Stewardship

“You’ll find a good deal of original hull skin in any of the restored triple-planked, copper-fastened New Zealand yachts built of kauri,” writes Maynard Bray in his description of RAWHITI, the 55' New Zealand–built classic racing cutter that appears on page 80 of this issue. In signature New Zealand style, RAWHITI’s hull is built of three layers of kauri fastened together with copper, a technique that Maynard calls, “one of the most durable of all pre-adhesive construction schemes.” RAWHITI, launched in 1905, has undergone significant restoration but, remarkably, a good deal of her hull is original and she’s still racing.

And then there’s DORIS, also launched in 1905. Tom Jackson describes her in Currents (page 15) as, “at 78' LOA the largest all-wooden hull ever built at Herreshoff Manufacturing Co. (HMCo.)” She is undergoing a thorough reconstruction at Snediker Yacht Restoration in Connecticut and, although her hull is being entirely replaced with new and exceptional wood, fastenings, and metals, her interior will be composed of a good deal of original material.

It’s a remarkable achievement that both yachts are nearing the 120th anniversaries of their launchings. And the fact that they have been preserved or rebuilt to standards as high or higher than original suggests that they have the potential to last for at least as long into the future. With their histories as prologue, we can imagine them still sailing at the age of 200.

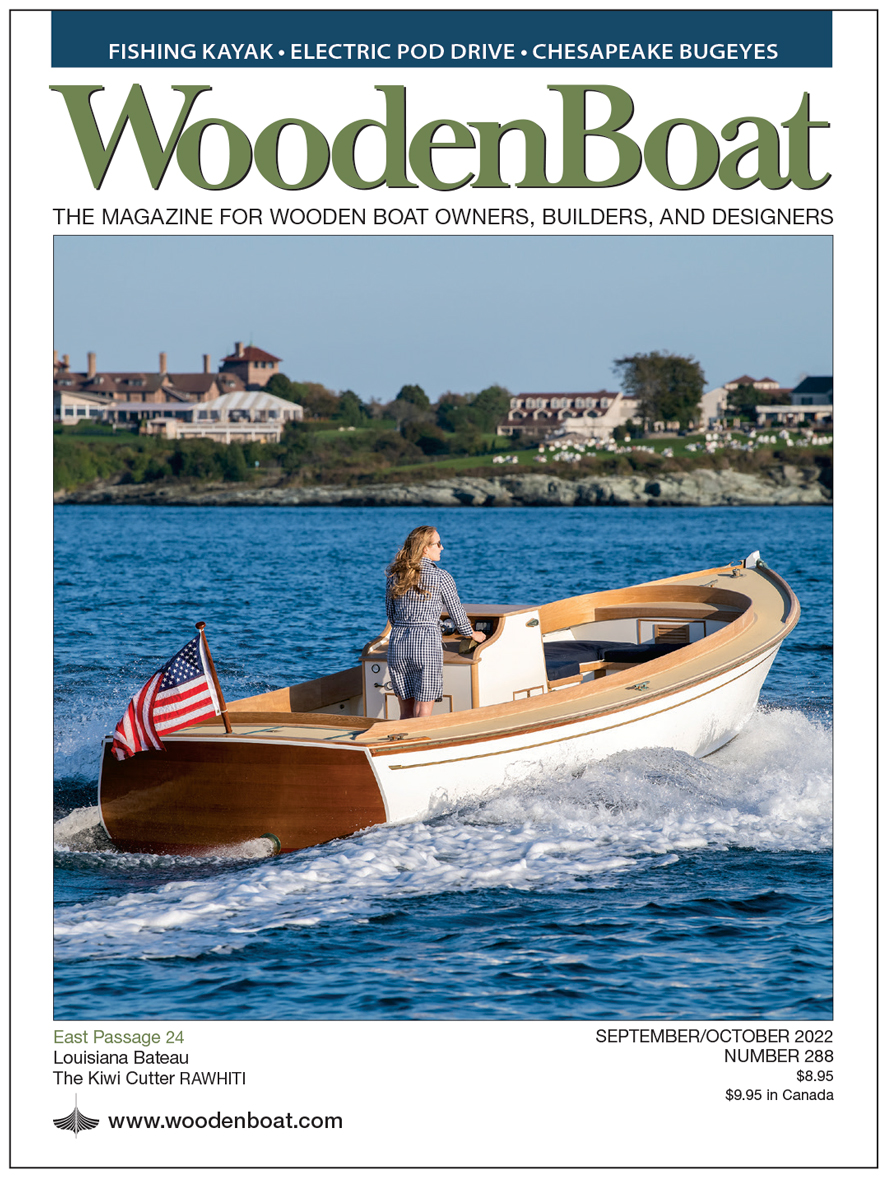

A similarly high standard of construction was applied to the East Passage 24, the beautiful center-console launch on the cover of this issue. She is the product of a collaboration between Carter Richardson, who developed the concept for her and whose company built her, and Walter Ansel, who designed her. Both men brought high standards and deep experience to the boat, which evokes several New England traditions, is built using methods developed over a century ago by Herreshoff, but also employs best current practices in wooden boat building. The boat is double planked, with an inner layer of cedar and an outer layer of mahogany, creating a structure that, with proper care, should be every bit as durable as that of RAWHITI—and, as author-photographer Tyler Fields notes, will minimize trips to the paint booth.

But also consider INTERNATIONAL, a 73' excursion boat built high in the Rocky Mountains in 1927. Proper care and storage have kept her going for nearly a century. Jeremy Masterson writes beginning on page 68 that the boat “was not all that remarkable for her times.” In fact, unlike the aforementioned examples, her construction, although a Herculean task because of the remote building site, was pretty conventional, with western red cedar single-planking, steam-bent white-oak frames, and Douglas-fir structural members, all fastened with steel and iron. A cold, freshwater environment has no doubt contributed to her longevity, but so has a careful and consistent maintenance regimen. Still, as Jeremy notes, “she has weathered windstorms, floods, and snowfalls that collapsed her storage shed roof, threats of forest fires, and government bureaucracy. She has had a couple of minor collisions resulting mostly in propeller damage. She has endured a few periods of less-than-adequate maintenance. By the 1980s, she needed a steward, not just an owner.”

INTERNATIONAL was barely being kept afloat in 1986 when a new owner purchased her and committed to a thorough restoration, accomplished over the course of five years during shoulder seasons, and with the boat operating seasonally all the while. INTERNATIONAL’s steward arrived at just the right time.

And there, in stewardship, lies the common thread among all of these boats, whether they were built exceptionally or conventionally. Visionary ownership keeps them going.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine