Aboard: ANNA

A 65′ Spirit of Tradition sloop

A 65′ Spirit of Tradition sloop

The sloop ANNA measures 65′6″ overall and displaces 57,000 lbs. She blends comfort, performance, and ease of handling.

The sloop ANNA is, effectively, a big daysailer—but one with elegant and comfortable accommodations for the occasional offshore delivery passage. Her designers, Paul Waring and Robert W. Stephens of the Belfast, Maine, design firm Stephens Waring, describe her as having “a hefty edge towards comfort, first and foremost, with a design brief that focuses on easy daysailing and entertaining of friends and family.” However, she is built of wood partly so she can compete in the popular Spirit of Tradition divisions of classic yacht races.

She was built by Lyman-Morse Boatbuilding of Thomaston, Maine—the first cold-molded yacht the yard has built. The process, however, employed some cutting-edge technology. As Tom Jackson described in his article “CNC Comes of Age” in WoodenBoat No. 261, “the hull was conventionally cold-molded over laminated wood frames and a few permanent bulkheads, aligned on a CNC-cut setup structure.” But the interior and deck were built in modules, off the boat; these modules included wire chases, plumbing, and finished joinery. When they were complete, they were lifted into the hull and set in place with minimal additional fitting required.

ANNA was launched in April last year and had a full season of racing and cruising in Rhode Island, Maine, and Nova Scotia. In the fall, she returned to Lyman-Morse for winter storage, and just before her haulout I joined her crew for a sail out of Camden Harbor on a brisk day in early October. The breeze was in the low 20 knots and the temperature was in the low 50s, and ANNA sailed beautifully. She was dry, stable, and responsive. She tacked and jibed easily and with minimal effort. She sailed close to the wind. And, as described on the following pages, she had a hefty edge toward comfort, indeed.

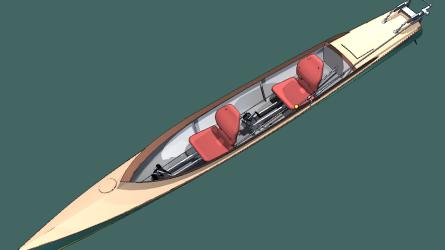

View from the Helm

The raised-deck main saloon, seen here from the helm, is the centerpiece of ANNA’s layout. Passengers can take shelter here from the cold or sun but still be a part of the conversation with the cockpit crew.

Versatile Cockpit Table

The instruments are cleverly hidden in the aft end of the cockpit table and are matched by a stack of drawers in the table’s forward end. Footrests built into the table’s base provide convenient bracing when the yacht is heeling. Simple angled brackets allow the table to be easily removed for varnishing.

Deck-Level Saloon

Martha Coolidge, an interior designer, fine-tuned the style of the woodwork detail, panel layouts, light fixtures, and other elements of ANNA’s appearance. The wiring for the LED overhead lights in the saloon runs through square fiberglass conduit let into the plywood-foam sandwich that composes the deck structure overhead. The electrically operated windows in the aft end of this space drop down, allowing easy communication with the cockpit.

The Galley

Four steps made of European walnut lead down from the saloon to the galley and the rest of the accommodation. While they would traditionally have been turned, the newel posts seen here were assembled from four CNC-machined sections. The raised paneling is bonded to a plywood substrate, for stability; its woven counterpart in the door to the left in the image is for the well-ventilated oilskin locker. The zinc countertops were fabricated by the Lyman-Morse metal shop.

Forward Stateroom

The owner’s stateroom occupies the forward space below. While most of the wood in the interior is either teak or European walnut, the owner’s berth is built of African mahogany to create a deliberately contrasting piece of furniture. The first layer of planking, seen here, is 5/8″ V-grooved fir, and was pre-finished before it was hung. This was followed by two layers of 3/16″ western red cedar laid diagonally, and a final exterior layer of 5/8″ Douglas-fir. The vents along the starboard hull-to-deck joint are for air conditioning; their styling is based upon the frame bay details of classic English yachts.

Molded Handrail

ANNA’s owners wanted anything they put their hands on to feel remarkable. The molded cabintop trim provides a distinctive, unobtrusive handrail reminiscent of yachts of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Headsail Handling

Stephens says that his firm has not designed a boat with an overlapping jib for many years. “In order to get the boat to sail close-winded with a genoa,” he says, “you need shrouds well inboard. The mast, stays, and hull must be engineered to handle the loads. Then there is the difficulty of wrapping the jib around the stays every time you tack.” A well-designed, non-overlapping jib, he says, allows the boat to be tacked simply by putting the helm over and winding in a couple feet of sheet. This is how ANNA is rigged, and her sheets lead to electric winches in the cockpit. Stephens reports that there are few conditions in which she’s slower than a yacht driven by a big overlapping headsail. ANNA also has a self-tacking headsail, the athwartships track for which is visible here forward of the mast. The shrouds are made of unidirectional carbon fiber encased in a woven shell for chafe protection.

Boarding Steps

The door in this photograph conceals a boarding step. Stephens Waring first designed such a system for the 90' cruising yawl BEQUIA, which they designed, although that door did not extend all the way up to the sheer. Lowering the hinged platform causes the steps to pivot into place.

Mainsail Handling

ANNA’s mainsail stows in the oversized boom. At this writing, plans were afoot to paint the boom in a two-tone scheme, to minimize its apparent size. It took the crew some time to learn to roll the sail smoothly on the mandrel, but this learning was worthwhile: the convenience of the system is undeniable for so large a mainsail (the total sail area is 2,040 sq ft). The sail is depowered by tightening the backstay, which opens up the leech.

Matthew P. Murphy is editor of WoodenBoat.