded good enough to Lisicich.

“I won’t be able to get to it for a long time,” Bronson warned.

“That’s all right,” Lisicich replied. “I won’t be able to pay you for a long time, so I think we’ve got something in common.”

They worked out something resembling a layaway plan. “We paid him 300, 400 bucks a month for years and years,” Lisicich says. “Finally around 2007 or ’08 he said we’d paid him up, and he would have it for us next year. Well, it took him a little longer—like five years. But it got done.” Bronson recalls the last interval a little differently—only two-and-a-half years.

Bronson’s high standards are evidenced in the hand-painted “Fairliner” on the tachometer—a job he subcontracted to a friend.

It might be worth pausing here to note that Sharon Lisicich used to teach business math in college. John acknowledges that he is exceedingly fortunate to have married her—not only because she managed the family disbursements well enough to keep them out of trouble, but also because she has long tolerated his acquisitive quests, including this Fairliner foray. This is uncommon; the terms “business math” and “wooden boat” may never have slept together in any other household.

Bronson is a busy man, at least in part because of his own distracting passions. His shop is a motley conglomeration of several units in a nondescript warehouse storage complex in Gig Harbor, a bedroom town just across a narrow strait from Tacoma. His father was a boatbuilder, owner of the long-defunct Hollywood Boat Company in Tacoma. Bronson built hot rods for a living for some time before returning to his marine roots, but he didn’t quite purge wheels from his system. One wing of his shop is occupied by a ’37 Cord that he’s restoring with a modern powertrain. This is not for a customer, but for himself. The rest of the space is jammed with wooden powerboats in assorted stages of renovation—some are his, some belong to customers. He works alone, so big projects don’t get done rapidly. But they do get done with care.

Courtesy of John Lisicich

The boat, as found, served essentially as a source of patterns. The original frames were of Sitka spruce—which is light and strong, but not terribly rot-resistant. The newly rebuilt boat is framed in meranti; engine beds are of Douglas-fir.

“Bruce is an artist,” Lisicich says. “He doesn’t just go through the motions; he puts himself into these boats. Everything that comes out of his shop is perfect by the time it leaves.”

Bronson seems perfectly matched to this particular niche of the wooden boat trade. “I grew up around boats like these,” he says. “I’ve always loved them. This was a period when ‘Made in America’ really meant something. That it was the best, whether cars or boats. They’re still timeless, 50, 60, 70 years on.”

Ask Bronson what the problems are in rebuilding a Fairliner Torpedo, and he answers with a joke: “Pretty much everything.” But he’s not laughing. It’s not a joke.

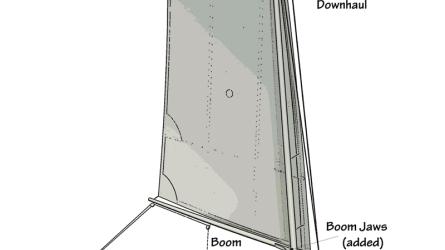

Spruce is terrific for spars and piano soundboards, but not for frames, which need a lot more strength, fastening-holding ability, and rot resistance than this wood offers. Anyone restoring a Fairliner Torpedo can expect to replace all of the frames with denser and more durable wood; Bronson used sawn meranti. The exquisitely pointy stern requires a laminated aft stem with chiseled pockets for the battens to nest in, and each pocket is cut at a different angle. Toward the stern, both battens and planks twist and bend in a demon’s fandango of compound curves. Rumor was that at the original Western boatyard they broke half the planks they tried to hang, though that’s likely another exaggeration. Still, Bronson cracked several. “It’s probably the toughest boat I’ve ever planked up,” he says. “There’s lots going on there.”

Courtesy of John Lisicich

NO KA ‘OI’s construction is fairly conventional for a runabout: She’s planked in the batten-seam method, with longitudinal stringers let into sawn frames and plank seams aligning with these stringers. No caulking is required in the seams, the result being an eye-pleasing wood-to-wood fit.

Bronson’s approach to classic-boat renovation tracks with his classic car philosophy. He wants the boat or car to look very much like the original on the outside, differing only in details a connoisseur might spot. But he’s not even close to a purist on any internal matters that affect performance, reliability, or comfort. His reasoning is simple: If the original builder had had access to superior technology, he would have used it. So Lisicich’s Fairliner, for example, got a four-cylinder MerCruiser engine, which is lighter and more powerful than the original; it also has freshwater cooling, rather than the original’s raw-water cooling. As he does with most of his runabout rebuilds, Bronson added a cockpit heater.

Bronson’s finish and detailing are at the level this Torpedo’s original intent deserves. The planking is meranti, less dense and somewhat easier to bend than the Honduras mahogany used for some of the original boats, but similar in color and grain. Bronson has fabricated a horizontal bandsaw so he can slide a 5/4″ board through it to yield two near-identical 5/8″ planks, and this allowed him to book-match the Torpedo’s planking, each side mirroring the other in grain pattern. The instruments are from a defunct Tolleycraft, but Bronson took the tachometer to a friend who is a master pinstriper and letterer, who hand-painted a tiny “Fairliner” in the dial to echo the original company logo. Lisicich thought the original plastic steering wheel looked a little cheesy, so he requested a banjo wheel. Bronson found one.

Courtesy of John Lisicich

The boat’s bottom has an inner skin of 1/4″ plywood (shown being applied above) and an outer skin of 1/2″ meranti. Between these layers is 3M 5200—a tenacious but elastic adhesive sealant.

Bronson completed the boat in 2013, or so he thought. He and the Lisiciches took it out for a first run, and it performed beautifully. Lisicich kept thinking he was maybe sniffing more hot oil than seemed appropriate, but there was no outward evidence of trouble. He and Sharon took three more day cruises that summer, and the oily aura persisted, but everything still seemed okay. They put the boat away for the winter. Then on their first outing in summer 2014, they were enjoying a good fast run, the ominous aroma creeping around again, and suddenly the oil pressure gauge plummeted to zero. They limped back to the dock at idle, and then on a trailer to Bronson’s shop. Oil, slung everywhere, slathered the engine space. The filler, valve cover gasket, and rear seal all were blown out. Burrowing into the engine, Bronson also discovered that the crankshaft was defective. He had used a rebuilt engine, but apparently it hadn’t been done well. Out it went for a re-rebuild.

The boat, named NO KA ’OI (Hawaiian for “None Better”) was finally launched again last spring. Lisicich is never at a loss for words, but relating his Fairliner’s life story has about drained his stock of superlatives by the time he gets to this second rebirth, and he is almost subdued when he’s asked to describe his feelings about owning it now. “Such a cool boat,” he says, quietly.

All of the boat’s hardware is original—cleaned up and rechromed for the restoration.

The Fairliner Torpedo seems as close to pure sculpture as any functional wooden boat can come. Yes, fiberglass boats can assume far more swoopy and extravagant shapes, and they do, but that very quality of infinite plasticity too frequently lures designers into the lurid realm of excess and vulgarity. A skin of wooden planks imposes a discipline. The boat must have an organic form, a shape developed in concert with the innate qualities of the wood itself. It’s as if the designer and builder negotiate a deal with the material, flattering it and wheedling it and wringing from it as many concessions as possible, but finally settling for a form somewhere within nature’s tolerance. This Fairliner is what we get if we take art and engineering and human ambition out to the far edge, as far as nature will allow. To move beyond this boat’s architecture, we would have to leave the organic world behind—for plastics.

The sculptural stern is the hallmark of the Fairliner Torpedo. The deck seams are caulked in white polysulfide.

Viewed on the water, the boat assumes a different personality from every angle. It’s remarkable how such a small boat can contain such a cast of characters. From abeam it looks remarkably cetacean, a hybrid species merging the snub bow of a sperm whale with the sleek, reverse-sheer body of an orca. Bow-on, it exudes menace, a hard, non-negotiating projectile. It’s at its most alluring in the three-quarter stern view, where the streaming-away teardrop form of the long aft deck suggests more engine than it actually enjoys (though Lisicich did briefly ponder transplanting a Chevy 350). The shape exudes the purity of purpose of a no-frills formula racing car, while at the same time the deeply varnished meranti planking breathes of luxury. It manages to be these two things at once without apparent contradiction. There are Art Deco details such as the stainless-steel cutwater, but overall the ornamentation is fairly restrained, considering the era of its design. The most amazing detail has to be the ineffably fluid transition from sides to deck. If it weren’t for the painted caulking between the deck planks, the whole boat would look as if it were carved from a solid block of wood.

From the forward cockpit, the token windscreen comes up to about lip level. It feels very much like a 1950s race car. Sounds like it, too—the engine grumbles and snarls with more baritone authority than you’d expect from four cylinders.

Underway, it could be a vintage racing car except for the fact that we’re carving through water. Acceleration is fast—another benefit of light weight—and remarkably tight, high-speed turns happen without drama or alarm. The designer was Dair N. Long, who collaborated with Western’s president, Allen Petrich, to create, essentially, a postwar sports car for the water. Petrich’s son, Allen Petrich Jr., says they “insisted on a design that if you were at top speed and turned the wheel as fast as you could in either direction, the boat would neither flip nor spin out.”

It’s an uncompromised design, an artifact from a time when boatbuilders did not employ marketing departments and focus groups. It’s generally impractical and totally unusable for most of the nautical activities boaters today want to indulge in—you can’t fish from it, tow a skier with it, or throw a beer party in it. There’s no stereo, swim step, or Bimini top. There’s no storage space whatsoever—if two passengers are occupying the aft cockpit, it will be tough even to stow a pair of fenders. But it’s this purity of intent that makes it a work of art rather than a willing appliance.

A Fairliner Torpedo is about two things, period: goin’ fast and lookin’ cool.

Lawrence W. Cheek is a writer, teacher, and amateur boatbuilder based on Whidbey Island, Washington.

Western Boat Building Co.

Petrich Family Collection

The Western Boat Building Co. was primarily a builder of large vessels. Among its most celebrated launches is WESTERN FLYER, the 72′ purse seiner immortalized in John Steinbeck’s The Log from The Sea of Cortez. WESTERN FLYER is currently lying in Port Townsend, Washington, decrepit but on the verge of restoration.

In 1968, the Fairliner Division of Western Boat Building Co. didn’t look like it was heading for oblivion. That year, Boating magazine’s directory of boating manufacturers listed Western’s array of 13 different motor cruisers and sportfishing boats from 26′ to 37′. But none of them were traditionally built; instead, all were being built with plywood hulls in an effort to compete for market share. In trolling today through that year’s directory, the trend is obvious: Fiberglass was in the ascendance. In the 1970 directory, Fairliner was absent. The name was sold to American Marine Industries in 1973, which from that point on built Fairliners in fiberglass.

Western, however, had enjoyed a distinguished run. It got its start in 1917 in Tacoma as a builder of commercial fishing boats, and it grew steadily in diversity and ambition. The fishing boats became quite large—the MARY E. PETRICH, launched in 1949 and named for founder Martin Petrich’s late wife, measured 150′ and was then billed as the largest tuna clipper ever built. It even included a chapel below decks. One of Western’s vessels, the 76′ purse seiner WESTERN FLYER, achieved literary fame when John Steinbeck accompanied a marine biologist on a collecting expedition aboard it and wrote The Log from the Sea of Cortez, his most important nonfiction work. (The boat, now severely deteriorated, is in the early stage of what the new owner estimates will be a $2 million restoration; see Currents, WB No. 245, page 18.) During World War II, Western built some 30 mine planters, minesweepers, and patrol boats. After the war the commercial division continued, branching into large steel-hulled boats and even oil rigs. And it launched the Fairliner division to concentrate on pleasure craft.

Martin Petrich’s son Allen was a racer, and the Fairliners pushed performance from its beginning. A 1948 magazine advertisement for the 26′ De Luxe Sport Cruiser touted speed of “up to 40 mph” combined with seagoing capability. “They take ’em out when others stay huddled in protected waters,” the ad claimed. Allen Petrich’s son Allen Jr. says a number of the big West Coast shipyards tried to punch into the postwar pleasure boat market, but he believes Fairliner “was about the only one to succeed.” For a time, he says, the division was the largest builder of pleasure craft on the West Coast.

Allen Sr. finally embraced fiberglass, but too late. He had a heart attack right around the time that plastic was swamping the pleasure-boat industry and sold the company. He died in 1981, just a little too soon to enjoy the full bloom of the wooden-boat revival. —LWC