Kemp’s Instructions for Setting Jackyard Topsails

Taming the tiger

Taming the tiger

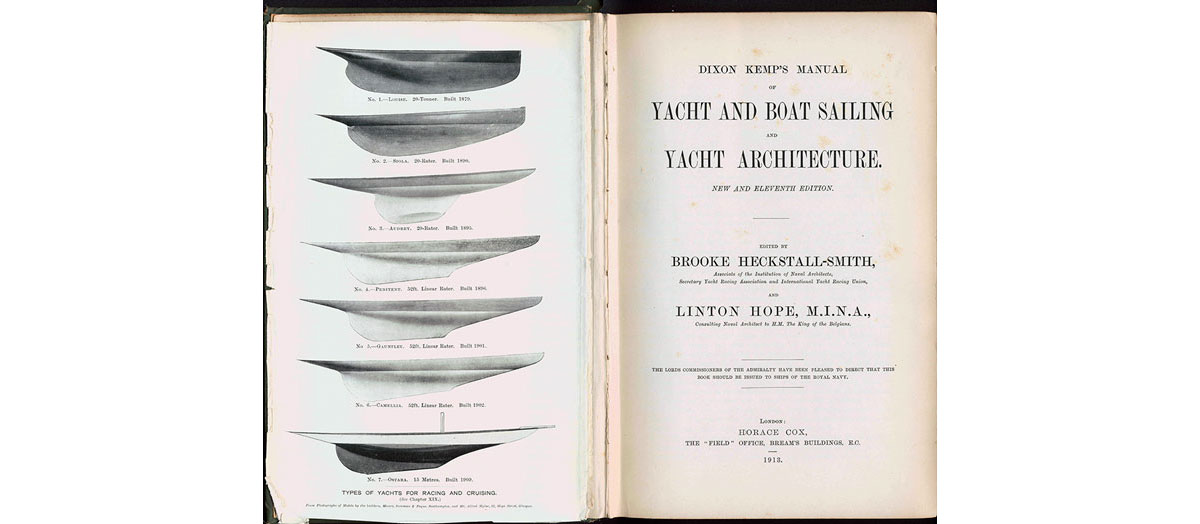

Title Page to Dixon Kemp’s Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing and Yacht Architecture (View pdf).

Pages from Dixon Kemp’s Manual of Yacht and Boat Sailing, in the PDF above, describe the mind-numbing details of setting, sheeting, and taking in a jackyard topsail on a large racing schooner.

Kemp’s detailed process is hard to comprehend without a topsail yard in hand. The text includes terms like “passing the weather earing” that may have no apparent counterpart in boats today, thus increasing the confusion for a modern sailor. It is not all ancient history though, you will recognize the still useful anchor knot in Figure 33. Do you know what it means to “bowse down the tack to the last inch to take all the render out of the halyards”?

In WoodenBoat No. 131 (page 58), Pauline Carr wrote about sailing her cutter CURLEW, carrying a jackyard topsail. Perhaps the finest high-latitude sailors of our age, Pauline and Tim Carr, describe how they “shift gears” using their jackyard topsail in light airs. Kathy Bray translated Tim’s sketches of the rigging into precise drawings for the article.

Pauline Carr warns, in a way that suggests personal experience, of the ghastly mistake of flicking the outer sheet around the end of the gaff, effectively tying a knot at the end of the gaff, and of “the ensuing blushes and curses” on deck when this disaster strikes. The topsail won’t come down, remains tied aloft, set and drawing in increasing wind! Kemp anticipated this struggle in his instructions above, describing the importance “of hoisting away on all” or “otherwise, if the sail blows about, the sheet may get a turn round the gaff end.” He offered a solution to this unhappy turn of events: send a man aloft to address the problem! and I think Kemp means to send a man out to the end of the gaff… while set… in a raising breeze… to flick the loaded sheet free of the peak of the gaff! An alarming vision to contemplate, and reason enough to leave the jackyards at home, except in light air.

Pauline reports that her husband, Tim, the consummate high-latitude sailor, usually sets CURLEW’s jackyard topsail on his own, and that it is a fun thing to do. CURLEW’s jackyard topsail is 170 square feet of sail laced onto two Douglas-fir spars, one is 16′ long and the other one is 10′ long.

So setting a jackyard topsail is still being done by some of the best sailors in the world.

Kemp warns that this sail requires a master hand’s constant attention, much as a physician would watch an invalid. “A man must take an interest in the most minute details of his craft.” His final word on sheeting, “The big jackyarder is the first sail to lift, owing to the angle at which it lies to the wind, and too much care and attention cannot be given to it in order to keep it in its place, and so make it effective instead of a hindrance when sailing on a wind.”

Captain Jim Thom, captain of the 19-metre MARIQUITA, explained how to handle her sails in an article in WoodenBoat No.185, (July/August 2005). MARIQUITA, 95′ on deck, has topsail yards 35′ long, and she requires 30 crew. She was built in 1911 by William Fife & Son in Fairlie, Scotland. Starting on page 64, Maynard Bray introduces MARIQUITA in an article featuring photographs by Benjamin Mendlowitz. Thom’s article immediately follows Bray’s piece.

Kemp mentions that sailors formerly lowered the topsail to leeward of the mainsail but he (in 1913) advocates the practice to lower the topsail to windward of the main. He would send two men aloft to move the tack of the topsail to windward and bring the yards and sail down in the belly of the main.

Capt. Thom brings his topsail down to leeward of the main and explains why in this article. He replies to Kemp’s idea to send two men aloft to dowse the topsail: “In the good old days, the mastheadman, who lived aloft would lash the heel of the yard and lace the luff to the mast.” (Hence, his instructions above to send a man aloft to cast off the lacing.) Thom continues, “But the rising cost of replacing broken mastheadmen means that we haven't revived this traditional task. It also means we can bring the sail down in a hurry without having to send someone aloft.” He adds that “as you might imagine, it murders the varnish on the spars as you drag them over the galvanized wire peak spans.”

He recommends that you raise the sail when the wind is light, and carry it until the race is over. Then he douses it “peacefully in an orderly manner at the end of the day” by heaving to, head-to-wind with a backed jib, thereby “reducing friction for the crew.”

You can find a little more about Jim Thom by watching this two-part interview on Classic Yacht TV as Jim finishes his nine years as captain of MARIQUITA. Link to Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

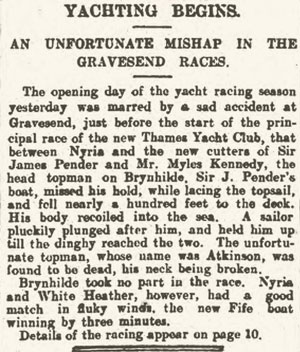

An Unfortunate Accident

From newspaperarchive.com

The London Standard, of Thursday, May 23, 1907, reported on the death of a mastheadman tending the jackyard topsail. Just before the first race of the season held by the New Thames Yacht Club at Gravesend, Mr. Atkinson, the head topman of the 23-meter BRYNHILDE, “missed his hold, while lacing the topsail, and fell nearly a 100 feet to the deck. His body recoiled into the sea”. BRYNHILDE took no part in the race that day.

Charles Pears, the British illustrator, was on the race and drew a sketch of the three 23-meter yachts being towed out to the race course, and reported seeing BRYNHILDE towing back to port with her racing colors struck.