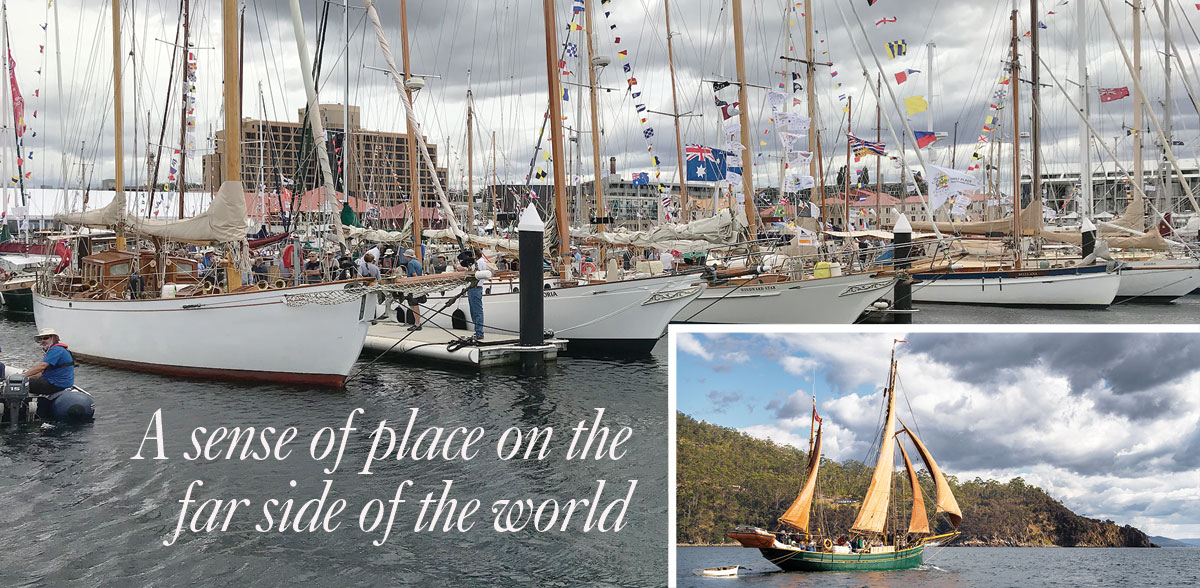

Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2019

More than 500 boats were displayed on land and in the water at the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in February. The biannual event covers the sprawling waterfront of Hobart, in the island state of Tasmania. Inset—The Danish fishing ketch YUKON, which hails from Franklin, Tasmania, makes her way to the festival-opening parade of sail.

“But it was not without regret that I looked forward to the day of sailing from a country of so many pleasant associations. If there was a moment in my voyage when I could have given it up, it was there and then….” —Capt. Joshua Slocum, meditating upon his departure from Tasmania in 1897.

On the morning of February 8 this year, the 60-ton Danish fishing ketch YUKON eased alongside a floating dock in the town of Kettering, in the Australian island state of Tasmania, to collect a load of passengers en route to the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in the nearby city of Hobart. A week or so before traveling from Maine to Tasmania, I had been invited to join this excursion, which would depart Kettering in company with the Bass Strait trading ketch JULIA BURGESS and several other vessels and wend its way out into the D’Entrecastaux Channel into the Derwent River and then north to Hobart, where we would to join the festival-opening parade of sail.

ROSE, a couta-boat-as-pocket-cruiser designed and built by her owner, Jeremy Clowes, and launched in 2009, blasts along in a 25-knot breeze off the Hobart waterfront.

That invitation was a pleasant surprise. WoodenBoat had published an article about YUKON in 2011, and the vessel, since then, has stuck with me as one of the most impressive restorations we’ve covered. Her owner, David Nash, an Australian, had purchased her for a case of beer while she was lying on the bottom of DragØr Harbor in Copenhagen. Raising and heroic restoration ensued. And during the project, a romance between David and his partner, Ea, blossomed into a family. When we left the young family at the end of that article eight years ago, they were embarking, in YUKON, upon a circumnavigation.

I did not know that YUKON was now based in Tasmania when I began planning my recent trip. But I should not have been surprised: As I had learned when I attended it in 2007, the Australian Wooden Boat Festival is not so much a celebration of local boat types—though there is plenty of that as it is a gathering of fine boats and vessels from all over the planet. In 2007, the organizers had hosted staff boatbuilders from the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, and transported several reconstructions of Viking-era boats to Hobart for display. In 2011, they brought in a 42′ three-masted traditional Japanese boat, along with a crew of eight oarsmen. This year they celebrated the United States by flying in a corps of builders from the Northwest School of Wooden Boat Building in Port Hadlock, Washington, along with a crew of other American artisans and luminaries that included keynote speaker Jon Wilson, this magazine’s founder. The builders, led by the school’s chief instructor, Sean Koomen, built a Joel White–designed Haven 121⁄2 in the months leading up to the festival, and they had this and another partially built one on display.

As YUKON approached Hobart, the breeze was blowing a steady 25 knots and there were boats everywhere. Classic Australian harbor launches porpoised through the building chop, while the Maine-built lobsterboat BENITO (see WB No. 227) powered right through it. Couta boats—distinctly Australian fishing sloops turned racing boats—crossed tacks with slippery cruising trimarans. In the distance, at anchor, lay HM Bark ENDEAVOUR, the replica of Capt. James Cook’s ship of exploration. In company with ENDEAVOUR was the three-masted steel bark JAMES CRAIG. A thousand yards to starboard was what appeared to be a Sparkman & Stephens sloop with its mast sheared off at the spreaders—but valiantly motoring along with the parade, nonetheless. (I later learned that a failed chainplate was the culprit.) I was standing amidships on YUKON’s deck, observing all of this, when suddenly, under the main boom, there appeared the distinctive profile of a 12-Meter sailing through our lee, under mainsail alone. This was the 1970 Australian AMERICA’s Cup challenger GRETEL II, the last of the wooden AMERICA’s Cup 12s.

GRETEL II, the Australian challenger for the 1970 AMERICA’s Cup in Newport, Rhode Island, zips through the lee of the ketch YUKON en route to Hobart.

ENOUGH, a Lapworth 50 built by American Marine in Hong Kong, is carrying the Ashton family of four on an extended cruise from their home in California. “Everyone in this hemisphere has said ‘You have to come to this show!’” says her owner, Geoff Ashton.

It was a grand show-opening spectacle. Because of the swelling fleet and strong breeze, things could have been tense on YUKON’s deck. But YUKON is a stable boat, and David, who was at the helm, is a stable man. Both vessel and crew took the conditions in stride, and the passengers followed suit. As we struck sail and headed for our berth in Hobart, David sang out: “Watch out, here we come.” A chorus of laughter erupted among the guests.

Watch out, indeed. In a recent article for Signals, the house magazine of the Australian National Maritime Museum, one of the festival’s co-founders, Cathy Hawkins, wrote, “The long weekend flies by in a blur of logistical tasks, so it’s hard to experience the event as visitors and other boats’ owners do.” Knowing what I know now, I don’t think any two boat owners or visitors have the same experience at the festival, either. There are simply too many boats, too many displays, too many talks, too many old friends and new ones, all creating a captivating panoply of choice and chance, for anyone to experience this festival as a linear, prescribed narrative.

Here, then, is a little slice of how my long weekend in Hobart unfolded.

The 44′ lobsterboat-yacht BENITO is a regular attendee at the Hobart festival. She was built by Peter Kass of South Bristol, Maine.

“Everyone in this hemisphere has said ‘You have to come to this show!’” That’s what boat owner Geoff Ashton told me after inviting me aboard his sloop-rigged Lapworth 50, a former thoroughbred ocean racer that he and his young family have repurposed for extended cruising. His boat, ENOUGH, was built by American Marine in Hong Kong for the TransPac Race in 1962. The Ashtons, who are American and have been cruising in her for five years, have kept ENOUGH very original.

Before cruising, Geoff was a merchant mariner, and his wife, Miriam, worked in technology. We fell into an easy conversation about their boat, their lifestyle, and their former lives. And that’s how I learned that Geoff had attended Maine Maritime Academy in Castine—a very small Maine coastal village surrounded by even smaller coastal villages. I live in one of the smaller ones, and you can’t drive to the academy without driving by my house. “All this way to talk about Maine,” Geoff said with a chuckle.

Three Lyle Hess cutters lie in Constitution Dock, the heart of the in-water exhibition. The diminutive bluewater boats are popular in Tasmania, thanks in part to several recent constructions at the Wooden Boat Center in Franklin.

The state of Tasmania is almost exactly opposite from Maine on the globe. Put another way, Tasmania is about the farthest you can get from Maine on the Earth’s surface before you start coming home again. (The true geometry actually puts Maine’s so-called antipode somewhere in the water southwest of Perth, Australia, but it’s close enough to make the point.) And yet, the affinity between the two places, when you stir in a passion for wooden boats, is mind-boggling. Consider, for example, BENITO. She is a 44′ lobsterboat-inspired yacht built by Peter Kass in South Bristol, Maine, for Tasmanian owner Will Baillieu. I expected to see this boat there. Baillieu, after all, had commissioned her with Kass specifically for export to Australia, and she had appeared on the cover of this magazine in 2012 (W B No. 227). But as I sat in her saloon reviewing the story with him, it was nonetheless eerie to learn that the settee in which I was perched was modeled on the booth-seat design of the South Bristol (Maine) Diner, where Baillieu and Kass had worked out many details over lunch.

I would venture to say that there were more American yacht designers represented at this event than at any other I have been to. In addition to this Peter Kass lobsterboat and the aforementioned Bill Lapworth sloop, there were boats designed by Fenwick Williams, Ralph Winslow, Olin Stephens, L. Francis Herreshoff, Joel White, Lyle Hess, and John G. Alden. The Alden examples were particularly interesting: One was a 41′4″ Malabar I called CAPELLA II—the sole surviving example of the design (the original of which was built in Maine), the owner, Byron Bennett, told me. He’s had her for eight years and had just relaunched her after an eight-year structural refurbishing. She was built in California, but has been in Tasmania since 1986. The other Alden was the 64′ ocean-racing schooner MISTRAL II, which was on a trailer, out on the street, heralding her forthcoming restoration by the Windeward Bound Trust, which will use her for youth sail training.

The 41′ schooner CAPELLA II, reportedly the last-surviving example of John Alden’s Malabar I design, has been in Tasmania for more than 30 years. She was built in California.

One of the best-built, best-kept boats of the in-water fleet was Tolly and Josephine Jaworski’s GLORIA OF HOBART, which Tolly built to L. Francis Herreshoff’s Mobjack design over the course of 20 years beginning in 1988. She is impeccably built and finished, with most of the timbers having been harvested in Tasmania. The planking is of Tasmania’s legendary “King Billy” pine, which is roundly considered to be one of the best planking woods in the world. Tolly just happened to get some of the last of it, before cutting was banned due to scarcity. Tasmanian boatbuilders, I would learn, are deeply committed to sustainable forestry—perhaps none more than Andrew Denman.

Andrew is a boatbuilder from Kettering who is currently restoring TE REPUNGA, a 32′ cutter-turned-ketch that in the early 1930s carried the legendary sailor George Dibbern from his native Germany to New Zealand. The tired hull has been accurately scanned inside and out in order to restore her shape. That commitment to exacting detail was what drew me in to Andrew’s story, and as I listened I just assumed he was, say, the third generation of this Denman operation. So I was rather shocked to learn that, in the summer 1999, he was an air traffic controller thinking about a career change.

The 41′ motorsailer JANE, designed by Ken Lacco and built by Tim Phillips at the Wooden Boat Shop, has a sprung keel in the style of couta boats, which are one of Phillips’s specialties. Powered by a 110-hp Yanmar, she has a range of 1,000 nautical miles.

That’s the year he discovered a copy of WoodenBoat (No. 156), which included an article on the wooden boat building school in Franklin, Tasmania. That planted a seed, and several years later Andrew’s urge to build boats was irresistible. He scoured his house for the magazine, found it, and finally enrolled in the school in 2003; he hung out his shingle in 2005, and never looked back. “Tasmanians didn’t realize what they had; it looked normal to them,” he said, recalling that the sight of traditional boats was commonplace back then. Andrew, however, recognized that such boats were in decline. I was further astounded to learn that he was currently putting the finishing touches on a Center Harbor 31, which is a 31′ daysailer-weekender designed by Joel White just a mile from WoodenBoat’s Maine headquarters. I was learning all of this as Joel’s son, Steve, was preparing to speak, at the other end of the show venue, about Brooklin Boat Yard’s latest projects.

While it’s impossible in this space to do justice to the more than 500 boats in display at the festival, here is a sampling of some of the representative Australian types on display.

Couta Boats

Couta boats (see WB No. 137), so named for their pursuit of the barracouta (not to be confused with barracuda) fish, were developed in the late 1800s for the rough waters off Bass Strait. They were among the last boats in Australia to work under sail only. Their numbers peaked in the 1920s but diminished after World War II with the widespread use of marine diesel engines. For the past several decades, couta boats have enjoyed a resurgence in popularity as classic pleasure boats. This charge has been led by the boatbuilder Tim Phillips and his crew at the Wooden Boat Shop in Sorrento, Victoria.

Piners Punt

Piners’ punts (see WB No. 253) were open rowboats used to transport Huon pine workers and their equipment on Tasmanian rivers. The boats likely originated in Port Davey or on the Huon and Picton rivers, where the Huon pine industry was well established by the late 1800s. They have ample rocker for easy maneuverability, for they had to negotiate river rapids. They were slack-bilged but beamy, so fairly stable.

Derwent Class

The Derwent Class is a one-design sloop designed by A.C. Barber, who was a naval architect in Sydney. The class was the result of a late-1920s design competition seeking a simple and inexpensive inshore one-design. By early 1928, a small fleet of these boats was racing regularly, and providing a conduit for fledgling sailors from dinghies to keelboats. Nine of the boats were displayed at the festival—all from Kettering.

ENDEAVOUR

HM Bark ENDEAVOUR (see WB No. 152) is a replica of the vessel in which Capt. James Cook charted the east coast of Australia—and much of New Zealand. When launched in 1993, she was roundly considered to be one of the most authentic replicas in the world. Indeed, one need not squint away too many modern items in order to see and feel what Capt. Cook and crew did in the 1760s. The wreck of the original ENDEAVOUR may recently have been discovered on the bottom of Newport (Rhode Island) Harbor, where she was scuttled by the British during the Revolutionary War.

PREANA

The steam yacht PREANA (see Currents, WB No. 244), built by Hobart’s then-premier boatbuilder, Robert Inches, in 1896, is likely the sole surviving regional example of her type. It was originally the private launch of one W.G. Gibson, who was a flour miller, and later was a familiar sight on the Derwent River, where it was used as a race-committee and rowing-umpire’s boat. PREANA went through a succession of local owners, and its original Simpson, Strickland & Co. triple-expansion steam engine was replaced with an internal-combustion engine in the 1930s. When the current owners purchased it in 1992, the yacht had sunk and was in need of thorough restoration. That project, completed in 2010, brought PREANA back it its original configuration, and included an American-built steam engine.

Matthew P. Murphy is editor of WoodenBoat.

For more information on the Australian Wooden Boat Festival, including a directory of all boats exhibited (complete with photographs), visit www.australianwoodenboatfestival.com.au. Senior Editor Tom Jackson’s reports on two previous Australian Wooden Boat Festivals appear in Currents in WB Nos. 244 and 256 and online at www.woodenboat.com/impressions-hobart-2017.