Beneath the Surface

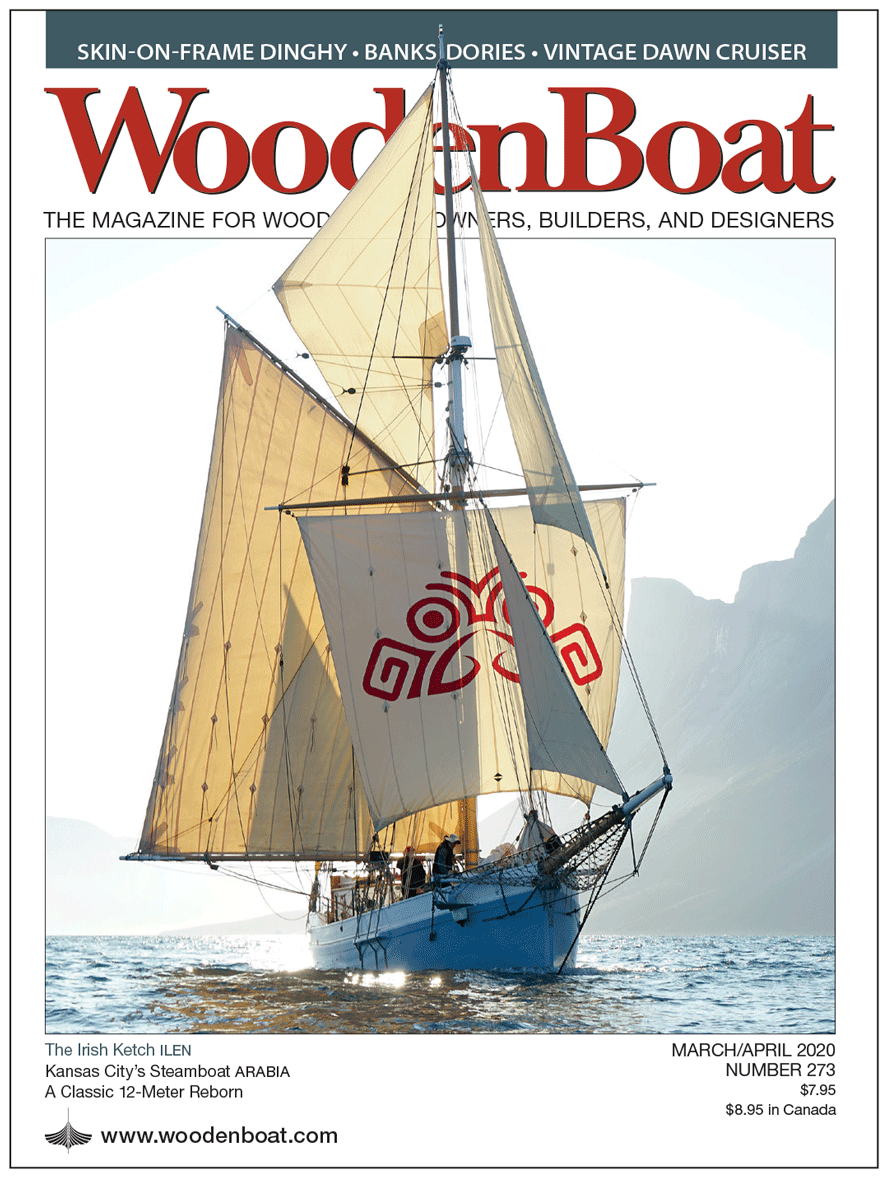

Gary MacMahon’s image of the tidy Irish cargo ketch ILEN on the cover of this issue belies the fact that, more than 30 years ago, ILEN was languishing in the Falkland islands. As we learn in Arista Holden’s article beginning on page 48, MacMahon engineered the improbable repatriation of ILEN to Ireland, and her subsequent multi-year restoration. After relaunching, she voyaged to western Greenland—the location of the cover photograph.

And then there’s JENETTA (page 78). Ten years ago, she was lying on the bottom of a Canadian lake. She was in such a weakened state that when raised to the surface, she broke into three pieces. Those pieces were shipped to the Robbe & Berking boatyard in Flensburg, Germany (see WB No. 258), which eventually took on a thorough reconstruction of the boat.

It’s not the first time we’ve presented the restoration or reconstruction of a sunken and seemingly doomed boat. I’m reminded of the ketch YUKON in WB No. 220. Her owner, David Nash, acquired her when she was sitting on the bottom of a Danish harbor. At the conclusion of his multiyear restoration, he sailed her to Tasmania, where he and his wife, Ea, operate her as a charter boat. I’m reminded, too, of the Colin Archer ketch CHRISTIANIA (see WB No. 160), which sank in 1,640' of water in the late 1990s. The crew survived. Incredibly, driven by the boat’s historic value, CHRISTIANIA was raised and restored, and continues today as a voyaging yacht.

The sunken steamboat ARABIA, however, is a rarity among wrecks that have been raised from the bottom and presented on these pages. Beginning on page 68 of this issue, Tom Varner tells of how this 171' paddlewheeler sank in the Missouri River in 1856. More than 130 years later, she was discovered 45' beneath the surface…of a cornfield. The river had meandered from the wreck site, encasing it in silt and capping it in topsoil.

ARABIA’s salvors began their mission planning to sell what they recovered. But ARABIA’s treasures moved them beyond the idea of instant profit. They instead kept the collection intact and became collectors, preservationists, and curators. They created a unique museum offering a rare window into life on the American frontier in the mid-1800s.

One need not raise a boat from the bottom of the sea, or a cornfield, to find such treasures—such rare windows into the past. Consider, for example, the Bud McIntosh–designed and –built sloop GO GO GIRL (page 58), found wrapped in tarps and brought back from the brink by Paul Rollins, who had a singular connection to her history. Or the 48' Dawn Cruiser WIDGEON, a rare survivor kept in service for the past 40 years by her dedicated owner.

In his article on GO GO GIRL, Randall Peffer quotes Bud McIntosh recalling his career building wooden boats as an “emotional experience almost unique in this modern world.” As the world grows more “modern,” those words grow more relevant, and they apply as well to the restoration, use, and appreciation of historic boats, yachts, and vessels. The opportunities to own and care for them lie all about. Some of these opportunities lie waiting on the surface, in brokerage and classified advertisements. And some, squirreled away in barns or hidden under tarps, lie just beneath it.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine