Antarktische Wildnis: Südgeorgien

Antarktische Wildnis: Südgeorgien, by Thies Matzen and Kicki Ericson. Mareverlag GmbH & Co. oHG, Pickhuben 2, 20457 Hamburg, Germany. 168 pp, illus., £38.87.

The cover of WB No. 255 features Kicki Ericson aboard the diminutive sloop WANDERER III of the island of South Georgia in the southern Atlantic. Kicki’s husband, Thies Matzen, writes about WANDERER III in that issue, and together the couple published a book of photographs and essays of barren, beautiful South Georgia in 2014. Editor Matt Murphy’s review of that book (published in WB No. 248) Antarktische Wildnis Südgeorgie (Antarctic Wilderness South Georgia), is presented here.

More than 30 years ago, a young German man named Thies Matzen purchased the 33′ wooden sloop WANDERER III, made famous by the British cruising couple Eric and Susan Hiscock. He then embarked upon a remarkable life afloat in the already well-traveled boat. Along the way, he met and married Kicki Ericson; in more than 25 years of sailing together, the couple has journeyed to some of the world’s most remote places. WANDERER III, launched in 1952, has now logged more then 300,000 nautical miles—many of them under Thies and Kicki’s ownership.

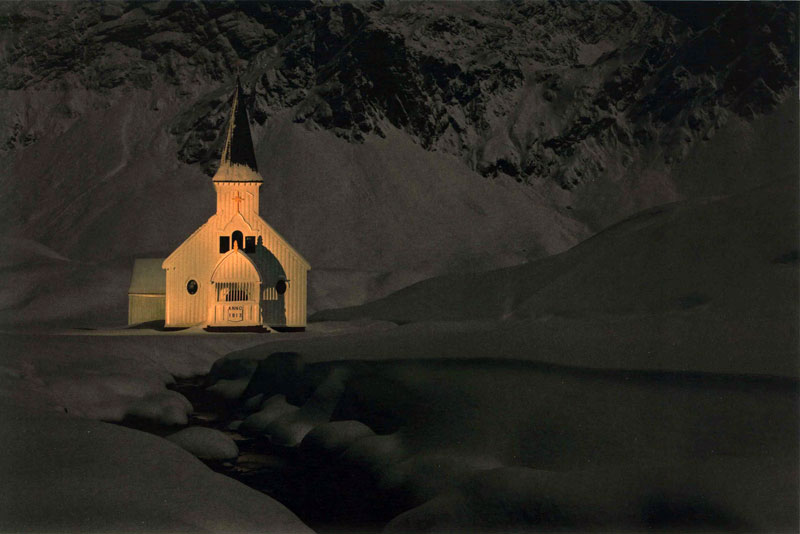

The Norwegian whaler’s church at Grytviken, an abandoned whaling station.

None of their destinations has been more spectacular than South Georgia, the lonely Southern Ocean island located halfway between the Argentine coast and the Antarctic continent. Thies and Kicki have visited the place on two occasions—the first in 1998, for three months, during which time they were married at the Norwegian whaler’s church at the abandoned whaling station called Grytviken. Those three months were too little time for them.

“Does time slow down in winter? …Do high and low pressure systems move more slowly in winter than in summer? It seems so. It is so much nicer, lonelier now than in the haste of the summer season when eye-people reach the island. In the darkness of winter we admire with our ears.”

And so they returned in 2009, intending to spend a full year. “We weren’t an expedition,” Thies writes in the introduction to their book, Antarktische Wildnis: Südgeorgien (Antarctic Wilderness: South Georgia), an account of their time on the island told through photographs and lyrical captions. “Our only wish was to be here. More than anything I was attracted to South Georgia’s winter: to see the island clad entirely in white, whether in serene majesty or lashed by blizzards…. All is wind and the magic of a remoteness that will not be broken for over half a year.” They spent midwinter at Grytviken, which they describe as the safest place for a boat during those months—and also the place with the best skiing. A mile away, a British research station houses the island’s entire winter population of ten. Spellbound by the spare beauty of South Georgia, Thies and Kicki decided, after their first winter on the second trip, that they needed even more time on the island and extended their stay an additional 14 months.

“From the cockpit I hear the interrupted breathing of an elephant seal. At first I can’t see him, then I discover his polished moving shape close to the hull of the PETREL.”

They not only endured their 26 months on South Georgia. They thrived, reveling in the solitude and spellbound by the wildlife. Kicki writes:

Thankfully any worries I may have had about boredom or hardship during a winter in these lonely latitudes never came to bear. In fact both Thies and I feel the time flew by much too quickly. And we ate like kings, having both fresh and dehydrated fruit and vegetables throughout, and even managed to uphold our daily-fresh-salad routine. Not to mention all the home-canned and pickled meat I had made in the Falklands. Cabbages, apples, carrots, onions, pumpkins, and my home sprouting of seeds saw us through the winter.

Thies is an accomplished photographer who has written on numerous occasions for this magazine, and his sensitive images of landscape and wildlife are the book’s principal illustration. Kicki relays her impressions and descriptions through excerpts of letters written to friends. The result is candid, raw, and unassuming—like South Georgia itself.

“Two or three chicks reveal themselves by chirping. A trumpet call is echoed from an unexpected corner of the colony—a duet: ‘I went fishing’—‘I have an egg’—‘I went fishing’—‘I have an egg’, until they find each other, fall silent, and let a moment of time infuse their brief togetherness.”

In fact, the book is remarkably focused in its editorial mission. How tempting it must have been to tell the history of WANDERER III, to publish her lines, to fill a chapter with archival and contemporary portraits of her. How tempting it must have been to tell tales of getting there and back, to impose a narrative arc on the experience, to focus it on the seafarer-authors. But this is no cruising narrative: There are few sea stories, and the select few photographs of WANDERER III are chosen to deliver a description of South Georgia—its vastness; its calmness; its fury. No, this is no adventure book; rather, it’s an impressionistic documentary told from a perspective made possible by a minimally equipped wooden boat.

The book is, in fact, poetry—both of the visual and literary sorts. There’s a striking image on page 128—a stern view of WANDERER III with taut mooring lines stretching to windward, the boat heeling more than 35 degrees to a… what…? 50-knot breeze, the sea a froth of whitecaps. Opposite that image, on the same spread, is a serene view of the golden-lit cabin, with everything in order, and Thies and Kicki writing and reading (see pages 23 and 24 in WB No. 256 for these images). “WANDERER III,” writes Thies, “is our only home, it carries everything we own and need. We don’t want to enlarge it. A small boat with a big history: 62 years old, harmonious, simple, and capable…without electronics, communication, or weather forecasting, we retain a fragility that I see as an enrichment. I believe it lets us read natural networks more easily. We become a tiny part of larger spheres and fit in.”

The book was published in 2014, in German. Last year an insert was added, delivering the text in both English and Chinese; it translates the foreword, the introduction, the photo captions, the epilogue, and the authors’ biographies. The mechanics of reading the supplement while paging through the photographs is not awkward, and it’s certainly worthwhile, for it allows a glimpse into a remote and beautiful place as rare as the animals that live there. That rarity is striking, as told in this essay on page 77, accompanying a photograph of a pair of Arctic terns standing against a majestic alpine background:

We saw maybe 200 or 300 of the 130,000 Antarctic terns that exist worldwide. Maybe seven of the 400,000 leopard seals, one of the 2,000 blue whales, 80 of the striated caracaras—every animal that we meet is a specimen of its species that exist in the thousands, hundreds of thousands, more rarely in the millions. They are relatively small groups. All the king penguins of the world, maybe 1.5 million, would fill Copenhagen or Hamburg…. I don’t actually know what I want to say. But in comparison the seven billion individuals of the species Homo sapiens 130,000 terns seems vanishingly few.… But humans live globally, everywhere, in every habitat, whereas these terns only in this one.

“A hundred thousand Hellos, they don’t call a name, they simply call Hello. Would I recognize the voice of my mother amongst 100,000 voices, here, in a storm?”

I’ve maintained a correspondence with Thies and Kicki over the years, and even had the good fortune to visit with them in Whangerei, New Zealand, when they had WANDERER III hauled out for a major refit. In 2011, they visited my home in Maine, when they’d come to the United States to receive the Cruising Club of America’s Bluewater Cruising Medal—the club’s highest honor.

So, in the interest of full disclosure: We’re friends. The conventional wisdom is that with familiarity comes bias. But with it comes an understanding, too. A detached reviewer might apply worldly cynicism to this appreciation, written by Thies: “You know, Kicki, I would never have managed to keep track of our provisions. I would have forgotten most things, perhaps not the oats and coffee, but certainly the treats. We have a good life in our 9 square meters, and how many people would claim that life in so small a space can be so good?”

I’m here to tell you it’s authentic, and true. And this rare couple, sailing this rare boat to this rare place, have created a rare book.

Matthew P. Murphy is editor of WoodenBoat.

Antarktische Wildnis: Südgeorgien is available outside of Germany, with the English language supplement, on Amazon.co.uk. Search the German title, and not the English translation of it used in this review.