Bahamian Sloops—Part II

In my last blog I wrote about Bahamian sloops as Regatta race boats. The Regatta, initiated in the mid-1950s, did wonders for preserving the sloops—but it also transformed them from humble, pragmatic work boats into hotrod racing machines. No Bahamian fisherman would be likely to take his Regatta boat out to the fishing grounds.

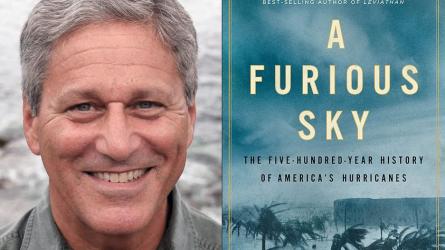

A Bahamian Fishing Sloop beached for painting in Rolleville, Great Exuma, in 1987. In the foreground is a class of school children on a field trip.

In this blog, I will write about the Bahamian sloops that survived as working fishermen, more or less.

When I first sailed to the Bahamas in early 1981, I had never heard of a “Bahamian Sloop” and was unaware that it was a well-known and highly regarded historic type. In the lobby of the Peace and Plenty Hotel in George Town, Great Exuma, there is a beautiful and accurate painting showing traditional Bahamian work boats. I may have seen a sloop depicted there before even seeing one in real life (shortly thereafter). They have become scarce—an endangered species—so to speak.

In the 1981 Family Island Regatta I had the great pleasure of racing as crew on the Class A sloop DIAMOND CUTTER out of Nassau, New Providence. She was owned by a white Bahamian, and had a mostly white crew (his friends and neighbors). Her mast was not as outrageously tall as those in the other racing sloops, and after a good start weighing anchor (less windage), we got our butts kicked—came in last! But the race was a thrilling experience for me none the less—I had a blast! And the parties afterward… well I already told you in the last blog.

Shortly after that time I purchased my first copy of Howard Chapelle’s AMERICAN SMALL SAILING CRAFT (the first of two, as I completely wore it out and had to buy a second copy), and first read about the Bahamian Sloops there, from a historical perspective. I became a fan, and afterward paid attention to learn more about the sloops, their history, and their condition and use in the present.

I took the photo above when cruising the Exumas in my cat schooner TERESA in 1987. I had a girlfriend with me on that voyage (Robin Nagel), who was an anthropology student interested in native Bahamians, and we followed a lead to visit Reverend Granville Hart in Rolleville, near the north end of Great Exuma. He was reputed to be restoring a traditional Bahamian fisherman, and our mutual interests (maritime history and anthropology) drew us to seek him out.

The Reverend Granville Hart, shown with the fishing sloop he was restoring.

We spent a couple of hours exploring Rolleville’s architecture, talking, looking at the sloop, and meeting local men, women and children.

Reverend Hart (center) and anthropology student Robin Nagel (right), talking with the reverend’s wife (not visible to right).

The reverend intended to put the finished sloop back in service for the job she was intended to do—fishing. He told us that sloops like her had become extremely rare, and he was determined to rescue this one and restore her—not as a museum piece—but as a working fisherman.

* * * * *

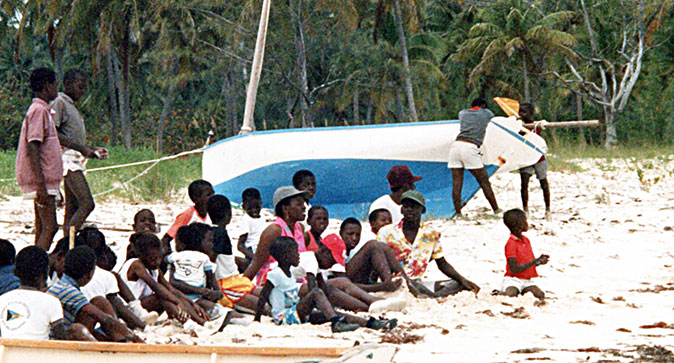

On my first cruise to the Bahamas, or perhaps my second (both in my cutter FISHERS HORNPIPE), I met an elderly man in Nassau who had similarly restored a traditional fishing sloop, and used her to take tourists out for a sail for hire. He was glad to have her earn her way in this unorthodox fashion, as long as the money coming in kept her (and him) alive.

An “in service” traditional Bahamian fishing sloop in Nassau in the early 1980s.

Sloop master builder Leroi Bannister

I continued searching out—and photographing—Bahamian sloops whenever I could find them. All too often they were wrecks. In my Virginia pilot schooner LEOPARD, I met Leroi Bannister at Lisbon Creek, Andros, after exploring the South Bight (a 23-mile tidal jungle passage through the island, of very shallow creeks and “blue holes”). Mr. Bannister had been a master builder of Bahamian sloops—both fishermen and Regatta racers—and was a legend in his time. It was a great honor to meet him and visit with him before his death in 2008.

Lisbon Creek, Andros, and the wreck of a Bahamian fishing sloop.

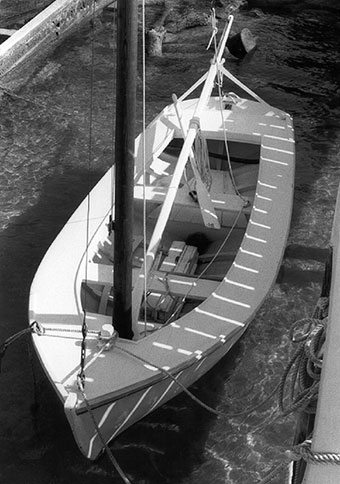

A Bahamian fishing sloop in Elbow Cay, photographed about 1996 by my crewmember Lucy Trinder.

The Abacos—islands in the northern Bahamas—are home to the Albury family as well as a few other builders of Bahamian craft. These are white Bahamians who immigrated to the islands during the American Revolution—whole families of Tories driven out of the colonies because of their affiliation with England. Many settled in the Abacos, including Man-O-War Cay, where they set up boatyards, some of which are still active today. The quality of their workmanship is world-renown, and they still build a few boats in wood, although they also build in fiberglass.

On a trip to Cat Island in my ketch T’IEN HOU in 2002, I anchored in Bennet’s Creek—an extremely narrow and shallow estuary—and photographed the following sloop in her final resting place.

Wreck of a traditional fishing sloop in Bennet’s Creek, Cat Island.

Many of the later fishing sloops appear to be gaff-rigged, although the best-known traditional rig is Marconi sloop, characterized by a narrow jib and large, often “S” shaped headboard or gaff.

Bahamian dinghy showing the typical method of reefing.

The classic Bahamian Dinghies (documented by Chapelle and other historians) were often rigged as catboats—with the mast stepped far forward, and no jib. All the sloops had very simple and pragmatic methods of reefing. One was a “tricing line”—a continuous loop or bight of line which originates near the mast head, passes under the sail (but not the boom) returns aloft with a fall down to the deck. The mains’ls are noted for having a large, baggy foot, which hangs well below the boom so far as to drag on the deck in many instances. By hauling on the tricing line, this huge bag of sail is “scandalized” by pulling it up above the boom in a bundle. Hence the sail is reefed up—not down as are modern sails. Tricing lines can be traced to traditional fishermen and pilot boats of the British Isles.

The other method of reefing involves the simple expedient of lowering the sail the desired amount, bundling a portion of it just forward of the clew, and tying it off to the boom.

While sailing on the Bahama Banks east of the Exuma chain of islands, I have often seen native sloops from a distance. Some must work in sponging; some in trapping; some gathering conch, crab and crayfish (lobster); some carrying cargo; and some fishing with hand lines. I have never been close enough to one to ask.

Native Bahamian fisherman with dinghy and what appear to be traps, on the Bahama Banks.

Native sloop on the Banks with a gaff rig.

A native sloop on the Banks with mains’l made from recycled advertisements—possibly a Haitian vessel.

The above three sloops are gaff rigged (the third may be considered Gunter-rigged), which seems common now for larger (over 30 feet) fishing, sponging, trapping and inter-island cargo sloops. Many sloops now have diesel engines, and in some, the sails become either sail-assist, vestigial, or emergency back-up. Many native schooners are missing their mainmasts, which have been replaced by machinery.

The working Bahamian Sloop today is a rare sight… but I am glad there are any left to see at all. The Regattas have been a wonderful way to keep traditional craft alive, and I desperately want to see at least one more before I, too, am gone. And of course I will continue watching out for sloops still at work under sail.

9/10/2014, Appleton, Maine