Time and Distance

Twenty-three years ago, on a late winter day, I made a day trip to Mount Desert Island, Maine, with Maynard Bray. Maynard, WoodenBoat’s longtime technical editor, knew of a boat there that needed saving, and I was sort of looking, sort of not looking, for a boat. Maynard is an astute matchmaker between boats and people—a penchant that he turned into a regular WoodenBoat department,

Save a Classic (see page 140), that connects boats-in-need with potential owners with the skill, means, or time to love them back to life.

This boat in Mount Desert, I learned, was called a Sound Interclub and was designed by Charles D. Mower. It was partially covered by a weathered canvas tarp. The hull was dried out, and there were some sistered frames. After a few trips to the yard, and after an assessment of the boat’s needs and my time (I was rebuilding the hull of a similar boat then), I passed. Regret ensued, and when the boat was later purchased, moved closer to me, and offered for sale again a few years later, I pounced on it. The following winter and spring I recanvased the deck, patched up a few planks, and went sailing. CAPRICE, as the boat is called, was elegantly simple, original, and mesmerizing to sail (see WB No. 242).

The yachting journalist William Swan, as we learn in Stan Grayson’s article about Charles Mower beginning on page 66, wrote that “one can handle his boat with only thumb and forefinger on the tiller under average conditions.” That line resonated with me, because my natural inclination when sailing CAPRICE was to hold the tiller in just that manner. I nursed the boat along for several years, and when her needs and mine were no longer a match I sold her to a man who commissioned a total rebuild by Reuben Smith’s Tumblehome Boat Shop—an effort that preceded Reuben’s restorations of several more Sound Interclubs and

a revival of the fleet.

Despite my deep admiration for that boat, I knew woefully little about Mower. I knew that he’d practiced for a spell in the Boston area and built a robust clientele when he moved to New York. I knew he’d been design editor for The Rudder magazine. But I did not know, until I read Stan’s article, that he was born in Lynn, Massachusetts, not far from my childhood home on that state’s North Shore. If the timing had worked out a little differently, I might have known him as a casual local acquaintance. Instead, I know him as a legend.

The breadth and ubiquity of Mower’s output had a monumental influence on yacht design not only in the Boston and New York areas but also across the country and even worldwide. The stunning 46' yawl shown on page 69 was for a client in Seattle. The Express Cruiser on page 70 was for an owner in Argentina. While researching the illustration for this article, I discovered a Mower boat designed for an owner in Vyborg—a former Finnish town captured by the Soviet Union in World War II, through which I passed in a bus, wide-eyed, on a trip from Finland to St. Peterburg, Russia, in 2003, researching the worldwide phenomenon of replica-ship construction (see WB Nos. 172–175). I was stunned to learn that C.D. Mower had a connection to this place that, until a decade before my trip, had been walled off from the West. On that trip to Russia, I also connected with two Russian friends who had been students at The Apprenticeshop in Rockland, Maine, and, in a profound melding of diplomacy and apprenticeship, had gone on to establish similar efforts on Russia’s Neva River.

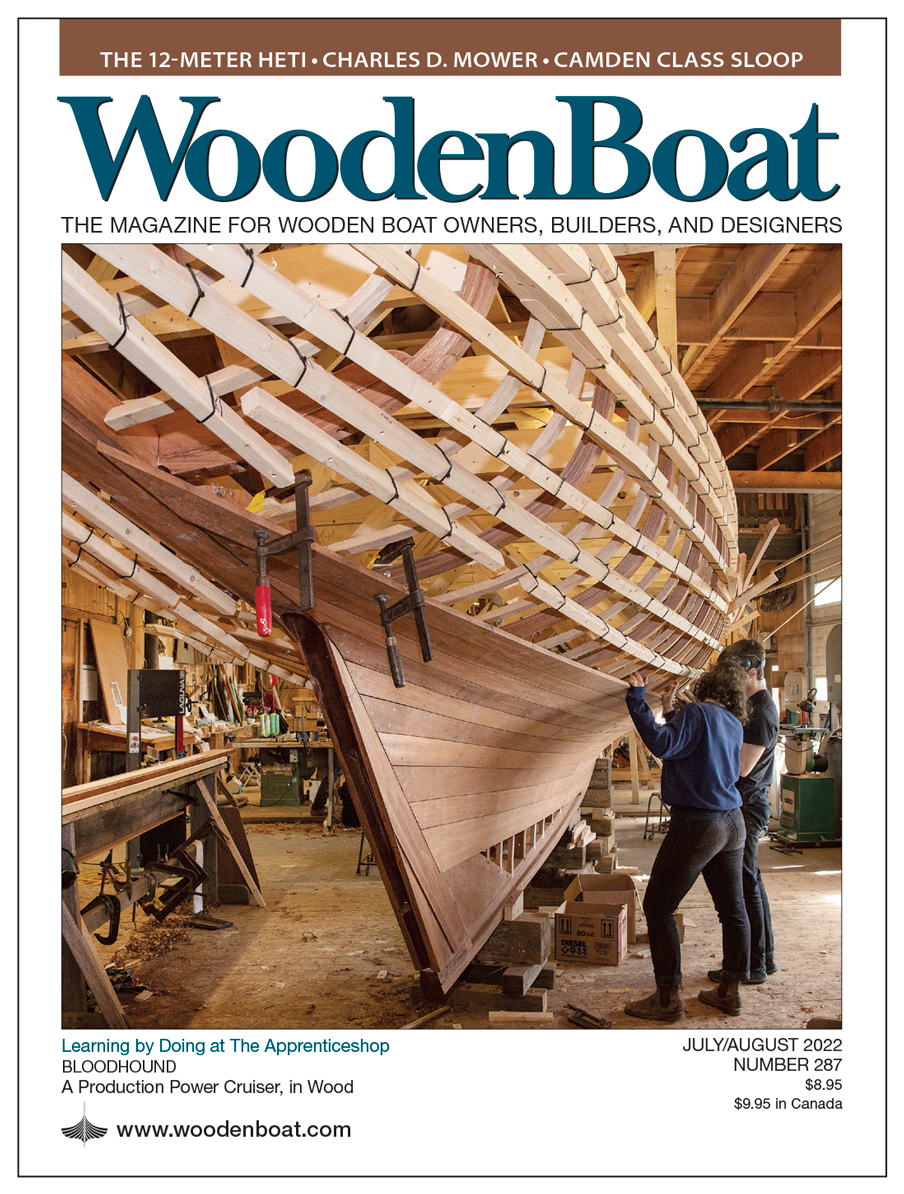

Lance Lee, who founded The Apprenticeshop (page 34, and cover image), introduced me, 30 years ago, to Bob Gilbert, owner of the magnificent Fife cutter BLOODHOUND. Through that connection, I subsequently met Bob and sailed in BLOODHOUND in San Diego for an article in WB No. 128. Through some further twists of fate and connection, BLOODHOUND has moved to the Northeast and spent last winter in Maine. In planning a new article about her, I learned that Scott Kennedy, who has been associated with WoodenBoat as an artist and illustrator for many years, has family connections to the original BLOODHOUND’s original owner, the Scottish Marquess of Ailsa, and that the plans to build a copy of her were discovered, carefully guarded, in his ancestral family’s castle. Scott was a friend of Bob and regular crew on the second BLOODHOUND, which could be built only after Bob earned the trust of the then-current Marquess of Ailsa. He describes these connections beginning on page 56, illustrating yet another example of the power of wooden boats to breach castle walls and connect people across distance and time.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine