Beach Pea

Five years ago, I needed a new dinghy to commute to a new mooring a half-mile or so from the dinghy dock. My family had outgrown our pint-sized tender, and there was also too much open water to cross in that little boat. My first impulse was a peapod. These double-ended classic Maine workboats are legendary for their nimbleness, versatility, and load-carrying ability. Several of my friends had used them as tenders, and raved about them. And so I began scouring the local advertisements for the right boat.

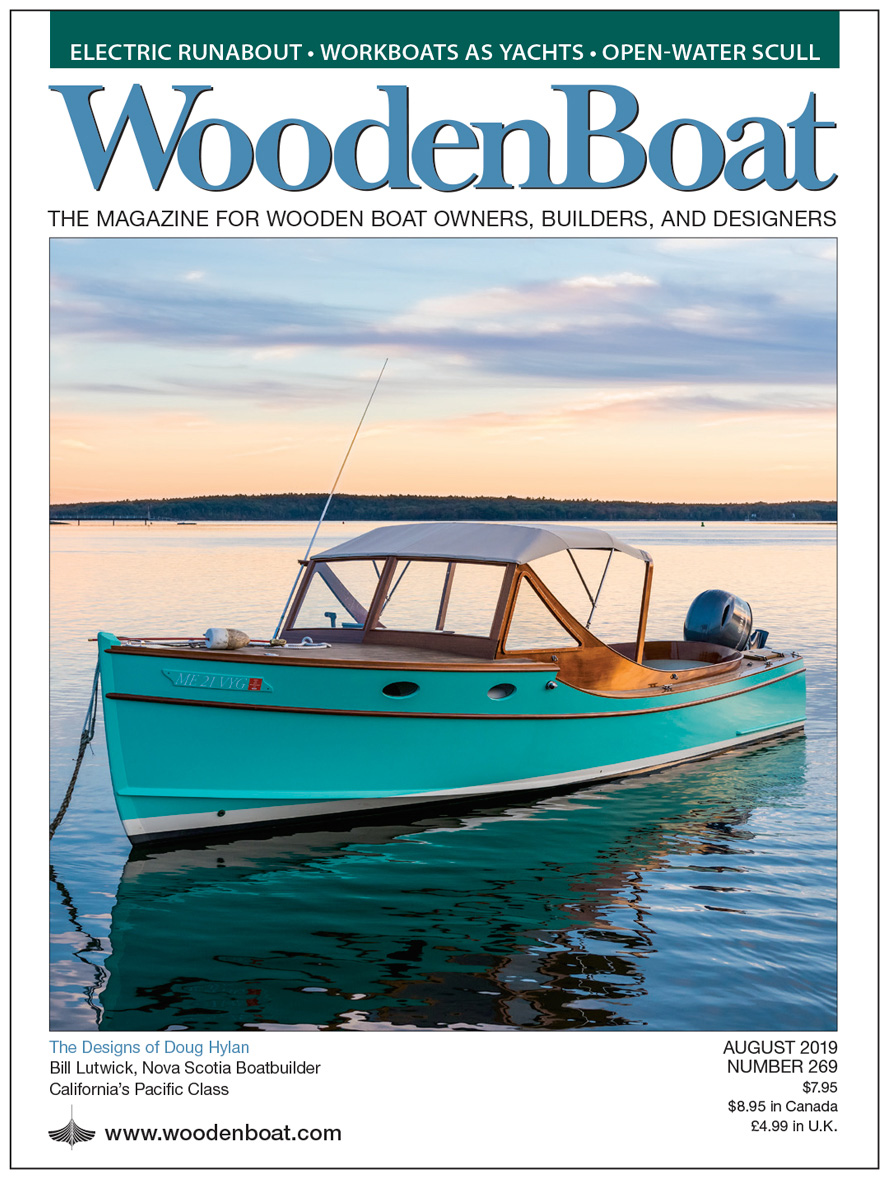

As luck would have it, just as I began my search there appeared a listing for a Beach Pea, which is designer Doug Hylan’s interpretation of the traditional workboat—but updated for recreational use and construction in glued-lapstrake plywood. That’s Hylan’s stock-in-trade, as we learn in the article about him beginning on page 52: He bases many of his designs on historic workboats, altering them for pleasure use. In 1996–97, WoodenBoat published a three-part series on building the Beach Pea (see WB Nos 133–135), so I knew something about the boat. Since purchasing mine, however, I continue to be amazed at the genius of this design—not so much the physical details, but rather the stuff you don’t see.

Take, for example, the boat’s longitudinal balance. Beach Pea is a true double-ender, meaning the forward sections are identical to the aft ones. With a single person rowing, the designed bow points forward. With two people aboard, the oarsman moves aft one thwart, spins around 180 degrees, and rows the boat with the designed stern facing forward, with the passenger sitting in the designed bow—which is now, functionally, the stern. Some boats require trim ballast to carry a passenger, but not so the Beach Pea.

My Beach Pea does not carry a sailing rig, but I tried out Hylan’s a few years ago for a photo shoot. During that session, the beauty of a carefully balanced rig revealed itself in the boat’s handling qualities: It has no rudder, and is instead meant to be steered by shifting both crew weight and the position of the centerboard. One can also use a steering oar, but I was astounded at how easy it was to steer this boat straight without one.

The boat rows beautifully. Although the half-mile crossing became effortless, I would occasionally hear incredulous comments that I wasn’t using an outboard-powered inflatable boat for my trips to the mooring. I would certainly have grown weary of the journey in a lesser boat than the Beach Pea, but the fact is that it was the Beach Pea’s handling qualities—its light weight, its glide between strokes, its straight tracking, and its carefully considered geometry—and not my rowing skill, that made the journey fun and easy.

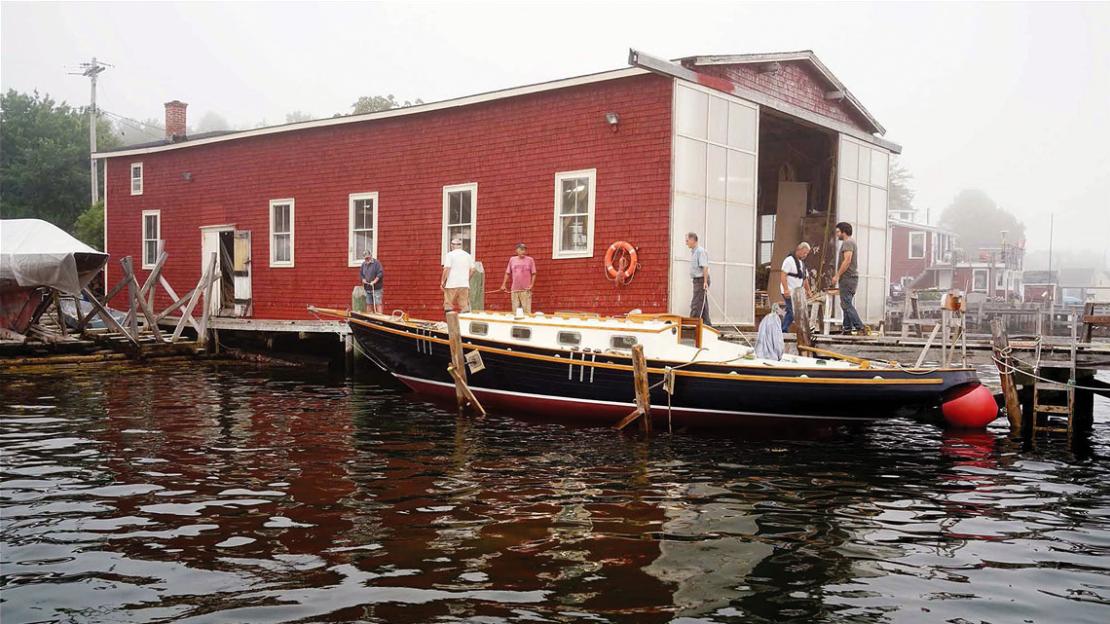

I don’t know who built my Beach Pea; I bought her from a man who bought her from the builder. But I do know that her shape and details are tight to the plans. This, I am sure, is due in part to the competence of the unknown amateur builder. But it is also due to the principles of the designer. As his business partner, Ellery Brown, has said about Hylan, “If a boat was launched with his name on it, whether it came out his own shop on Benjamin River or out of a garage in Detroit, whether it was built by a master craftsman or a rote amateur, he wanted to do everything he could to ensure it was structurally and aesthetically correct, and he would do that from behind a computer, rather than a table saw. He would research and consider, draft and adjust every detail before he pressed print.”

My Beach Pea is but a small illustration of this. In our profile of Hylan, we are treated to a gallery of his designs that prove, again and again, that a focus on historical good looks and functionality, rather than on flashy trends, speed, and power, yields timeless, evolved, and satisfying designs that work.

Editor of WoodenBoat Magazine