Bahamian Sloops—Part I

Class A sloops racing in 2005—photo by Delfine (Reuel’s Angel #1).

I first sailed to the Bahamas in March/April of 1981. I had sailed my cutter FISHERS HORNPIPE from California, via the Panama Canal. I immediately fell in love with the Bahamas, and have been visiting them every opportunity since. That first trip, we were in George Town, Great Exuma for the Family Island Regatta—native sloop races.

The Regatta in Great Exuma is in April—late for me to be in the Bahamas, as I usually try to make my annual migratory trip to Maine before Mayday. Hence I have only been to four Regattas.

The races take place in Elizabeth Harbor, between Great Exuma and Stocking Island. The harbor is large and shallow, but the sloops have full keels, with drafts of around four feet maximum—Class A sloops are permitted a midships keel depth of 24”—which I assume to mean below the curve of the bilge.

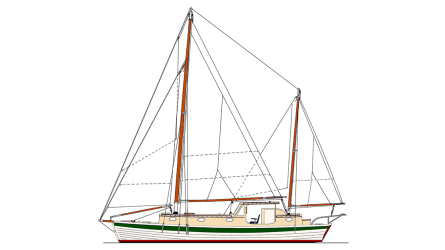

There are three classes of sloops, increasing in size from Dinghies; Class B sloops; and Class A sloops. Class A sloops must be no longer than 28′ 3″ between perpendiculars, and between 8′ and 10′ 6″ beam. The hulls and masts must be made of wood, though fiberglass is allowed as a deck covering (many of the newer sloops are cold-molded). The boats cannot have bowsprits, spreaders, winches, or instruments. Sails must be cotton, with no wire luff ropes. Rigs must be traditional Bahamian sloop: Small overlapping jibs tacked to the stem-head; and large rounded mains’l headboards (essentially single-halyard gaffs). Up to three “pry boards” are allowed—planks held to the deck by large staples, run out to windward to seat human ballast (as used also by Chesapeake Bay sailing log canoes). The sloops must be Bahamian designed, built, owned and skippered. They have inside ballast, lovely sweeping sheers, and wineglass hull shapes. Rudders are transom-hung, and tillers pass through a slot in the upper transom. Transoms are raked, wineglass-shaped, and usually have a distinctive color-stripe across them near the top.

A Class A sloop with maximum human ballast on her “pry boards”.

The boats are lined up at anchor before the start of each race, and start by weighing anchor hand-over-hand as fast as possible. All except the lead boat must start on the starboard tack. There are buoys marking the race course, which includes various points of sail. The races are action-packed and exciting to watch! In my opinion, they are much more fun than any other yacht races I have ever been to, including the America’s Cup race in which AUSTRALIA II took our cup away for the first time.

Howland Bottomley, Commodore Emeritus of the Regatta, wrote a “brief history” which you can read on the Regatta’s website (www.nationalfamilyislandregatta.com). Following is the first paragraph:

“By the early 1950’s, working sail was fast disappearing from this part of the world. The Grand Banks fishing schooner was all but gone, the Chesapeake oyster dreggers were no longer being replaced as they were laid up, and the many vessels still working under canvas in the Bahamas had an uncertain future. In 1954 a small group of Bahamian and American yachtsmen conceived the idea of holding a regatta for the Bahamian working sailing craft.”

Hence the Regatta was conceived to “offer a fine opportunity for Bahamian sailors to all gather in one place, have some sport, and a chance for cruising yachtsmen to witness one of the last working sailing fleets in action and at the same time introduce them to the magnificent cruising grounds here in The Bahamas…. So it was in the late April 1954 nearly 70 Bahamian sloops, schooners, and dinghies gathered in Elizabeth Harbour for three days of racing.”

And thus the Family Island Regatta was born.

The Regatta evolved over the many years since 1954 into what it is today. Strict (but not too strict) rules govern the boats. My friend naval architect Art Paine is instrumental in planning and judging the races, and in helping to formulate those rules. Art (Chuck Paine’s twin brother) is an ardent supporter of the regattas, and creates beautiful paintings of the sloops.

The beautiful miniature island city of George Town—hub of the southern Bahamas—hosts the Regatta each year, and the parties—music, dancing, drinking and racing are epic in scope. Plywood shacks pop up like mushrooms all over the waterfront (really there is nothing but waterfront), with compact kitchens, bars, tables & chairs. Bahamian food is served up hot and inexpensive: dishes like cracked conch, spiny crayfish, conch fritters, baked macaroni & cheese, roast pig, fried or grilled dolphin (mahi-mahi—not Flipper), grouper, rice & peas, conch salad, and more. Loud speakers are placed strategically, and soca, calypso, and Junkanoo tunes, along with race results, are blasted at ear-damage levels. Caribbean dark rum and Kalik (local beer), flow in vast quantities, and the sweet smell of burning herb (splif) can be smelled everywhere. Dancing goes on late into the tropical night. Hangovers can be brutal.

Despite what elsewhere would be a ripe environment for trouble; anger or confrontation is very rare, and crime is virtually nonexistent (at least in my experience). Good fellowship and happiness abound for days!

Other Bahamian islands have picked up the original theme, and now regattas can be attended at their various locations and times—I regret I have never been to any of them. I think these “out island” regattas include Cat Island and Long Island.

Over the years, a handful of Class A sloops have dominated the winning position, including: LADY MURIEL; TIDA WAVE; RUPERTS LEGEND; RUNNING TIDE; AND RED STRIPE. Following are some of my photos of these and other spectacular Class A sloops:

RED STRIPE and RUNNING TIDE at the windward mark.

RUNNING TIDE getting under way, showing her twin pry boards.

ABACO RAGE getting under way.

NEW JIFFY.

TIDA WAVE.

TIDA WAVE in 2012, moored at Staniel Cay.

In the above photo of TIDA WAVE you can see the deck staples under which the inboard ends of the pry boards are inserted. When tacking, the boards are rapidly shifted across the deck to the new windward side, and the “rail meat” crew clamber into place as the wind fills on the new tack.

In a later blog I will discuss the state of traditional working Bahamian sloops in modern times.

8/18/2014, Appleton, Maine