Auto-Boats

The advent of the modern runabout

The advent of the modern runabout

DETROIT PUBLIC LIBRARY

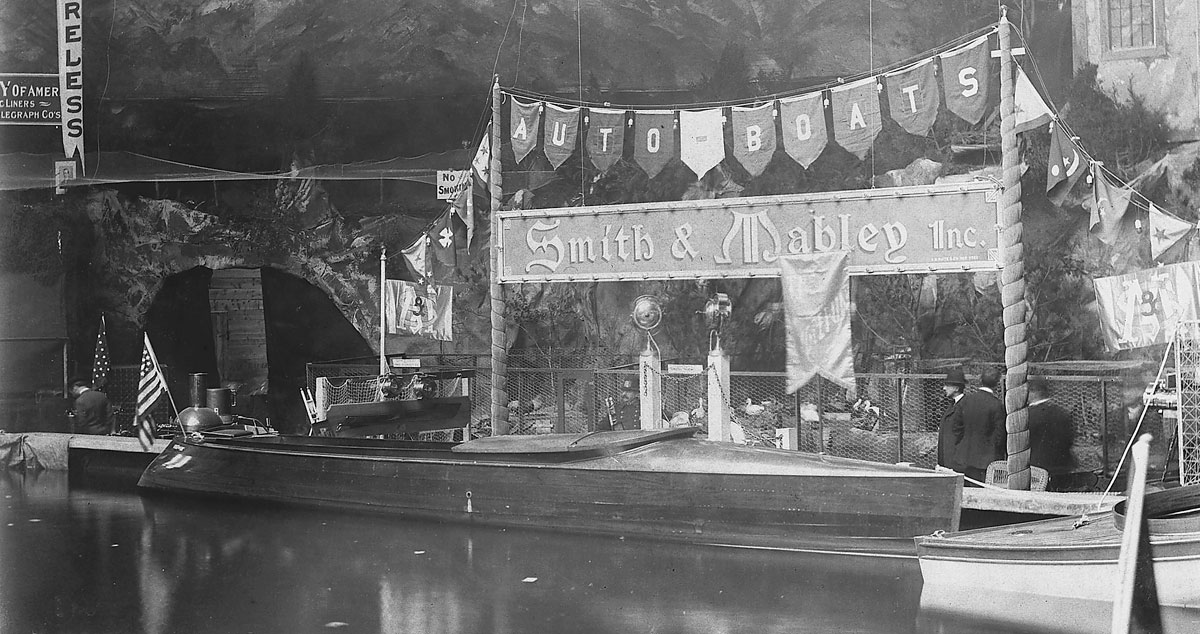

The introduction of the automotive element into powerboats produced a new type of watercraft. Automobile company Smith & Mabley, later Simplex, was among the first to enter the field and use the term “auto-boat,” as shown in this display at the 1906 Madison Square Garden Importer’s Salon.

In the July 1904 issue of The Rudder magazine, there’s an amusing firsthand account by L.A. Dixon of the optimistic purchase of a very early gasoline-powered auto-boat somewhere on the coast of Maine. “Last March,” writes Dixon, an experienced sailor who claims pure ignorance of powerboats, “the power boat fever struck me and it struck me bad, and nothing would help me any until I bought a gasoline launch.” The writer visits a builder (whom he identifies only as “Mr. H.”) and buys a 23′, 4-hp launch, with the intent to run it home. “I asked the builder to come aboard and start the thing for us, as I did not know the vaporizer from the flywheel. I kept a stern line out while he started her and then after he had jumped ashore I cut the line with my knife and started on the trip of 45 miles, with about 36 miles of it right out on the open ocean. As I passed out of hearing of the boatbuilder and his men I heard them singing ‘Mr. Dooley’, and that song, I think, I shall always remember.”

DETROIT PUBLIC LIBRARY

VINGT-ET-UN, later called “the first auto-boat,” is shown here in 1903 on the Harlem River, where she reportedly achieved a speed of 26 mph. The 770-lb, 21-hp boat was built for Smith & Mabley by rowing-shell builder Tom Fearon to plans by Clinton Crane.

Some boatbuilder! The tribulations of this pioneer can well be imagined. The piece captures well the enthusiasm and optimism for the union of the modern gasoline engine and the boat in 1903–04. The term “auto-boat” describes the resulting concept of light, powered launches—a new class of powered recreational boats driven by new technology and growing enthusiasm for the automobile. Though small recreational powerboats had existed for many years before 1904, the cultural revolution brought about by the automobile kick-started the powerboat industry we now know. The entry of the automotive element into the world of pleasure boating was fitful and controversial, but ultimately fruitful to the design of powerboats.

The icons of this new form of boat were the long-decked launches of the early 1910s, notable examples including the racing “Number Boats” (see WB No. 220). These are what we now mostly think of as auto-boats, as they so clearly show the automotive influence in design and layout, with their engines forward, passenger compartments with built-in, forward-facing seats situated behind windshields, automotive steering wheels and controls, and often convertible tops. These sleek semi-displacement launches are some of the most efficient, smooth-riding, and comfortable boats ever made, and for that reason they still have a following today.

The term “auto-boat” obviously derives directly from the automobile, a new contraption in 1904 that was rapidly transforming western society. (Interestingly, the term “automobile,” which simply means “self-moving,” had been in use for decades to describe self-propelled torpedoes.) The novelty of a self-propelled carriage after centuries of horses as the primary engines of movement over the road is easy to understand, but its impact is hard to overstate. The automobile was so visible that the transfer of its technology and terminology to boats made many more people aware of powerboats; in fact, many of them didn’t realize that small powerboats for pleasure had even existed before auto-boats, the automobile, and the gasoline engine itself.

The small power launches that preceded auto-boats occupied the same wilderness recreations as did many of the wonderful small craft produced in the last decades of the 19th century. With displacement hulls powered by steam, electricity, or naphtha, they were slow and meditative, well suited for seeing the sights and socializing. Most had either fantail or torpedo sterns, and open cockpits lined with benches under a canopy top. In the pre-auto-boat era, companies such as Lozier and Matthews also made gasoline-powered boats of this configuration—which, with their relatively slow speeds and parlor-like layouts, were not auto-boats.

DETROIT PUBLIC LIBRARY

Before the auto-boat, small, powered pleasure boats were primarily designed with open cockpits ideal for socializing in large parties. These mostly displacement craft moved at low speed, which was ideal for conversation, sightseeing, and eating cake, as this party is doing in Palm Beach in 1905.

One way to sum up the differences between auto-boats and the launches that preceded them is this: The early power launch was about <1>being somewhere; the auto-boat was about going somewhere—and fast. In fact, the sport of organized powerboat racing coincided with the adaptation of “automotive” gasoline engines to boats. One of the first to be called an auto-boat and receive wide publicity as such was a light speed launch called VINGT-ET-UN, designed by Clinton Crane and built by rowing-shell builder Tom Fearon for Manhattan-based automobile importers Smith & Mabley. The name, which means “twenty-one” in French, reflected the power of the new 21-hp Simplex engine by which it was powered, as well as the builder’s Continental connections and the fact that the French were a bit ahead in the development of both the automobile and the “auto-canot.” As the product of an automobile company, it was natural that it be called an “auto boat.” It weighed only 770 lbs, and in the fall of 1903, Smith & Mabley claimed a speed of 26 mph. Though it never actually raced, its 75-hp successor, VIGNT-ET-UN II, did, winning the second running of the Gold Cup in 1904 and several other races.

The Gold Cup is the major event of the American Power Boat Association (APBA), which was founded in 1904 essentially, if not explicitly, for the racing of gasoline-fueled boats—although gasoline boats would not exceed the fastest speeds reached under steam power until the 1910s. Nevertheless, at the start there was some consternation about whether the newer types of boats would be permitted. In fact, for this reason, there were two Gold Cup races in 1904, because the establishment was initially prejudiced against the lighter and less seaworthy auto-boats. Therefore, boats of the “VINGT-ET-UN type” were barred from competition in the first Cup race, which was won by the 60′ speed launch STANDARD. Poor competition in that race and the growing enthusiasm for auto-boats over the summer led to the second running in September, in which auto boats were allowed to compete. One of the victorious VINGT-ET-UN II’s notable competitors in that race was William K. Vanderbilt, Jr.’s HARD BOILED EGG (so named because “it could not be beat”), a 40-footer powered by a 60-hp engine transplanted from one of Willie K’s race cars.

DETROIT PUBLIC LIBRARY

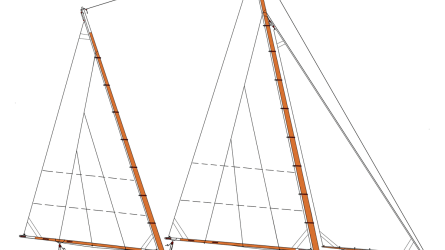

In 1904, the first year of the American Power Boat Association, a crowd inspects two racing auto-boats designed by Clinton Crane. VINGT-ET-UN II (right), driven by Proctor Smith, would win the second 1904 APBA Gold Cup while CHALLENGER (left) was the first American entry in the Harmsworth Trophy in England the same year. Though CHALLENGER showed superior speed at the start, ignition trouble caused her to fall behind.

It seems that a fundamental appeal of boating across all eras and cultures is the experience of self-directing—independently exploring the world and one’s place in it. In late-19th-century America, the philosophy of transcendentalism and the dense and poisonous landscapes of industrial urbanization drove people into nature and to boating, as they sought to find, in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s words, “an original orientation to the universe.” If the canoe and the early pleasure launch were products of transcendentalism, the auto-boat was one of modernism. The pursuit of freedom, luxury, and self-definition through new technology was in some ways an evolution of these ideals, and to some, a perversion.

W.P. Stephens, who chronicled the early years of American yachting, was a fellow canoeist and kindred spirit of Henry David Thoreau; he was as dismissive of the auto-boat as he was rhapsodic about the canoe. “[The auto-boat’s] origin is due neither to the naval architect, the marine engineer nor the yachtsman” (neither, it might be pointed out, is that of the canoe) “but to the restless and ambitious builders and owners of automobiles, who, about 1900, transferred the lightest and most powerful of their new engines from their proper place in the car to an improvised setting in some sort of a launch hull.”

COURTESY OF THE ANTIQUE BOAT MUSEUM

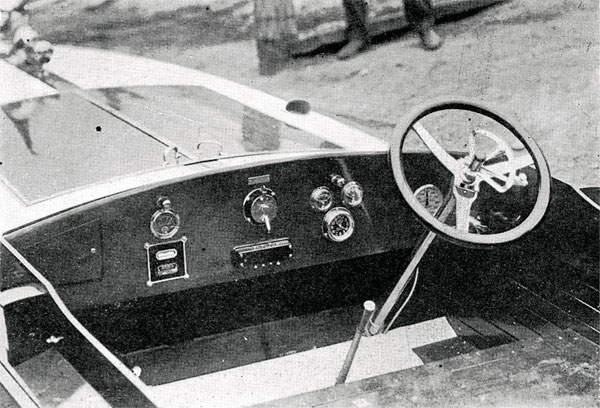

Auto-boats resembled cars in their controls, dashboards, automotive steering wheels, and even foot pedals, as shown in this advertisement from the Albany Boat Company. This styling was to become a long-lasting design element of powerboats.

The cultural tension between the makers and users of auto-boats and the long-standing tradition of yachting was palpable, and another reason why the press felt the need to give these new types of watercraft a distinctive name. In its first years, the auto-boat was simply a light hull designed for speed, fitted with an automotive gasoline engine. To the horror of the yachting world, generally very little science was used in the design and construction of their hulls. With some notable exceptions, the seamanship of those who were most captivated by auto-boats was often equally chancy. W.P. Stephens derided this new group of boaters as “automoboatists,” declaring that “…as a class they are utterly ignorant of practical boating and yachting as well as the elemental principles of naval architecture.” The yachting press declared the boats unseaworthy, a fair enough claim in many cases, but one that also revealed that the East Coast yachting establishment had a blind spot regarding the placid lakes, rivers, and streams of the nation’s interior.

It was on these quiet waters that the auto-boat really took hold. All around the country, boatshops sprang up to produce auto-boats, and local shops that had produced other small craft began to build small motorboats as well. Particularly in the Midwest, boatbuilders such as Matthews and Truscott used the principles of standardization and mass-manufacturing to develop stock models. East Coast builders such as Elco and Gas Engine & Power Co. (so-named in 1885, with the word “Gas” referring to naphtha) who were already building stock boats also quickly moved to produce auto-boats. This was a marked change from the culture of yachting, where new boats were generally custom designed and built. It’s no wonder naval architects were concerned: It seemed that they were destined to be left out of the present growth in boating as single designs were produced by the hundreds. Even worse, the innumerable small builders and backyard tinkerers who were fitting gasoline engines into all types of hulls were leading to more breakthroughs in powerboat hull design than were the naval architects. The same could be said for improvements to the gasoline engine itself.

Theory had not yet caught up to the principles of planing hulls, and while many of the best auto-boats were designed by naval architects, including Clinton Crane, Charles Mower, and Morris Whitaker, in some cases amateur practice was producing better ones. Accounts of the spectacular performance of unlikely-looking boats were mailed in to the boating publications from far-off places such as Wisconsin and Washington and dutifully published. The reporting of engine horsepower and speed was usually unverifiable. There was an excellent running spat, for example, in the pages of The Rudder from March through July 1904 between W. Albert Hickman, an unapologetic tinkerer who would later design the Hickman Sea-Sled, and naval architect Seth G. Malby about the merits of practice versus theory. It was sparked by an article Hickman wrote about his VIPER, at first glance a cracker-box of the worst kind, but apparently fast. At one point Hickman, gleefully occupying his role as the uneducated inventor, states “I read Mr. Malby’s article with great interest, but I had some difficulty in gathering its import, so I read it over to COCKAWEE’s cook. He said: ‘I think he’s mad with himself because he knows why VIPER does things and you don’t.’ That is doubtless the explanation.”

COURTESY OF THE ANTIQUE BOAT MUSEUM

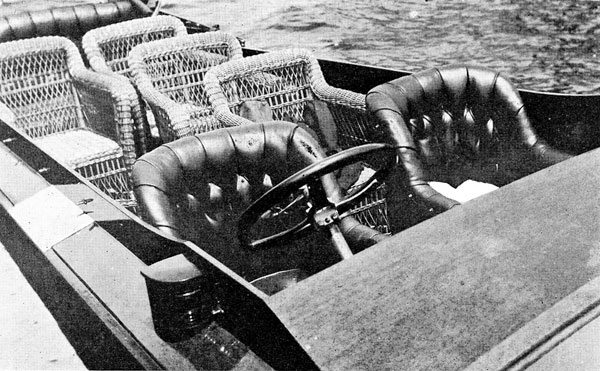

Unlike earlier pleasure boats, auto-boat cockpits were laid out like the passenger compartments of cars, with the driver in front, and forward-facing seats. This seems to suggest a shift in priorities, from socializing to speed.

Though the optimal design parameters were still being sorted out, the arrival of the auto-boat marked a great expansion in recreational boating and the boating industry. The National Engine and Boat Manufacturers Association was founded in 1904—the same year as the APBA mentioned earlier—and its first order of business was organizing elaborate trade shows for the sale of boats and their engines. It was a time when the technological enthusiasm of modernism was being culturally entrenched by consumerism, leading to the development of consumer gadgets of all kinds. Objects were being conflated with lifestyles through the power of advertising, and people were encouraged to define themselves and their level of success by their purchases. Expositions and trade shows of all kinds were fundamentally aspirational, and the makers of auto-boats drew on the visual language of Gilded Age yachting to sell their new class of watercraft as status symbols as well as amusements. The National Motor Boat Show very deliberately targeted new boaters, so much so that they had to display the boats in indoor pools to prove to the visitor that small boats would float safely.

The early auto-boats were chancy performers. Some managed to plane slightly while others did not. Some were exceptionally wet while others were reasonably dry. Some were cranky and others steered easily. Particularly when boats were designed for speed, it was hard to know how they would perform. Some of the first auto boats were torpedo-sterned, though most builders had switched to flat or V-transoms by 1910. Looking back, the principal difference between a successful boat and an unsuccessful one lay in the balance of weight, placement of the engine, amount of power, and shape of the hull. The famous DIXIE II, the most successful of the semi-displacement raceboats, owed its success in equal measures to Clinton Crane’s design and to the remarkable Crane-Whitman V8—perhaps the first large engine to achieve 10 lbs per horsepower.

DETROIT PUBLIC LIBRARY

Opulent trade shows were an important part of the transformation of the recreational boating industry during the auto-boat era. Shown here is the Lozier display (though not auto boats) at the 1905 Boston Boat Show.

Mass-production in boatbuilding is often lamented, though builders such as canoe-manufacturer Henry Rushton seemed to retain a fairly high level of craftsmanship despite it. I have often thought that true artistry requires a certain amount of ego on the part of the craftsperson, and standardization limits opportunities for this. Some of the younger companies in the 1900s were turning out auto-boats despite having precious little experience. In my former capacity as curator of the Antique Boat Museum in Clayton, New York, I was sent last fall to examine, for possible donation, a 1915 auto-boat built by Lawley. Designed by a young Walter McInnis, it was the venerable Boston yacht-builder’s attempt to enter the market for stock boats, and it debuted at the 1915 National Motorboat Show in New York. Its quality of construction over offerings of younger, inland builders was striking.

Around 1905–07, auto-boats began to resemble automobiles in design as well as power, partially because of the smaller and more reliable four-stroke-cycle engines—which could be placed under hatches and thus isolated from the passenger compartment. The layout, hardware, styling, and controls also increasingly mimicked those of cars. Spotlights, cushions, horns, and convertible tops became opportunities for extravagance. Indeed, this is the time when the form really came into its own, both in design and power.

COURTESY OF THE ANTIQUE BOAT MUSEUM

Racing auto-boats were difficult to handicap and often uncomfortable for daily use. This led the Thousand Islands Yacht Club to commission a one-design motorboat class in 1910, and the resulting “Number Boats” became some of the most successful and long-lived of the type. An example is shown at the far left in this frame.

Some of the most extravagant auto-boats were produced in this era. The Niagara Motorboat Company of Buffalo, for example, built some of the most elaborate auto-boats during the early teens. Two of these still exist, the larger one having foot pedals for forward and reverse, a brass spotlight controllable from the helm, deep cushioned bucket seats, and interior lighting. The engine is equally remarkable—a Fay & Bowen T-head with an aluminum crankcase and a beautiful brass oiler that could be monitored and accessed by the driver through a glass window in the mahogany dash panel. This engine is on loan to an equally remarkable 33′ torpedo-sterned, long-deck auto-boat, ANDANTE, built by Fay & Bowen in 1916. She is currently being restored at Tumblehome Boatshop in Warrensburg, New York.

The term “auto-boat” began to go out of fashion by the early 1920s, and was replaced by the word “runabout” for a fast pleasure boat with automotive power and styling. At about the same time, the hard-chined planing hull came to primacy, which necessitated a rearrangement of the cockpits. Where an auto-boat generally had a single cockpit with the engine forward, the runabouts of the 1920s had split-cockpit layouts with engines between them. The driver had to be farther forward in these bow-high planing hulls, and placing the engine farther aft allowed them to plane at lower speeds.

Though the name “auto-boat” is long gone, the trend it started continues. The small gasoline-powered boat still thrives, and is still influenced by automobiles in power, controls, and styling. The way the boats are manufactured, sold, and maintained has also continued to follow the automotive model. Racing has always played an important role in brand development, from Smith & Mabley to Chris-Craft, Gar Wood, Donzi, and Scarab. The on-again, off-again relationship with the science of naval architecture also continues, and these craft still provide an entrance into the world of boating for many. With a few notable exceptions, the days of the slow pleasure launch, concerned mostly with comfort, viewing scenery, and socializing, are long behind us. There is, however, one modern class of boats that harks back to the lovely fantail launches of 1890. But you, dear WoodenBoat reader, are not going to like it, because even though its purpose is similar to that of the early launches, it contributes nothing to the lovely scenery in which it operates. It is, of course, the outboard-powered pontoon boat, which, to the extent that it can be called a boat at all, serves a very similar purpose to the very first pleasure launches.

The automobile’s influence on the boating world has not always been positive, as the emphasis on speed and extravagance can obscure the more meditative and solemn rewards of boating. It is hard to see how the modern bow-rider helps a person find their “original orientation to the universe” through a connection with nature. Though they may share some of the blame for the more offensive modern powerboats, auto-boats don’t share the same flaws. They are elegant and gentle, quick when asked but perfectly happy at low speeds. I am heartened by the enthusiasm exhibited by a few collectors and shops for the type. Some of the moments in which I personally have gotten closest to understanding Emerson have been in auto-boats.

Emmett Smith is the former curator of the Antique Boat Museum of Clayton, New York. He wrote about Charles Mower–designed Number boats, a one-design class of auto-boats, for WB No. 220.