The Once and Future Multihull

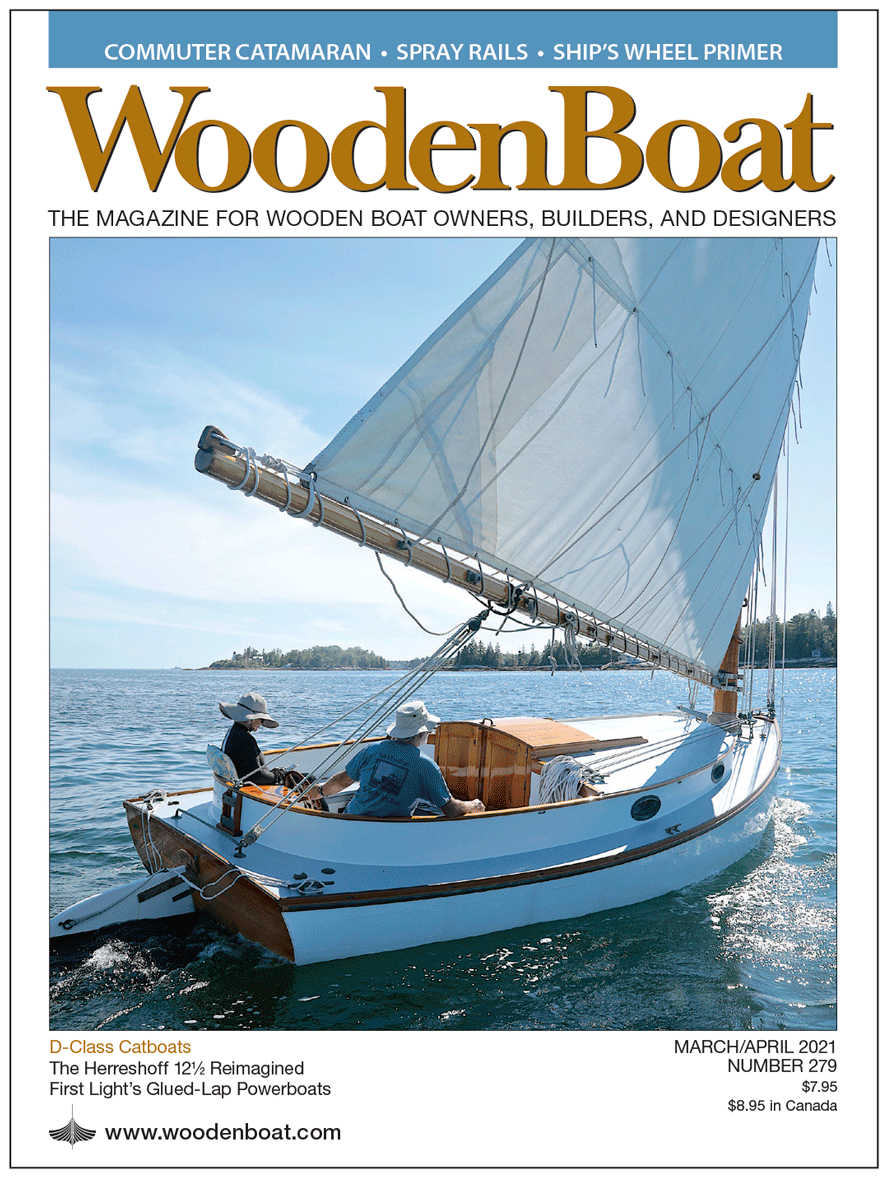

In his article beginning on page 64, Benjamin Neal describes the power catamaran FLOW as “an experimental platform for advancing conversations about energy efficiency.” He continues: “she represents a bold step toward a new mode that prioritizes low power….”

Indeed, with her two long, narrow hulls reaching out from her passenger pod, FLOW resembles something between a spaceship and a water bug. She was designed by the Seattle-based multihull designer Kurt Hughes, whose portfolio includes a vast array of catamarans for both sail and power. Her concept is not without precedent. For example, a decade or so ago Russell Brown, the Port Townsend, Washington–based proa expert who is something of a legend in the world of wood-composite boatbuilding, repurposed the hulls of an old Tornado-class catamaran for outboard power. He slung a passenger pod between the hulls, mounted a modest outboard motor on the reconfigured boat, and used her as a fast and economical commuter on Puget Sound for many years. GRASSHOPPER, as she was called, was locally famous. Conceptually, she is a miniature and less complex version of FLOW.

FLOW’s construction was a joint effort between her owners, Earl and Bonnie MacKenzie, and Matthew Reynolds of Sarasota, Florida. Ben calls her “futuristic,” and I agree: she is a rarity in Maine waters. In fact, I recall, years ago a Maine-based boating magazine presenting a catamaran lobsterboat, tongue-in-cheek, as an advancement of the traditional Maine lobsterboat design. But rising fuel prices and the environmental impact of burning fossil fuels since then have brought conversations of fuel efficiency into sharper focus. A workboat modeled on the concept of FLOW now doesn’t feel like satire—although there are barriers to making this idea practical.

Ben notes that one pays a performance penalty for excessive weight, and carrying capacity is a big part of the function of a lobsterboat. Extreme weather conditions can also affect the performance and maneuverability of a powered catamaran such as FLOW.

On the other hand, the previous issue of WoodenBoat (No. 277) included David Payne’s article on the traditional sailing canoes of Papua New Guinea (PNG). In that article, David reminds us that the idea of multihulls for voyaging, cargo-carrying, and fishing has been proven through millennia. He presented a gallery of immensely sophisticated outrigger canoes that had evolved for various purposes—voyaging, fishing, cargo transport, and even war. Efficiency was critical to their operation, not because of a shortage of fuel but because of a need to squeeze maximum performance out of abundant wind. These boats are as sensitive to weight and balance as FLOW, but the ancient sailors who developed them learned to harness this sensitivity for steering and speed. “Steering,” David wrote, “is the essence of simplicity: by raising and lowering the rudder blade aft, the balance between center of effort and center of lateral resistance is manipulated. Pushing the big blade down drags the hull balance point aft, causing the craft to bear away; raising the blade up brings the craft up toward the wind direction.”

It’s interesting to compare this description with Ben’s account of how FLOW handles: “she moves nimbly from low to high speed without the ‘hump’ of a planing hull, and without throwing spray onto passengers. She accelerates easily, can pivot in her own length, and has a soft ride.”

The PNG canoes, like FLOW, look futuristic, but their origins date back at least 5,000 years. While FLOW is indeed a visionary boat, her concept draws on ancient genius.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine